This piece started as a five-minute-long voice memo Allison sent me about a conversation with an Uber driver, the difficulty of finding an electric vehicle charger in Brooklyn, and the exploitative systems often underwriting lofty visions of technological solutions to climate change. In its final form, Allison has taken in the complexities and paradoxes of the renewable energy transition and written a sort of mission statement for workers in climate tech, one grounded in the material realities of our planet and the people on it.

— Jacob Kuppermann, Reboot Editorial Board

⛰️ Common Grounding: Bringing climate tech back down to earth

I'm in an Uber to LaGuardia Airport with my driver Jose. This is one of those occasional, magical long rides where we spend the whole time deep in conversation.

I tell him that I write software to coordinate charging for fleets of electric vehicles (EVs), e.g. recycling trucks, school buses, and commercial trucks. When I bring up how legislation in California will soon require all trucks entering the Port of Los Angeles to be electric, he asks if I’ve heard about the EV law for ridesharing apps in New York.

Starting in 2024, New York City required 5% of all rideshare trips to be dispatched to electric vehicles. In 2025, the benchmark will rise to 15%; in 2026, to 25%. Then, the requirements will increase by 20% every year, hitting 100% in 2030. To hit these goals, Uber is pushing drivers like Jose to lease electric vehicles, but he doesn't see the point since his gas car works fine. Moreover, Uber's $325+ weekly rental fees cut into drivers' meager weekly earnings of around $800, adding financial pressure while providing no path toward permanent ownership.

Even if he were to rent a Tesla, where could he charge it? Having a garage is rare in this city, and getting approval from your landlord to install a charger for your building is unlikely. So, drivers are left to scramble for a charge in the busy city streets, where chargers are currently few and far between.

I saw the lack of curbside charging myself a few days earlier at work, when we test-drove an EV in Brooklyn. We ran into every problem possible. Charging station apps were unreliable, with out-of-sync statuses and missing instructions. Whole Foods, our first stop, still appeared in the apps, even though its charger was removed months ago. Because it’s uncommon to be able to reserve a charger in advance, the next charger was occupied by the time we got there. The next station we went to advertised 18 available chargers; they were locked behind a gate, for private use only. Ultimately, it took us over an hour to find a place to charge.

Gesturing toward his phone in exasperation, my driver says that Uber is blocking him from receiving rides in Manhattan with no advance notice—ostensibly to prioritize EVs. He's forced to leave for Brooklyn, where fewer rides are available, resulting in a pay cut. Rideshare drivers across the city are experiencing similar app lockouts, a concerted effort by companies to keep drivers from meeting the threshold to receive minimum pay rate. In response, some are organizing with the Independent Drivers Guild to fight them.

As ridesharing apps push more drivers to switch to EVs, the situation above will become even more untenable. Together, Uber and Lyft comprise approximately 78,000 vehicles in New York City. Extrapolating from a 2022 study on electrifying the city’s ride-hailing fleets, the city would need 5,000 fast-charging ports to serve all these vehicles. Moreover, to make the EV transition realistic for rideshare drivers, future chargers would need to be installed outside of Manhattan, which has almost 60% of the city’s chargers. Queens, on the other hand, is home to 40% of the city’s ride-share drivers but has only 16% of the city’s public chargers.

Drivers are left to pay for the high costs of the EV transition with their time and money, while the city and companies get congratulatory news headlines. This is in line with the gig economy's track record of going to great lengths to avoid compensating its workers fairly. For example, gig work companies spent upwards of $205 million to pass Prop 22 in 2020, which classified drivers as independent contractors, not employees. Although Prop 22 is supposed to provide higher wages and health care stipends, California rideshare drivers are struggling to get paid for claims.

Even after our ride ended, I kept returning to Jose’s story. It brought me back to 2019, when I decided to leave big tech after leading an ultimately disappointing effort to improve the safety of riders and drivers on Uber and Lyft. Since then, I have spent a lot of time thinking about how to do ethical work in the tech industry. In 2022, I took extended time away from work to learn about climate change solutions.

