Silicon Valley is often selective about the activists it chooses to embrace. Aaron Swartz, the hacktivist persecuted by the United States for releasing thousands of paywalled JSTOR articles, is one who often makes the cut. But do the “boy genius” narratives around his Swartz’s legacy do a disservice to his cause?

👨💻 the boy’s own internet

By John D. Zhang

content warning: death/suicide

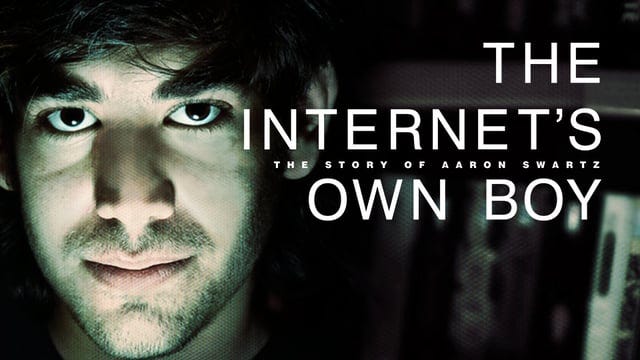

A few weekends ago, I watched The Internet’s Own Boy, a documentary about the life (and tragic death) of Aaron Swartz, the programming whiz kid turned internet activist extraordinaire who was prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law for the (arguably) victimless crime of downloading a bunch of JSTOR articles. In the documentary, Swartz is portrayed as nobly idealistic, spurning a lucrative career in the tech industry to instead dedicate his life to fighting the ills of corrupt government, an opaque legal system, and paywalled academic knowledge. Such a heroic, radical figure, the documentary implies, represented a grave threat to the powers that be. Before the opening credits conclude, the viewer hears disembodied voices making passionate claims like “he was killed by the government,” “they wanted to make an example out of him, okay?” and “governments have an insatiable desire to control.”

The allure and power of this narrative is undeniable. Swartz’s death led to outpourings of grief and protests across the world that reverberate to this day; indeed, the main reason I wanted to watch the documentary was the sheer number of my friends who have expressed admiration for Swartz or pointed to him as a key figure in their own political awakenings. I myself remember being in middle school when the campaign against the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) was in full force, watching my favorite websites like Reddit, Google, and Wikipedia stage a blackout to agitate their userbases. As a bored, extremely-online kid living in the suburbs, it was the first time I ever felt like I was part of a mass movement, though I don’t remember doing much more than signing a petition, upvoting some anti-SOPA posts, and maybe emailing a representative or two. I didn’t know it at the time, but Swartz was one of the key organizers of the campaign to fight SOPA, and as such he has left an indelible mark on my formative years.

Watching The Internet’s Own Boy more than a decade later, though, something feels off. Its anti-establishment, information-wants-to-be-free ideology, paired with its hagiographic treatment of Swartz, doesn’t resonate as much as it did back then. A careful examination — critique, even, — of Swartz’s approach (at least as portrayed in the documentary) might tell us something important about changing trends in how we collectively reason about technology’s role in social change, and allow us to honor Swartz’s boldness and idealism while critically questioning other aspects of his approach.

Swartz, one of the cofounders of Reddit, came into a windfall due to the Conde Nast acquisition and thereafter turned to political activism. Most of his activist work fell under the umbrella of the freedom-of-information cause, which is exactly what it sounds like: the idea that all people should be able to freely publish and consume information, often in relation to the principles of open access and free speech on the internet. Swartz’s multiple projects thereafter included Watchdog.net, a government accountability project, and the Open Library, an editable website with wiki pages for every book in the world. Swartz’s work on open access is mostly what The Internet’s Own Boy wants us to remember as his legacy, but it never digs deep into the question of why freedom-of-information, out of all the political causes Swartz could’ve worked on, was so dear to him. This question matters precisely because Swartz is seen as a role model by so many; the portrayal of what he cared about most has had real impacts on the life trajectories of many socially-minded technologists.

All sorts of injustices bothered Swartz, but the hoarding of academic knowledge by JSTOR must have seemed like it was begging for him to solve it. With his technical skills, he was easily capable of scraping papers from JSTOR via MIT’s campus network. We can’t know for certain what Swartz intended to do with the papers after downloading them. On one hand, his legal defense rested on the claim that he only wanted to perform “analysis” on the files, not distribute them. But you can read for yourself the views that Swartz espoused in “The Guerilla Open Access Manifesto,” a document he published in 2008:

Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves. The world's entire scientific and cultural heritage, published over centuries in books and journals, is increasingly being digitized and locked up by a handful of private corporations…Those with access to these resources — students, librarians, scientists — you have been given a privilege. You get to feed at this banquet of knowledge while the rest of the world is locked out. But you need not — indeed, morally, you cannot — keep this privilege for yourselves. You have a duty to share it with the world…There is no justice in following unjust laws…We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing networks. We need to fight for Guerilla Open Access.

