Kernel Magazine Issue 5 is out! The US Open starts this week! What a perfect time to release Arushi Bandi’s excellent essay from Kernel 5 on electronic line-calling in tennis! To see this in print, get your copy of the magazine now!

—Jacob Sujin Kuppermann

P.S.: Jess Dai, Humphrey Obuobi, and I are going to be at Bathers Library’s Summer Symposium in Oakland this Sunday talking about the potentials of liberatory & communal technology (Rejected title: It’s Time To Build (Leftistly)); see you there! (Immediately afterwards, Kernel Mag Alum Adora Svitak is giving a talk on heteropessimism, if you’re into that sort of thing!)

📏 When machines start calling the shots

By Arushi Bandi

Edited by Jacob Sujin Kuppermann

“Are you sure it’s out?”

In tennis, if the ball touches any part of the line, it’s called in; otherwise, it’s out. Growing up playing competitive tennis, we made our own line calls. On close calls, the rule of thumb went: if you’re not sure, it’s in. One might assume that teenagers self-refereeing would lead to all sorts of petty disputes—and when this did happen, the nearest figure of authority was called upon, usually a tournament director or coach. But what I remember most about this system is the additional merit it added to the game, shelved alongside perseverance, conviction, and craft: a sense of principle. Calling a close ball out cheapened a win, as much as it was also a part of the game. (This pattern persists at the highest levels of the sport, where players stand by silently as bad calls or misunderstandings tip into their favor). At all levels of the game, line calls in tennis teach us an important lesson: that how a rule is enforced is of as much significance as the rule itself.