I debated leaving software engineering behind, doubting whether I could make any positive impact. Seeing the record investment in climate tech startups convinced me to give the industry one more chance. Putting personal values and mission first in my job search led me to a job at a startup where I felt empowered to drive my own initiatives at work and grew the most that I ever had as an engineer. It was motivating to come to work every day, knowing that we were accelerating the EV transition.

Despite the tangible benefits of our product, I was growing increasingly anxious about the impact of green capitalist solutions as a whole on the physical world. I couldn’t shake the news headline that despite record renewable energy growth year after year, our global energy demand continued to grow at record rates. At the same time, I saw big oil acquiring EV charging software companies like ours while continuing to blaze ahead with fossil fuel production. Big tech, the supposed leader in net-zero commitments, was pushing forward with energy-guzzling AI initiatives while silently rolling back their climate commitments. Amazon, which emits more carbon pollution than the 72 lowest emitting countries combined, touted its electric delivery van program, although 98% of deliveries were still being made with gasoline and diesel. Israel, in the first four months of its data-driven genocide against Palestinians, had generated emissions greater than the annual carbon footprint of 26 countries.

At the same time, I was questioning going into the EV trucking industry. The benefits of mass EV adoption in the United States were clear: accelerating the clean energy transition, modernizing our grid, and reducing air pollution in heavily trafficked areas, which disproportionately affects marginalized communities. Despite these benefits, I was hearing more murmurs of the massive mineral requirements for EV batteries leading to a human rights crisis in the Congo, whose Katanga region contains the world’s most abundant, rich supply of the mineral cobalt. Seeing how well-funded we were in comparison to other known climate solutions, I realized that the most funded verticals in climate tech tended to be mere green mirrors to existing profitable sectors: electric vehicles and plant-based meats swapping in for ICE cars and livestock agriculture. These green doppelgangers might allow for a simple transition for consumers — but perhaps bring with them some mirrored environmental harms as well.

Once I discovered these gaps in my knowledge, I spent time learning, but the Uber ride with Jose was the catalyst I needed to bring everything together. Our conversation made me certain that the current pace of green growth advocated for by climate tech wasn’t sustainable. The net-zero school of thought oversimplifies a highly complex and dynamic natural system into a series of equations to solve. Its believers take a totalizing, one-size-fits-all approach. They power-rank climate change solutions by their total addressable market size and the gigatons of carbon they will sequester, min-maxing (to borrow a term from tabletop gaming) carbon accounting to reach neutrality.

However, this framing is shortsighted. When building software, it's easy to forget that we still operate in a physical world. One can deploy changes and see the impact instantly, or A/B two versions of a feature to see how they perform, plugging in software inputs interchangeably. Applying this gamified way of thinking to tackling climate change doesn't work so smoothly. We can't simply hit the reduce emissions button and reach net zero emissions or endlessly shift around emissions sources like they're pieces on a game board.

In the real world, our decisions are linked and have direct, material impacts which wreak havoc on our ecosystems. To supply materials for the green transition, global extraction of raw materials is expected to increase by 60% by 2060. Natural resource extraction has already risen by almost 400% since 1970. This excessive mining is already responsible for 60% of global heating impacts, including land use change, 40% of air pollution impact, and more than 90% of global water stress and land-related biodiversity loss.

As a result, we are creating a growing global archipelago of "sacrifice zones," forcefully disrupting and displacing communities. We're opening up the world's second most extensive peatland complex to mining for EV battery manufacturing in Canada. Over the complaints of residents, private corporations in Illinois are abusing eminent domain to break ground on carbon dioxide pipeline and sequestration projects.

To support the EV transition we’ll need a lot of batteries. The Paris Agreement calls for, along with global rail transport electrification, at least 100 million total EVs in use and at least 20% of road transport vehicles globally to be electrically driven by 2030. While a smartphone requires 5 to 10 grams of cobalt, a typical electric car requires more than 1,000 times that amount, between 10–20 pounds. To accomplish these lofty emissions reduction goals, production for cobalt will need to grow by almost 500% by 2050 from 2018 levels. Without regulations, ravenous mining companies treat the Congo as a toxic dumping ground in their scramble for minerals.

