Today's guest edit is from my friend Humphrey Obuobi. Humphrey is a Product Manager at the nonprofit Recidiviz, which applies data to criminal justice issues. He also organizes with the Afrosocialist Caucus of DSA SF and hosts Zeitgeist, a new podcast on next-gen culture and tech trends. The first episode interrogates the difference between a job, hobby, and a side hustle.

I've learned a lot from Humphrey's writing on healthy social and information ecosystems: he's written this blog post on the topic for MisinfoCon and this reckoning on social media and movement-building. The essay he's sharing today is about the news app Tonic—it offers an inkling of optimism and a clear path forward in a field that desperately needs it.

📰 toxic to tonic: toward algorithmic agency

By Humphrey Obuobi

I have an app on my phone that I visit a couple days a week, only to close it when I remember that the product is no longer in operation.

On its surface, Tonic wasn’t too different from your average “daily content discovery” app. And yet, it was entirely different; by aiming to “build an alternative to endless feeds optimized for maximum engagement,” Tonic proved that “healthy engagement” can create a better experience than “more engagement”. Since it was acquired by CNN Go and went out of service, I can’t help but feel a gaping hole in my heart.

why am I so obsessed with Tonic?

The way Tonic worked was pretty familiar: every day, you got five (only five!) new articles, and the daily selection would evolve based on your engagement with them. As one might expect, a few simple behavioral signals were used to make this evaluation—things like which articles you tap on, or how much of each article you get through before abandoning it. Tonic’s pool of articles was sourced by an in-house editorial team that “scour[ed] the open web for articles, art and miscellaneous weird stuff.”

Other than this “quality over quantity” approach to content recommendation, Tonic’s key differentiator was that its proprietary algorithm never relied on personal information or social graphs to determine what content might appeal to you. In doing so, Tonic placed itself in a league of its own by showing that an app doesn’t have to feed off of our personal data—which we’re often unaware we’re giving away—in order to deliver a meaningful experience for users.