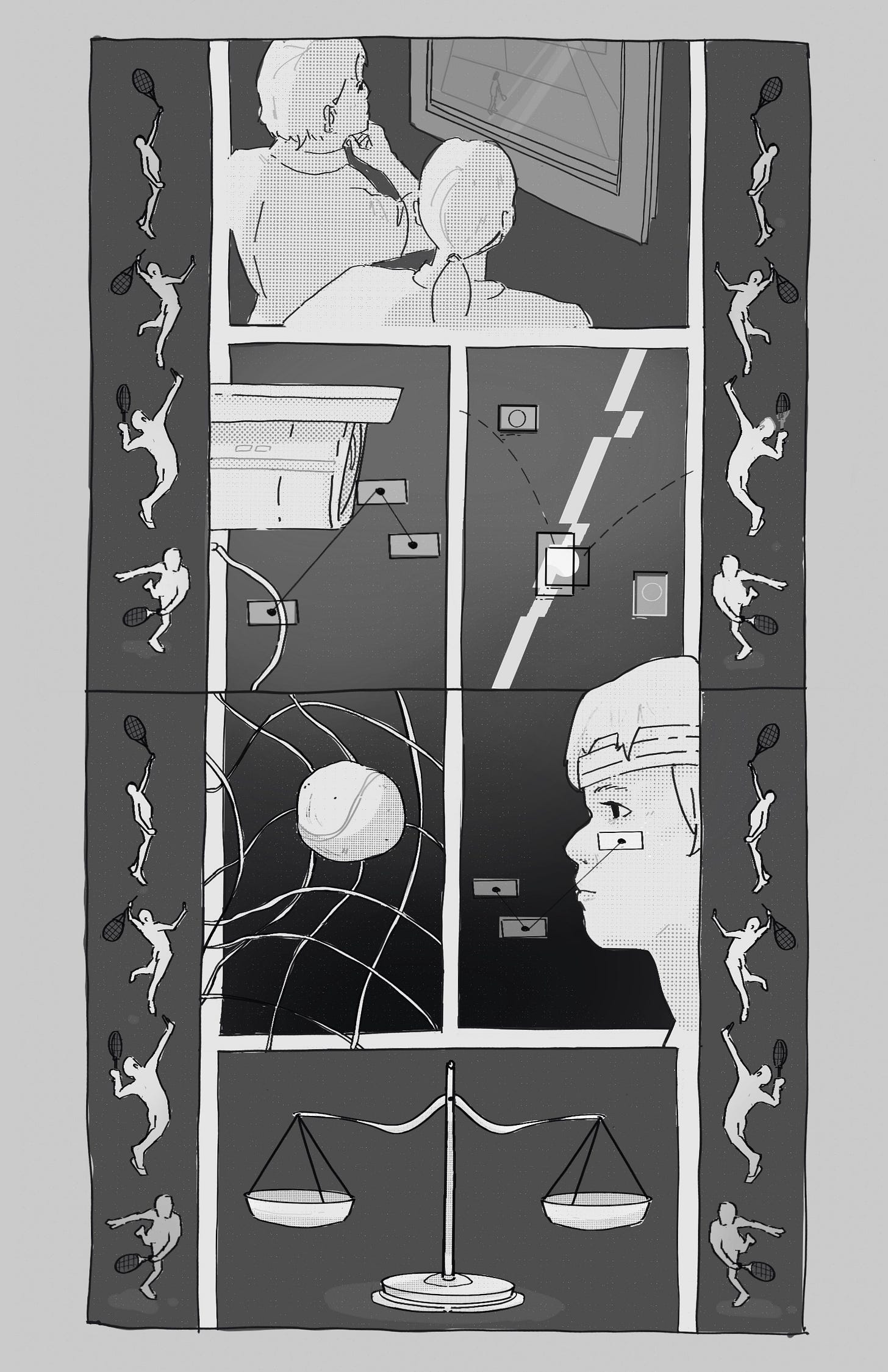

The lines on the court are the basis of the game, contours from which a sport is born. But the line does not contain the line call; rules on their own are abstract directives, entities of the mind. Through their enforcement, rules make reality. When a junior tennis player calls a ball out, for just a second she is master of life—that’s why we (sometimes) cheat. In Arthur Ashe Stadium or Margaret Court Arena, iconic venues of the sport, only through the human line judge could a point end and the match continue. So how does the game change when we hand over this reality-producing power to a computer?

The ATP, the highest level tour for men’s tennis, previously announced that by 2025 the entire tour will use electronic line calling (ELC). Most commonly, the Hawk-Eye system is used. Hawk-Eye works by creating a trajectory of the ball using computer vision input from up to 10 cameras positioned around the court. Because each point can only end with a ball in the net or outside the line, Hawk-Eye determines the outcomes of matches very concretely; unlike in other sports, automated officiating in tennis is not just used for penalties, infrequent goals, or out-of-bounds calls.

The press release announcing this move was brief, but it cited “accuracy and consistency as the most important factors in assessing different line calling systems.” Accuracy and consistency.1

We rely on computers to run increasingly large portions of our lives. That makes it easy to take for granted their dependability—their accuracy and consistency, perhaps?—whether applied to taxes or tennis. But the move to ELC obscures an important fact: on the closest of calls, it is nearly impossible to determine whether a ball is in or out with complete objectivity. It is and always has been a best effort. Where humans once stood (literally!), this was an obvious fact—we get tired, we blink at the wrong moment, or hair blows into our eyes, to speak only of benign faults. This is what brought computers into tennis in the first place, spurred on by a disastrous sequence of unsound rulings against Serena Williams in the 2004 US Open quarterfinals, which showed exactly how imperfect line judges could be.

Established in 2006, the challenge system allowed players a number of “challenges” to line judge calls, possibly overturning them. It used the then-new Hawk-eye system as a neutral party and final review of the call. Here was a system for error handling baked into matchplay, an acknowledgement that humans make mistakes and a mechanism through which they could be corrected. Seen only through the challenge system in those early years, the Hawk-eye demonstrated its clear impartiality. Seen only on close calls, it demonstrated its superior consistency—its accuracy.

Perhaps the most significant change with the new ELC rules is, then, the removal of a challenge system. Now that Hawk-Eye is primary decision maker rather than double-checker, there’s no fallback from its decision. Implicitly, the thinking goes: if the computer is more accurate and consistent than humans, why challenge its calls? Or, more explicitly: machines don’t mess up.