These time-lapse satellite images from 2017–2022 show the impact of cobalt mining’s breakneck expansion on Kolwezi.

The 200,000 artisanal and small-scale cobalt miners in the Congo toil all day without protective equipment. They use their hands or basic tools to extract ore, earning $0.80-2 at the cost of numerous health consequences: infertility and birth defects, cancer and skin diseases. Siddharth Kara’s Cobalt Red illustrates how they work in haphazardly built tunnels that frequently collapse, killing or severely paralyzing them. Without support from the cobalt supply chain, injured workers must send their children to work in their place. As mining expands, companies force the locals to relocate far away with forced evictions, crop burning, and violence. Kara warns: "When the cobalt finally runs dry, the world will carry on and leave Kasulo behind, just like a lion that has finished gorging."

Both Congolese miners and NYC gig workers labor for companies that treat them as disposable resources to be extracted and exhausted. These corporations squeeze as much work as possible out of them while crafting an opaque, untraceable system that ensures they owe as little as possible back to these workers. In broader terms, these drivers and miners are both victims of a school of thought on climate change that views their lives as inconsequential compared to the energy revolution that their land and labor provide.

Capitalism is designed to distance the consumer from what it actually takes to get their shiny end products, dissuading them from doing anything about it. However, to paraphrase a Congolese nun from Cobalt Red who has been documenting the impact of the Congo’s cobalt rush on her community: how can we hope to build a sustainable future by sacrificing the very bearers of that future?

The more I learned about the dark side of green capitalism, the more anxiety I felt about the future of the planet and the impact of my work. In the past, climate science fiction books and the solar punk community had gotten me out of these ruts, helping me imagine a future that was both sustainable and equitable. This time, I found inspiration in a board game called Daybreak. Several other climate-themed board games operated under the same green capitalism worldview described above. For example, in Catan: New Energies, investment in renewable energy is the sole lever to fight global warming. A single player can win the whole game, "regardless of how polluting that player's energy supply is," as long as they're the first to reach 10 points.

But Daybreak stood out from the rest. No one wins unless everyone does. Players must cooperate, assuming the roles of the US, China, Europe, and the Majority World. The Majority World role encompasses two thirds of the world’s population, which only emits a third of global greenhouse gas emissions, whereas the US, Europe, and China are the three biggest historical emitters of carbon. Unlike other games, the actions in Daybreak aren't just tied to decarbonization and energy. Instead, it's equally vital to take actions that build resilient communities, restore ecosystems, improve infrastructure, and bolster international cooperation. The winning conditions for the game aren't merely net-zero emissions. It's only possible to win if no region hits the limit of communities in crisis and everyone reaches Drawdown, the moment when we collectively remove more carbon from the atmosphere than we produce.

The first few playthroughs with friends were an anxiety-ridden hot mess. We barely collaborated, hustling to roll out clean energy quickly. We ignored the bright red “Communities in Crisis” markers at the bottom right of our boards and the social, ecological, and infrastructure Resilience tokens on the left. As our temperature bands rose with each round, adverse effects multiplied. Our situation rapidly and unpredictably took a turn for the worse. Rolls of the dice triggered our environmental tipping points, and Crisis cards seemed endless. We lost in the first few rounds by maxing out our communities in crisis.

One of us quickly realized the importance of these resilience tokens in protecting our communities from repeated crises. Still, we lost until we all began to invest in our strength and adaptability. Cards that we had previously discarded as worthless took on new meaning. Building robust social movements allowed us to draw many new cards and thus take more actions. Restoration projects like peatland rewetting helped us bring back carbon sinks. We won nearly every game with this new approach, which put community first, while still working on some more traditional decarbonization projects.