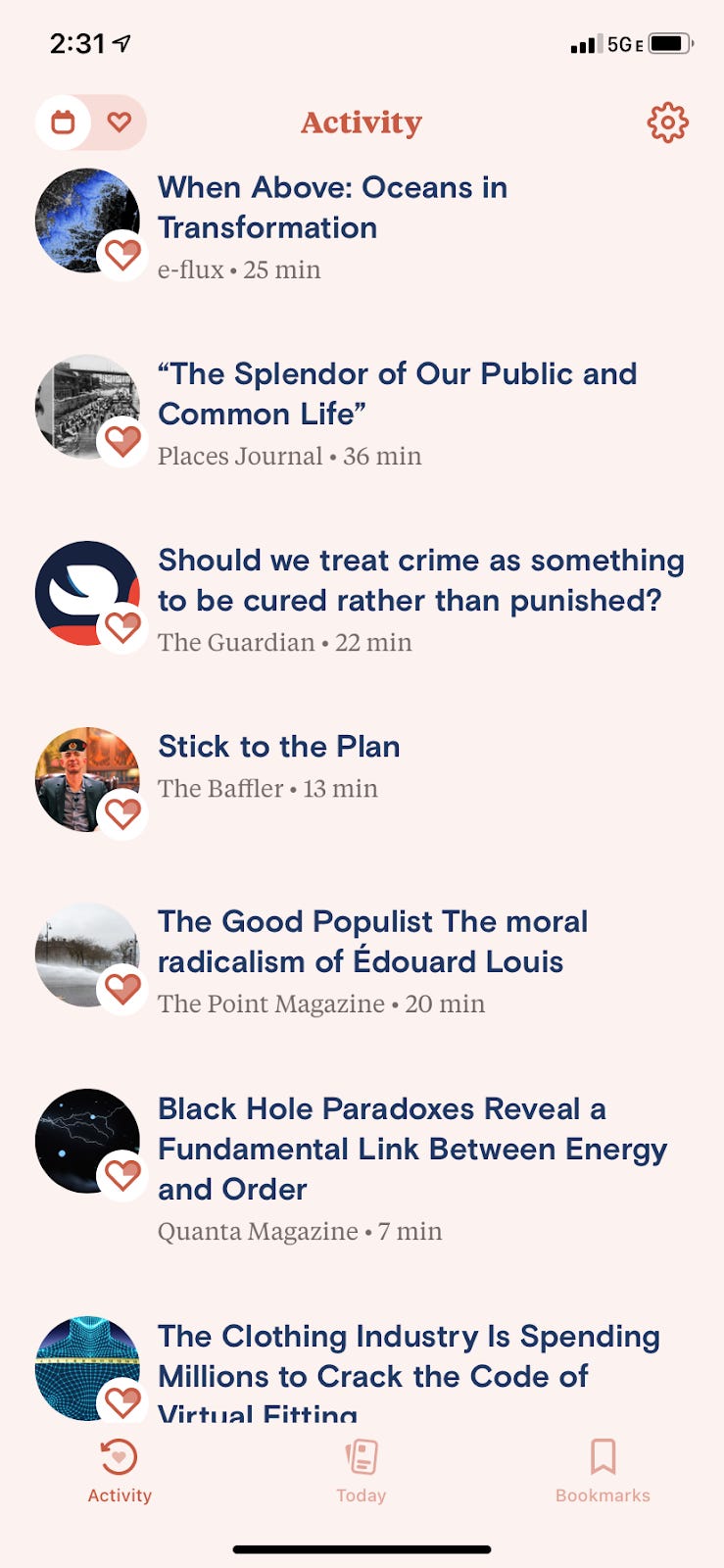

What interests me most about Tonic is that its creators understood that empowering their users didn’t stop with restricting the data that was collected; rather, the app directly involved users in how that data would be used to deliver content to them. The “Activity” panel in their app was special in that it actively encouraged users to review the algorithm’s assessments of how much you liked articles it delivered to you and even allowed you to tweak those assessments—or instruct the algorithm to ignore those articles entirely. Even better, this feature wasn’t buried deep in the settings (like Google’s Ad Personalization tools), but had a front-and-center position in the app’s interface.

algorithmic agency

This Activity Panel was an elegant solution to a need for algorithmic agency we’re starting to realize is important in our digital lives, a concept that is best illustrated by a few key principles:

Explainability. You should understand how an algorithm works: what the inputs are, and (generally) how the algorithm uses them to make decisions. With Tonic, we know that the information it uses is impersonal and based on your responses to the articles it feeds you. We don’t know much about how Tonic’s algorithm makes its predictions, but just knowing its constraints is helpful.

Transparency. You should have some visibility into the way a system is currently operating, especially the assumptions and judgements that the underlying algorithms are making. Tonic’s Activity Panel is a first-class example of this concept, revealing the history of articles along with the algorithm’s scoring of each one.

Control. You should be able to change various attributes of the algorithm’s operation. This mostly refers to giving people control of the assumptions and judgements that the algorithm is making; doing so can help us avoid seeing content that we’d prefer not to see, but can also help us improve our experiences. Tonic covers this base by allowing users to override any of the algorithm’s guesses in the Activity Panel—or ask it to completely ignore that article when making future decisions.

Tonic set out to create “[an] experience that evolves with you,” supplying insightful, funny, and inspiring content from the various corners of cyberspace. What’s special is that Tonic also set out to prove that this can go hand-in-hand with digital agency. In other words, more direct user participation can lead to a more personalized experience that still respects one's digital rights. Judging by the number of Tonic’s recommendations that are still part of my personal library, I’d definitely say they succeeded.

what's next?

Tonic was an excellent content recommendation engine, but it was very much built to optimize for personal growth and fulfillment. No social context ever entered into the decision to surface any particular set of articles, and the service never bothered to support any kind of social interaction—no comments, no “friends,” nothing of the sort.