But you and I both know that can’t be true. We know that because while Hawk-Eye boasts an error margin of 3.6mm, even a rudimentary understanding of statistics tells us any error margin means Hawk-eye will call out balls in and vice versa. We know because we’ve seen our own computers glitch, freeze, and crash, often in unexpected ways. Hawk-Eye may be more accurate and more consistent than a human, but it is not infallible, as much as we may want it to be.

One of the possible new failure modes was revealed in last year’s Cincinnati Open, the summer tournament leading up to the US Open and one of the first tournaments to adopt ELC. In a round 1 match of Taylor Fritz v. Nakashima (and also in the first round of the Canadian Open in Tiafoe v. Tabilo), an out call by Hawk-Eye did not make it to court, which led players to continue playing as if the ball was in. (The rule of tennis dictating that an out-ball ends the point depends also on the ball being called out). In both instances, the umpire stopped the point abruptly, several shots after the wrong call, and replayed the point per rules at the time, citing “technical issues.” Understandably, players were upset – the ball was out, and they should’ve been awarded the point at that moment, rather than having to fight for it again. To accommodate, the ATP responded by changing this rule mid-tournament – allowing for points to be awarded retroactively if there was a delayed call.

ELC impacts routine play as well. Not yet fast enough to make calls at the speed of a human, electronic line calls often come a split-second later, during which players are left wondering whether they were right. It takes time to compute. But players reflexively stop when they think the ball is out, a behavior trained on decades of calls made by fellow humans with a similar reaction speed. On-court disputes look different too; Jelena Ostapenko, notorious for her rejection of ELC, was caught on tape at the 2025 Qatar Open apparently whispering to an on-court camera, possibly trying to get in its good graces.2

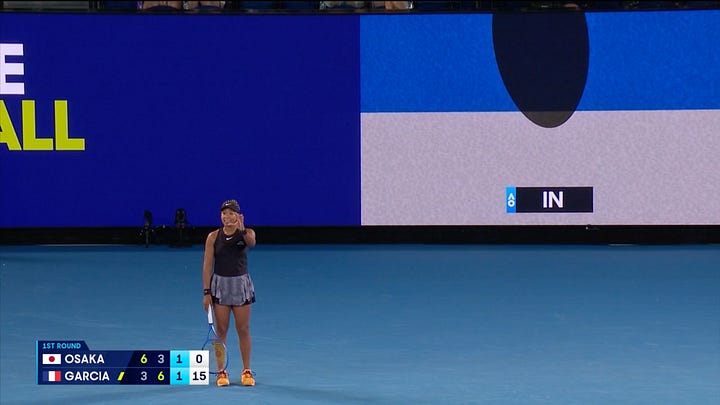

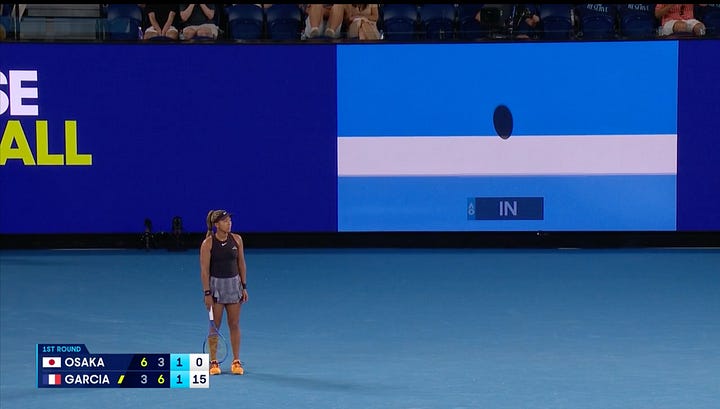

Watching the Australian Open this year, there were moments of incongruity with the machine. In the most memorable, on a ball called in against Naomi Osaka that she (and commentators) saw as out, the chair umpire told her, “You saw it differently.” Not a preposterous statement on its own, considering Osaka was moving to hit a ball coming faster than the speed of a car on a highway. But watching this clip back made the umpire’s statement feel like a harbinger of sorts, a glimpse into a world to come. When judged by computers, what else do we “see differently,” unable to make the computer “see” what we saw? And having no sight, what does a computer “see” at all?