Although I'd already learned about these alternative solutions, I only internalized their importance after exploring them on the gameboard, a microcosm of the real world. We could see the impact of our decisions over a five-year span within a round. By taking a birds-eye view and studying the cards and their relationships to one another, I broke away from my ingrained belief that I needed to find the single most impactful way to tackle the climate crisis. I had the newfound courage and confidence to advocate for these solutions in real life. It was easier to see what I could do to fight climate change in my professional and personal life through individual and collective action. I'd been stuck thinking in black and white, debating if we should stop the entire green transition because it was hurting so many people. But living in this world means operating under complexity. Instead of fleeing from the situation, I knew that I needed to stick around, to push the levers to help where I was best suited.

I looked toward the scores of climate scientists who have realized that simply releasing research individually isn’t enough. They are uniting, using acts of civil disobedience and community engagement to catalyze societal change. Their potential actions vary across two axes, pictured below: individual to collective action and personal life (as a citizen) to professional life (as a scientist).

What could a chart like this look like for me, or any worker in climate tech? I started small, initiating conversations about the Congo and the heavy presence of fossil fuel corporations in the EV charging software industry with my coworkers. To make connections in the broader industry, I went to conferences and pushed myself to write on our company blog about what I learned. I tried to meet people in many roles and types of companies, including nonprofits and people leading citywide climate efforts. Beyond the EV industry, I joined a new LinkedIn group for fellow alumni in climate tech. I imagined building something like Tech for Palestine, which rapidly grew into a coalition of 8,000+ tech workers after a single blog post went viral.

As climate tech workers, we can join in solidarity with the Uber drivers and cobalt drivers making the green energy transition possible, who are as vital to the EV transformation as electricity itself. We could call for our industry to accept its responsibility in this inhumane system and elevate the perspectives of rideshare drivers and miners. They all deserve steady, reliable wages for their work and protection against injury and death. The miners need environmental regulations to protect their communities as well as electricity generation, education initiatives, and investment in their future generations. Drivers need ample charging infrastructure and the opportunity to eventually own the EVs that they’re renting.

