My Biological Archive

Every day, we are saturated with an outpour of data and left to sift through the noise to find meaning.

As the resident biologist on Reboot EdBoard, I’ve always been fascinated by the ways tech has tried to quantify the data of life. That’s why I’m thrilled to bring you all this essay from Eileen Ahn on tech-driven collection of biological data, from 23&Me to workout tracking to (literally) swapping spit — what it manages to capture and what it can never quite catch.

— Jacob Kuppermann, Reboot Editorial Board

🧬 My Biological Archive

By Eileen Ahn

The month I moved to San Francisco, I was diagnosed with sciatica. Sharp and electric, the pain rose from my lower back down the nerve of my left leg, leaving me immobilized every few hours. Struck with an unfamiliar and unnerving pain, I was forced to learn and listen to my changing body as an adult for the first time. From sciatica to a six-month toe infection, an ankle sprain, and an allergic hive breakout, each new ailment taught me something new about my body: a single pinky toe injury was enough to tilt me off balance, and the ankle ligament was the essence of keeping me upright. At times, my relationship with my own body was shrouded by resentment and bewildered distance. My physical form seemed to be betraying me at every turn. Was this what it meant to have a body to take care of for the rest of my life? Would I ever learn or even come remotely close to knowing the workings of my body despite my occupancy?

I started weightlifting to alleviate my sciatica. I yearned to be stronger, to be rid of pain. More importantly, I wanted autonomy over my body again. As a novice, I had no prior knowledge of my strength or a gauge of the weights. A seasoned lifter friend recommended a workout tracker app, Hevy, to record my progress. On the app, I could enter data like the type of exercise, sets, reps, weights, and time. At the end of each session, it summarized my workout using digestible analogies such as, “You lifted a total of 16,640 lbs. That’s like lifting a T-rex!” It was silly, but this data felt sacred to me. Seeing my body grow and change through all the lifts and huffs, I learned that lifting means crafting form and repetition. Mastering fine movements generates a personal meaning inscrutable to any external observer except to be witnessed by one’s own body.

My left leg is better at balancing than my right, but my right hip is more flexible. Running is easier when I keep my torso straight. I am so much stronger than I think I am. Like a journal entry, my workout sessions, rendered in flesh and data, have become a biological archive that I have constructed, with personal meaning beyond its value to any external observer.

Today, anything and everything can be tracked as quantifiable data and biological data is no exception. Yet data collection and its usage are heavily obfuscated, even in its most seemingly anodyne forms. When I first heard of 23andMe’s ancestry tracker, I was intrigued by the possibility of knowing the biological mysteries of my body. Still, I didn’t feel too inclined to pay money to spit into a vial for a corporation to tell me, with all likelihood, that I am 99% Korean. Now I am glad I never did. 23andMe famously rose to stardom through a business model lush with cutting-edge biotechnology and an inflated promise to revolutionize healthcare. Their solution model paints the genome as a “data problem” that can be “cracked.”

Yet despite these lofty claims, 23andMe now walks a precarious line. At the core of its crisis is its recent data breach affecting millions of customers, with a $30 million class action settlement agreed upon last September. While hacks and data breaches have become common, 23andMe’s situation is perhaps more alarming: data breaches built on the purely digital or financial can be remedied through conventional means, but what about data breaches on the physical? While one’s genome isn’t enough to fully represent an individual, genetic data breaches and their potential misuses feel more dystopian than run-of-the-mill password leaks.