Software, by definition, has no stake in our world. It operates on a rendering of it, on ones and zeros, measurements and approximations. Any attempt to imbue code with a sense of attachment would be as much a simulation. To the machine, it doesn’t matter if a call is in or out, regardless of how correct or incorrect its calculation might be—it’s just that, a calculation. To relinquish our involvement by delegating away this task to a machine is then to place a simulation above our lived experience. It is to subscribe to the computer’s synthetic reality, in all its opaqueness and dispassion, above our own. The frustration of a bad line call seemingly has nowhere to go—you can’t argue a calculation. “You saw it differently” rings hollow as an ironic consolation to the human. Your experience may have been real, but it is not the one that matters.

This remark also serves as a way to sidestep questions that arise with the use of ELC. For example: at what point exactly is a ball “in” on a grass court? If a blade of grass on which the chalk line is drawn brushes the tennis ball just barely as it flies over the line, though it lands past the line, is that in? Clearly, the human is not suitably evolved to make such miniscule observations about our environment, but is the computer? Could it be that we all (players, audience, commentators, umps) see the ball as out but the computer sees it as in? Whose experience matters then?

This was the subject of a recent ATP video promoting ELC on clay, aptly titled “Is Seeing Believing?” The French Open, the only grand slam on clay, has resisted adapting to the times in the name of tradition. On clay, challenges were reviewed not by Hawk-Eye but by the chair umpire, who would climb down from her seat to inspect the ball’s mark. Clay was the only surface where it was believed marks are clear enough to deduce whether a ball is in. Was believed. The whole point of the video is to show how marks in clay cannot be trusted—depending on conditions, marks that look in could be out, and vice versa. It was a primer for the future of clay. It also adds a twist to the claim that machines don’t mess up: saying that even if they do, we cannot dispute the calls, because we are not capable of disputing them. That even well-intentioned human involvement creates confusion and error, working against accuracy and consistency.

What must we give up in service of those two words? Trust in our senses, through which we interact with the external world? Each of our respective split-second masteries of life? Or should we simply learn to stop worrying and trust the computer? According to my brother, a fellow tennis player and fervent supporter of ELC (in late-night theoretical conversations; neither of us have experienced the technology first-hand), this new system is better because during a point, players no longer worry about a line judge calling the ball out. They can just focus on the tennis. This sounds familiar. Off the court, we are no strangers to the claim that technology will automate away all the little tedious aspects of life, performing better at them in order to free us towards some greater imagined potential. But what if these little measures are what comprise life itself?

I found the heart of this notion described beautifully in a recent edition of The Convivial Society: “To live is to be implicated.” L.M. Sacasas warns us not to

… delegate away a form of life that is full and whole, rewarding and meaningful. We ought to be especially careful in the cases where what we delegate to a device, app, agent, or system is an aspect of how we express care, cultivate skill, relate to one another, make moral judgments, or assume responsibility for our actions in the world—the very things, in other words, that make life meaningful.

And so I arrive, finally, at the point. To involve the human in affairs such as the line call is ultimately to make life more meaningful, and it may come at a cost. But the human as sole source and recipient of meaning cannot be replaced in that realm. When we speak of a court looking empty without line judges, is it not only the lack of physical presence we feel, but also of spirit, of mutual involvement with each other that gives rise to what we call life? I wonder if only by implicating ourselves in the enforcement of our rules do we create the possibility that they could be more than a calculation, more than an engineering problem, that they might also be matters of fairness, of education, of triumph.

The computer’s lack of self-implication is precisely that which gives the computer its impartiality. Assuming responsibility for ourselves and our actions remains a human-only capability, and it is the foundation of our collective exchange with each other. When we delegate “tasks” such as the line call to a machine, this responsibility dissipates. Made incapable of questioning its decisions and with no one to call upon even if we could, there is no choice but to obey the machine.