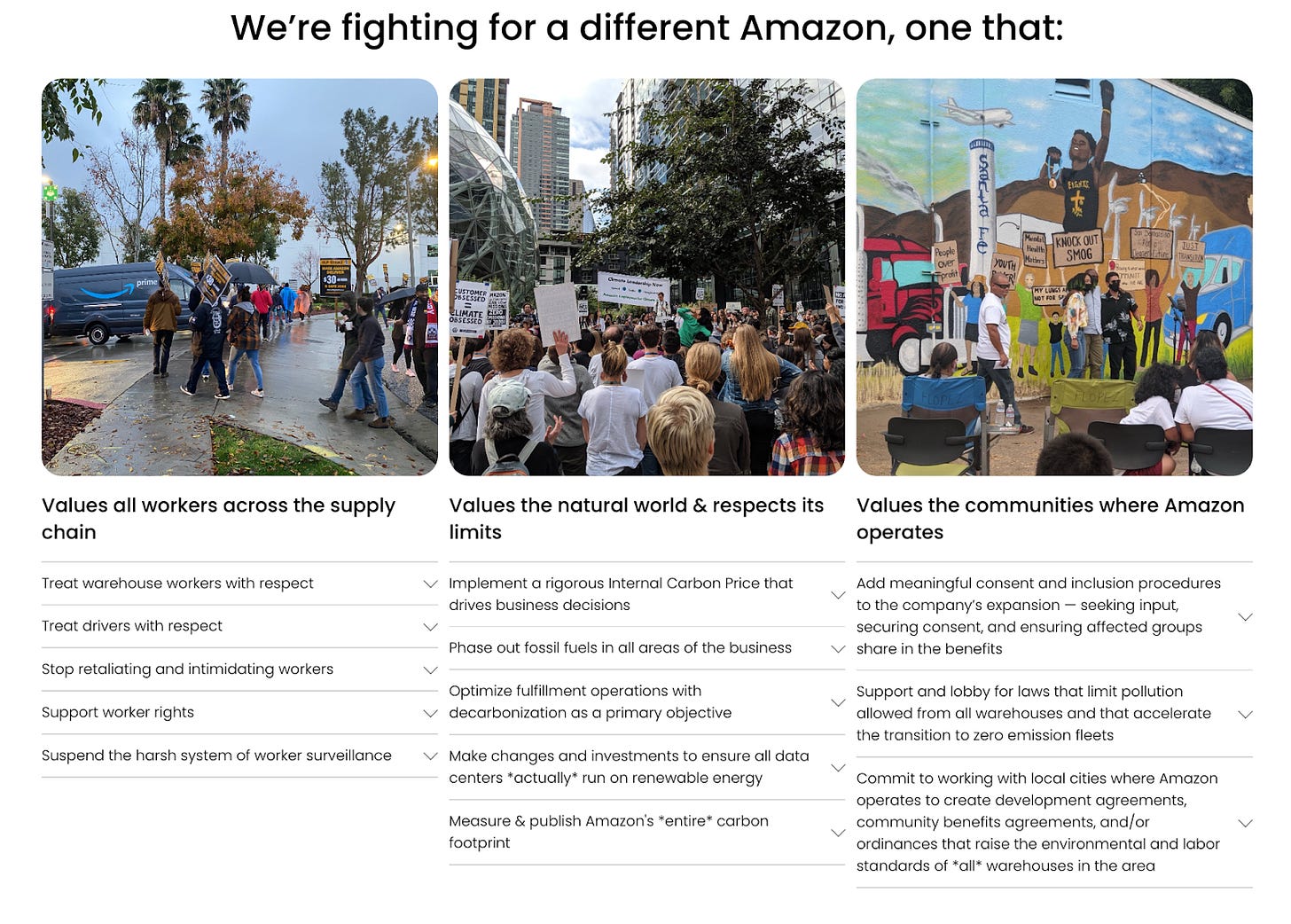

More broadly, we can lobby our local and state governments to take regulatory action to accelerate EV adoption, expand infrastructure that prioritizes walking, biking, and public transit, and build out public renewables. We can take a stand against the fossil fuel industry, pushing our employers to divest from fossil fuels in our 401(k)s, like the group Amazon Employees for Climate Justice, which has conducted research and staged walkouts to push the company to follow through on its climate commitments and take responsibility for its environmental harm.

On days that feel like my struggle against climate change is insurmountable, that the actions above are pointless, I return to grounding, re-attaching myself to the earth beneath my feet. This ground connects me with my environment, my community, and people from halfway across the world who share my pain. Grounding gives us a chance to come up for air amidst the deluge of corporate greenwashing and green growth idealism, to extricate ourselves from the digital realm and find our footing again. When we take time to ground ourselves in our material reality, we remember our unique strengths and spheres of influences and adapt the activism that we do to the current conditions that we are in. Unblocked, we can take small steps forward, toward a hopeful vision of a just transition. Together, we will refuse to let green capitalism own the narrative. Let’s demand more from our climate tech.

Reboot publishes free essays on tech, humanity, and power every week. If you want to keep up with the community, subscribe below ⚡️

Allison Tielking is a software engineer working on accelerating the EV transition. She’s driven a Class 8 truck (admittedly while screaming) and enjoys exploring community gardens and learning languages. You can find them on Substack at allison (@tielqueen).

🌀 microdoses

Some reading recs from Allison:

Adrianne Buller’s The Value of a Whale: On the Illusions of Green Capitalism

Ajay Singh Chaudhary’s The Exhausted of the Earth: Politics in a Burning World

Chilli is a very cool climate activism app/social hub!

Reboot editorial board member Morry Kolman has made the little red Thinkpad nub moan. Source code here.

Ok frankly I am obsessed with the Klamath river dam removal. They’re finding salmon in parts of Southern Oregon they haven’t been seen in for more than a century!!!!

💝 closing note

If this piece resonated with you, let us know! I’d especially be interested in hearing from other people working in the many different paths of climate tech — what are you doing in your own communities? We are also open for pitches and love hearing from our readers.

— Jacob & Reboot team

awesome piece!!!! so excited to read about climate tech on reboot