Is information power? It must have seemed so to Swartz, whose skill in manipulating data via programming rapidly vaulted him into prodigy status at such a young age. But this kind of tunnel vision on the supposedly inherently liberatory nature of information dissemination is eerily similar to early failed visions of the internet, like John Perry Barlow’s Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace. Information might be powerful, but only in the hands of someone whose race, gender, nationality, and socioeconomic status allows them the authority to be taken seriously.

Examples of open-access initiatives failing to live up to their liberatory promises abound. Wikipedia, a website that Swartz adored, is free to all to access and to edit, and yet its community of editors is 85-90% male. Massively open online courses (MOOCs), which came into popularity at the same time Swartz’s activism was reaching its peak, promised to provide a new engine of social mobility; instead, it turned out that the vast majority of the people who ended up enrolling in MOOCs were employed young men with post-secondary degrees. These types of open access initiatives hold value, of course – rather, opening access is simply not enough to overcome the kinds of inequalities that information freedom activists so ardently claim to oppose.

The freedom-of-information movement had real, offline political consequences, too. As Dan Greene writes in The Promise of Access: Technology, Inequality, and the Political Economy of Hope, a wave of optimism about digital technologies created the hope that open access to digital services would fix the contradictions of the post-70’s United States, with its shrinking social safety net and vanishing middle class. STEM skills-training initiatives, like investing in 3D printer labs at libraries, became a political priority while funding for basic social services dried up, without any evidence that these programs actually resulted in increased material well-being for their participants.

This fetishization of information access imagines people in a vacuum, as if the only thing standing between them and a future of flourishing is whether data is open and accessible. However, access to a life immersed in knowledge-seeking isn’t just about whether information is free, it’s also about whether people are free from the constant demands of securing their basic material needs. Wendy Liu writes about the open-source movement’s loss of its radical roots in Logic, arguing that "truly decommodifying information will require decommodifying the things we need to survive in order to produce that information. To make markets less dominant in software, we must make them less dominant everywhere else.” It’s easy to imagine that Swartz, who was raised in an affluent suburb of Chicago to a father who was a software executive and a stay-at-home mother, might have taken these privileges for granted for much of his life.

Indeed, for all their differences, it’s hard not to notice the similarities between Swartz and the other supposedly great men of Silicon Valley. Musk, Zuckerberg, Gates: all white men from well-off families raised in wealthy or middle-class neighborhoods who started programming at a young age. This childhood prodigy status sets them apart from the rest of us; in the documentary, Swartz himself is said to have viewed programming as a “magical power” normal people don’t have. This messianic rhetoric is more than just off-putting or naive – it’s indicative of the kinds of people we think have the right expertise or authority whom we entrust with building our technological future. For contrast, the emotional intelligence, political creativity, and sheer resilience required to be a successful community organizer is exceedingly rare, but the media doesn’t seem to talk about it with the same reverence reserved for former boy geniuses.

The Internet’s Own Boy plays into many of these tropes, emphasizing Swartz’s technical brilliance and singular vision. But Swartz himself might have taken issue with that characterization: in a New Yorker article originally titled “The Darker Side of Aaron Swartz,” Larissa MacFarquhar describes Swartz as repulsed by the idea of merely asking for a glass of water from a waitress, because to do so would reveal the gap in status between himself and them. As he wrote on his blog:

Most people, it seems, stretch the truth to make themselves seem more impressive. I, it seems, stretch the truth to make myself look worse. At CodeCon the other day, all sorts of people asked me what I was working on these days. I could have said “I’ve been put in charge of Roosevelt Labs, a center to write cool software with political implications.” Or I could have said “I’m writing a book about how the world really works.” But instead I say, “Oh, nothing, just focusing on schoolwork.”

On his blog, Swartz wrote often about his neuroses and perceived inadequacies; it’s not a stretch to say that he was allergic to being seen as special or better than others. The appearance of inequalities, the visibility of asymmetry, seemed to have weighed heavily on Swartz whenever he encountered them. He even authored an anti-suit polemic in protest of how they entrenched inequality. I wonder if the internet had such an appeal to Swartz precisely because its inhabitants effectively appeared equal to another, without the encumberment of any visual markers of identity.

Swartz’s extreme sensitivity to difference, though, also seemed to impair his ability to form connections with others. Though he was curious about how people viewed the world, he found it extremely difficult to strike up conversations with strangers. He expressed sympathy for people experiencing homelessness, but also described feeling extreme “existential terror” walking around in San Francisco due to the “gangs of leering indigents.” In college, he wrote frankly about his own internalized tendencies to socialize primarily with other white people and ignore his Asian peers. On interacting with Deaf people, he wrote:

They’re just a little weird, with their pops and grunts and handwaving. When we invest so much on getting to know people based on conversation, what do we do with people who talk different? I didn’t have these problems on the Net, where the major differentiator was whether you talked in capital letters or not.