As it turns out, implicating humans in the line call does more than expose judgements to bodily defect and unconscious biases. Online, people have begun to notice unforeseen consequences of electronic line calling. Only a single pair of eyes is left on court—that of the chair umpire. Line judges were also called upon as witnesses to the goings-on of a tennis court, from disruptive fans to insect interferences, all the little things that happen in the sphere of the living world. By mistaking the judges as useful only insofar as accuracy and consistency of their line calls are concerned, we discounted their other contributions, many of them a result simply of a human being involved with human endeavours. The chair umpire now single-handedly accounts for all that happens on court, ironically lending even more burden on a single person and their limited senses to uphold fair play.

Furthermore, the removal of linespeople at the highest level of tennis could have a ripple effect on the sport as a whole. At lower levels, such as the Challenger tournaments, matches continue to rely on human judges, whose main reward given little pay is in contributing to a sport they love and a chance to one day maybe serve on the biggest stage. With this incentive removed, it is unclear whether line judges (who go on to become chair umpires) will continue serving the sport to the same extent as they previously did. Even within tennis, society turns out to be a complex web of relations and striving, one in which a machine may not fit as neatly as we would like it to.

In the end, no single call (human- or machine-made) can determine a match; that still remains up to the players on court. There’s always another ball you could’ve ran harder for, a point where your focus drifted, a game where you were simply out-played. And yet, I find myself coming back to the close call, to questions that are perhaps both out of style and out of play: How did we admit to ourselves that on certain calls, we would never know whether it was in or out? How did we play on anyways? And how did we play on knowing we had been wronged?

Hawk-Eye may well be the right call for the sport of tennis, and in the arena of automated rule enforcement, ELC is admittedly of lesser consequence. But as L.M. Sacasas notes, we would be remiss “to think that care, skill, judgment, and responsibility are only of consequence when the circumstances are grave, momentous, or otherwise obviously consequential.” It is worth remembering that we make up both the rules and the methods of their enforcement, and take responsibility for both.

It is worth asking ourselves very carefully: on exactly what basis do we choose to replace the human with the machine? They might be calling some of the shots, but we’d be wise to keep the final say.

Arushi Bandi is a technologist living and working out of San Francisco. She hates rules.

🌀 microdoses

World #1 Aryna Sabalenka on Wimbledon without human line judges -- players are just as conflicted!

... and more players commenting on what they think about Hawk-Eye!

Thank you all for reading about the flop sport of tennis.

Though, of course, these debates are quickly coming to the flop sport of baseball as well!

P.S: The long-awaited New York City Kernel launch event is happening on September 12 at Hex House! Stay tuned for more details.

Thanks for reading — if you enjoyed this essay, we’d really appreciate it if you shared or forwarded to a friend!

There are, of course, other factors we could consider when assessing different line calling systems. One might be safety—perhaps the reason Novak Djokovic, the men’s player with the most grand slams ever, has long been a proponent of ELC. In 2020, he accidentally hit one line judge in the head and another in the neck, the latter leading to a default from the US Open. For him, it seems the fewer people on court, the less physical danger he poses. Entertainment is another—John McEnroe (famously, “You cannot be serious!”) likes to think he would’ve been more of a winner but less of an icon with Hawk-Eye on court with him. And after all, the word “sport” originates from the Middle English word for “disport”, meaning “to enjoy oneself unrestrainedly, frolic.” The challenge system was notoriously a source of entertainment on the court. Do we enjoy ourselves more as players, audience, and judges now that the line call is one less worry?

We have yet to see all the changes inducted by ELC’s introduction into the sport, or rather Hawk-Eye’s. The director of tennis at the company previously joked that “out!” and “fault!” calls could be replaced by those of sponsors, such as “Ralph Lauren!”. This may have been a joke, but it echoes the very real possibility that the proprietary technology used in adjudicating line-calls could change with little, if any, oversight from players and other stakeholders.