23andMe’s data breach reminds me of an old Korean folktale. The story begins with a man living in the mountains studying for a state exam. When he returns home, he finds a clone of himself. The family tests the pair to distinguish the right one, but the real son is ousted because he fails to recall detailed memories and family information due to his long absence. Wandering around with nowhere to go, he comes across a wise shaman (also retold as his ancestor or a mountain spirit) who tells him that a rat had eaten his carelessly discarded fragments of self, his fingernails, to take his appearance. He is able to catch the imposter by taking a cat home. The Joseon dynasty considered bodily materials with high value, treating everything of the body to be precious and sacred. Cutting hair was considered a cultural taboo, and in similar effect, Korean folktales upheld bodily parts, such as hair or nails, with power great enough to replace a person. The story serves as a lesson to keep even the smallest parts of the body precious, no matter how negligent or minuscule they may be. While I am not concerned that our fingernails are being capitalized to clone consumers, this old tale begs a question that is still relevant to this day: how are we disposing of, caring for, or archiving knowledge and material of the body? And who are the rats profiting off of such practice?

Many biotech companies like 23andMe focus their sales pitches solely on the explanatory power of the genome. Our participation in biological data collection has become normalized, infiltrating social and cultural spheres that would have once seen mention of haplogroups, biomarkers, or genetic screening as cold and clinical. However, by magnifying the most evident and observable piece of our biology, such a business mantra treats the body through a singular lens and flattens the rich complexity of its systems. No matter how much genetic data they may collect, corporations are still not able to quantify the phenomenology of our mind and lived experiences. They may never be.

In How Life Works: A User’s Guide to the New Biology, Philip Ball urges readers to “relinquish the idea that the ‘secret to life’ lies in the genome.” In his book, Ball comments on the flawed nature of analogizing the body as a cryptic algorithm or a machine. While circuits, algorithms, and mechanics may play parallel to the parts of the body, on a molecular level, cells can be random and unpredictable. To explain such a complex structure in the linearity of molecular components to output gene expression would be reductive. Ball writes:

“Living entities are generators of meaning. They mine their own environment (including their own bodies) for things that have meaning for them: moisture, nutrients, and warmth. It is not sentimental but simply following the same logic to say that, for we human organisms, another of those meaningful things is love”.

Put another way: our cells are constantly silently activating themselves and generating new, novel data for us — a personal archive of our own. It is this unique effort that makes each of our bodies all the more complex and our life experiences more meaningful in ways that cannot be captured by a mechanistic apparatus or the simple reading of the genome.

Every day, we are saturated with an outpour of data and we are left to sift through the noise to find meaning. When swimming in such vastness of data, the stories we tell and the intentions we set are some of the ways to make sense of the data. It is the intention to walk 10K along a windy path where I can see the neighborhood cat; the intention to finally add an extra 5 pounds on my dumbbell to know I will reach a PR I have been working on for months. These are the data stories only visible to the beholder. On the web, our digital footprints leave us relentlessly tracked and exposed, but in the physical world, some degree of solitude is possible. Our minds store intentions and passions known and felt by ourselves, and only ourselves. Our biological data is the same. In all the ways I do not know myself genetically or quantitatively, there are things I do know simply from having lived inside my body: My anxiety is held at the center of my stomach as a pitted seed or a rock. I clench my jaw when I am stressed or focused, which often causes migraines. My cold clammy hands and feet make me gravitate towards foods with “hot energy.” I have a disproportionately long torso and neck that have become a personality trait, invariably affecting my posture and gait. Such are the things that do not need genetic confirmation or a doctor's visit to tell me what I know from living inside my body.