But all media inherently exists within a social context, and how that information is produced and consumed has a huge influence on our behavior. Unfortunately, in the dominant social media platforms (e.g. Facebook and Twitter), we find algorithms and interactions that are far too ill-prepared to handle the ways in which people operate in socially—in communication, values, or otherwise. All too often, these products opt for static, aperspective interfaces in the name of scalability; the communities that inhabit the platforms cannot influence or control their design. The result is something you might have observed in the recent documentary hit, “The Social Dilemma”—platforms that radicalize, misinform, and generally contribute to the erosion of our social pillars.

It’s worth asking what alternative, healthier futures for social media could exist, and I believe Tonic’s principles were on the right track. If giving me a direct say in what content I value led to a better content experience, what could doing this within the context of an entire neighborhood (or city, or country) do? How can we grant communities the power to institute rules of engagement that operationalize their values and surface content more aligned with real-world concerns? What kind of social media elevates the voices of marginalized people rather than random influencers? What design patterns would lead to more collaboration and fewer petty fights (or outright harassment) online?

I’m still holding out for a platform that puts power back into the hands of the people and allows them to consciously and collectively control how content is delivered through collaborative algorithms and interfaces. There are some exciting projects that have started to explore the potential for “platform governance” in this way, and I’m sure the future holds many exciting possibilities.

In the meantime, I’ll keep opening the Tonic app every few days in the hopes that something new shows up.

what does your news diet look like today?

Humphrey: I probably rely a bit too much on Twitter to let me know what news I should be paying attention to! Other than that, I’m in a few groupchats (including my family WhatsApp group) that occasionally surface newsworthy happenings, and every now and then I’ll subconsciously open a new tab to www.nytimes.com.

how do you think about algorithmic ethics in your work at recidiviz?

Humphrey: My current work doesn’t deal too much with algorithmic ethics, but our world is chock-full of data ethics conundrums. Everything from the way we calculate certain metrics (like recidivism or revocation rates) or visualize specific data influences the way that government actors understand the problems within their system and act upon it—which can then influence the lives of any justice-involved individual. Our values are baked into all the data we deal with.

can you tell me about a book you loved this year?

Humphrey: My favorite book from this year is a random, relatively unknown book I picked up outside Adobe Books in San Francisco—Eastern Thoughts, Western Thoughts by Swami Kriyananda. It’s more or less a series of reflections on Western civilization, written from the perspective of someone who was raised in the West but then became a monk within a practice of Hindu philosophy. Lots of interesting insights on relationships between the self, community, and institutions.

Find more of Humphrey on his new podcast, on Twitter, or on Medium.

🌀 microdoses

🏙 How tech segregates us into real-life walled gardens

🔍 The Markup's "Simple Search" browser extension displays just search results, no filler

💹 Necroeconomics: interrogating the "Value of a Statistical Life"

🏫 Logic Mag is running a learning cohort for tech workers in Spring 2021

💇♂️ Guess the bad haircut

🌿 Plants can vibe too

💝 a closing note

Here’s the Reboot team’s news/reading stacks:

Jasmine: I subscribe to lots of newsletters, use Pocket to log past and future reading, and Readwise to save/manage web and Kindle highlights. I also love Goodreads and harbor a disgraceful preference for Kindle over print.

Ben: I have an RSS feed that has slowly evolved over the past 15-20 years and has way too many blogs/news sites now. They can pry this from my cold, dead hands.

Deb: Embarrassing, but I get most reading from Twitter and Substack. One thing I started doing that I like is keeping a little spreadsheet (I use Airtable) of the meta-data of the article along with a star ranking and any notes.

Em: I mostly use start.me (old school design, but highly customizable bookmarking tool and RSS feed) and the reader on Are.na. I find things through a chaotic mix of things my friends send, a handful of email newsletters, Twitter feed, Medium occasionally, and @novh on Instagram for breaking and NYC news.

We’re publishing two guest essays in a row in lieu of another November event, but we’ll be back with a new book talk next week! (It’ll be 5-6:30pm on December 1—mark your calendars).

P.S. We recently recorded a cute intro video. Check it out!