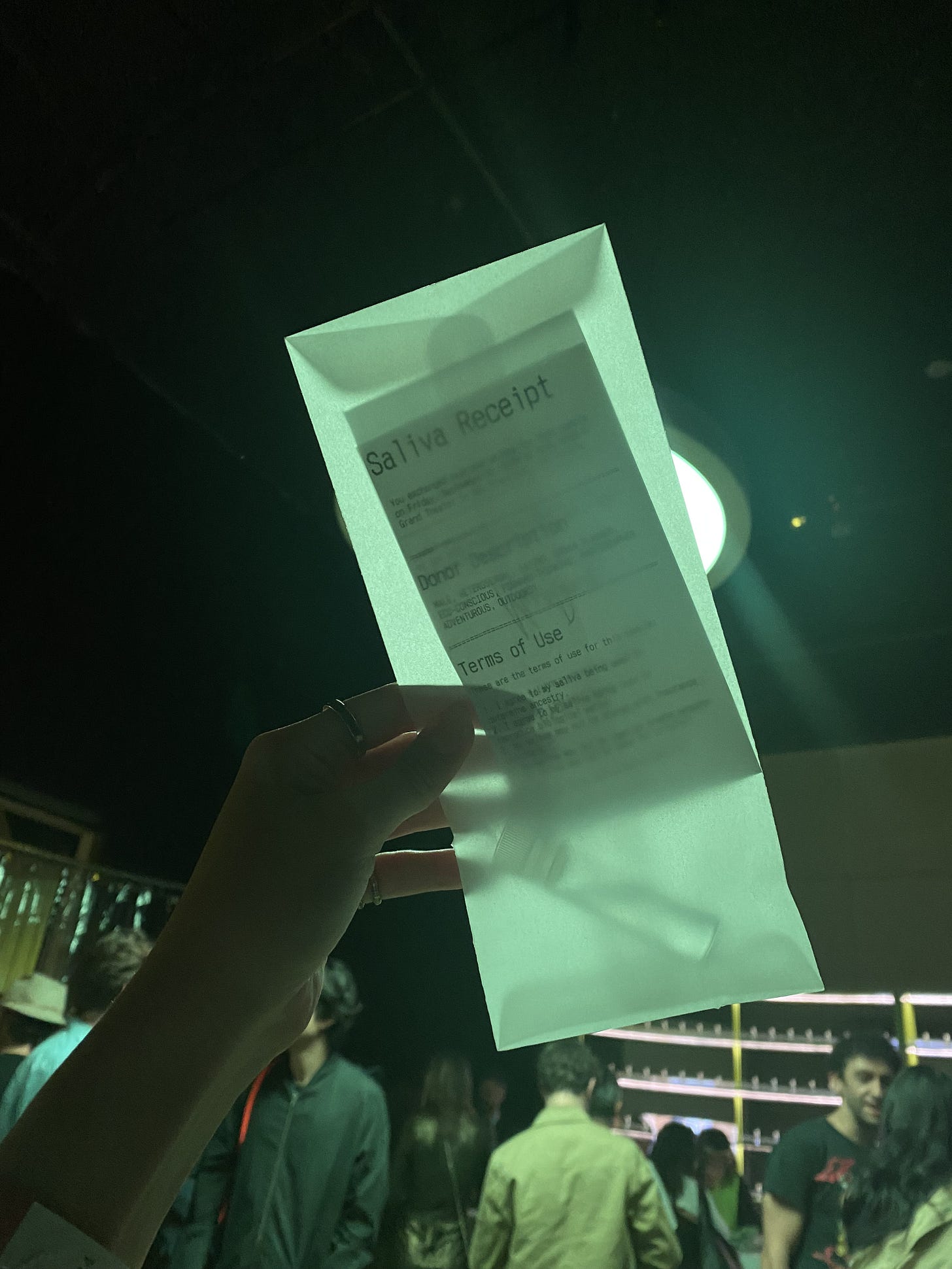

A few months ago, I had the chance to participate in Lauren Lee McCarthy’s exhibition Bodily Autonomy (Saliva Bar) at Gray Area. The exhibition invites visitors to voluntarily exchange saliva to “sidestep the anonymity of medical and corporate entities” and critique issues on data privacy and identity. Here, I spat in a vial, which I then labeled simply with demographic characteristics. In exchange, I received a vial of a person who labeled himself as a “male, heterosexual Latino who is adventurous, eco-conscious, forward-thinking, outdoorsy, urban planner, and photographer.” (If this is you, let’s connect! I still have your saliva!) This voluntary exchange of saliva also allows engagers to set their own terms of use: My saliva may not be used for weapons. My saliva may not be capitalized. My saliva may not be used for cloning.

McCarthy’s Saliva Bar is reminiscent of 23andMe’s very own spit party hosted at the 2008 New York Fashion Week. Unlike McCarthy’s Saliva Bar that gave autonomy to the spitter to remain anonymous, those gathered at the event did not have a choice for information anonymity in 23andMe’s data collection. But did the stakes really matter to the naive participants excited by the glamor of using their “genomes as a basis for social networking”? From Ivanka Trump to the Murdoch family, 23andMe CEO Anne Wojcicki had already garnered a wealthy group of socialites and investors during her launch. Wojcicki’s treatment of biological data is akin to Google’s understanding of the vast web and its data collection: a reductionist, data-forward, algorithmic scraping cloaked in glitzy technology to flatten users and everything in between. We are told to believe that their methods report unerring sources of truth. McCarthy’s Saliva Bar also serves as a critique of such a method that perpetuates simplified and capital-driven methods of understanding the body. Her exhibition examines not only the returned ownership of bodily substance, but also considers what it means to practice personal data collection not reliant on further capitalization of sequencing data. She asks, “Can I as an individual human become your saliva deposit center instead? Can we take saliva exchange back into our own hands?”

More days than not, I enter my data in Hevy – this practice feels ritualistic, but I am also reliant on its features to do the work for me. Hevy was made to collect biological data. The product would cease to exist without voluntary entries of its users. Their privacy policy does not mention selling or transferring user data to a third party. It lists an outline of user rights to data ownership including deletion, processing restriction, and rectification, although it may require a few hoops to jump through. However, privacy policy language tends to be abstruse, and once inputted digitally, there is no way of knowing its fate on the backend and all the parties involved.

Over the years, I have seen various lifters resort to analog forms of entry: pocket sized notebooks, a pad of sticky notes, and even a full composition book. In a similar light, I challenged myself to go through a workout session without Hevy. I listened to my body for guidance. I returned to my next set when my breath steadied instead of relying on a 2 minute ding. I sometimes took longer breaks or waited until the music ended. I stopped doing reps to follow the previously recorded number. I just continued until it felt good enough to stop. There was no counting, no automation, just bodily cues. This physical connection is perhaps the ultimate liberation.

I often find myself in a state of reluctant surrender to platforms. I convince myself, thinking but there’s no better way to visualize my progress or they give me trophy stickers when I hit a new PR or I can record post-workout selfies of my pump. But if there is another dilemma, it’s that the numbers and the data points I store present growth in a continuum of what is possible or could be possible as I push my physical boundaries with my body. The progress of these numbers shares a story, an effort to become more acquainted with my body.

But this story is inherently incomplete — and incompletable; the effort comes from knowing that some parts of my body will continue to remain a mystery. It will never be truly known to me, at least not fully. As I move through the world each decade, I know my body will continue to surprise me. As such, my body as it relates to the mind will never be fully known or quantified by medical practitioners, biological databases, or corporations. The best I can do is to listen and learn to understand, to reacquaint again and again to love as I am.

Reboot publishes free essays on tech, humanity, and power every week. If you want to keep up with the community, subscribe below ⚡️

EILEEN AHN is a SF-based designer and writer concerned with liberatory web practices and relation-mapping digital-physical porosity. Find her on Substack or online.

🌀 microdoses

CALL +1 844 992 2996 TO DIAL-AN-ANCESTOR

Heirloom Hardware is a fascinating design project looking at alternative modes of data storage for personal/familia/communal memory!

in conclusion:

💝 closing note

Thank you all for the pitches for Kernel Magazine Issue 5 — we can’t wait to share more about RULES with you! Creative piece submissions are still open until the end of the day today: inquire within for more details.

yay for personal archives!! thank u all for reading :~)

As someone who currently works in data protection in the medical/mental health field AND also did a degree in neuroscience where one of my thesis's was about epigenetics and biological reductionism, this was such a nice read that felt like it was meant for me (lol) - and touches on the need for humanity + the step away from looking at the digital tracking epidemic of our biology through a microscopic lens.