I can’t help but wonder if Swartz’s acute attachment to information systems created a tunnel vision that functioned both to the benefit and detriment of his activism. Reading books in libraries led directly to his political awakening, and his success in digital startups granted him financial freedom to pursue advocacy. At the same time, it seemed that the digital world was also his refuge and escape from the messiness of social life, where he could avert his gaze from certain problems of difference entirely. There’s something a bit frustrating about how the poster boy for lefty internet activism mostly treated information inequality as if it were independent from racial or gender inequality, preferring to work on his own or primarily with other technologists and lawyers rather than to participate in more diverse coalitions. Had he done so, the events of his indictment might have come as less of a surprise.

The response to Swartz’s actions — prosecution under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act by the state — was horrific and unjust. The threat of jail time, the draining of millions of dollars of his and his family’s money, and the enormous emotional toll of fighting an uphill legal battle culminated in Swartz taking his own life in 2013. And still, I couldn’t help but ask as I watched the documentary: why didn’t Swartz see this coming? As Bryan Stevenson, the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative and author of Just Mercy, points out in a brief appearance during The Internet’s Own Boy, what happened during the prosecution of Swartz is only surprising if you exist in a world where the prison-industrial complex does not routinely ruin lives or break up families on the basis of legal technicalities. That reality might exist for the rarefied, privileged circles of Swartz’s milieu, but of course, most poor people and people of color inhabit a very different one. Stevenson’s portion of the documentary is the closest we get to a theory of carceral repression by the state beyond mantric platitudes like “the government was out to get him” and “information wants to be free.”

In summary, Swartz was likely performing a direct action extremely in line with his personal value system when he scraped those files from JSTOR’s servers. What isn’t clear is whether that personal value system was tied to a coherent theory of other people’s material needs, nor whether the action was informed by a basic understanding of the carceral system and the impact it would have not only on him, but his loved ones as well. And if one’s idea of justice is rooted in one’s intellectualization rather than in community, and if one then acts without a tactical understanding of one’s own power relative to the state’s, then is that act part of any real strategy? Or is it just a stunt?

The Internet’s Own Boy is part of a long lineage of Silicon Valley media that speaks glowingly of boy geniuses with singular intellects and quirky personalities as society’s liberators. But Swartz himself didn’t want to be seen as a prodigy, and he didn’t see himself that way. Beneath the self-effacing tendency towards insecurity, Swartz was motivated by a deep sense of the fundamental equality between himself and others. The terms “prodigy,” “martyr,” and “hero” do work to place Swartz on a pedestal he expressly did not want under his feet. In fact, he saw himself as a good engineer but a mediocre political activist. Furthermore, the aspects of his personality that did set him apart from others – the difficulty he had working and cooperating with others, his many faults and biases, some of which he acknowledged publicly – may also have presented setbacks to his ability to engage in more community-based change.

I see these traits as a metaphor for how Silicon Valley often thinks about change – as led by great individuals whose expertise grants them authority to re-engineer society from the top down. This reliance on individuals, when applied to societies, impairs rather than develops our capacity for building real social change. It invisibilizes the way that technology is part of a larger set of social systems, hampers our collective self-efficacy, and elevates cults of personality over coalitions rooted in community.

Near the end of his life, Swartz became more involved in collective projects beyond the technical projects that he built on his own. He helped launch the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, an initiative to elect more progressive candidates, and co-founded Demand Progress, an online-intensive grassroots organizing group. The fight to stop SOPA was itself a historic collective mobilization. But The Internet’s Own Boy doesn’t investigate the changes in how Swartz thought about these types of work, nor which of his projects were more effective than others. The Internet’s Own Boy is simply interested in Swartz himself, uncritically flattening the various projects he worked on as if they were all just slightly different manifestations of his unchanging and unquestionably good theory of change.

The Internet’s Own Boy attempts to conclude on a note of hope by pointing us to another prodigy, a fourteen-year-old boy from Baltimore who, because of his access to JSTOR, was supposedly able to develop an award-winning test for early detection of pancreatic cancer. (Ironically, this research has since been called into question by eminent scientists, and over the years the researcher himself has distanced himself from his sensational claims.) Like the rest of the documentary, this conclusion feels a bit hollow, uninspired in its naive optimism centered around a single person.

By exploring different endings, we prompt ourselves to think about different ways of thinking about change in Silicon Valley. More generative questions, explored through the successes and failures of Swartz’s life, could have been: What are the limits of online organizing? Can information ever be free if the people producing it aren’t? What more could Swartz have accomplished had he been working in concert with a more diverse coalition of activists?

If there was one thing Swartz was, it was relentlessly critical, both of himself and the world around him. And as a sociology enthusiast, he cared deeply about taking the systemic view, interrogating the larger forces that structure the world around us and our positionality within them. The lesson I take from Swartz’s life — the tragic failure of his lone effort with JSTOR and the success of the internet community’s mobilization against SOPA — is that we don’t need more prodigies. To borrow a phrase from Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò’s Reconsidering Reparations, we need projects in collective world-making. ✸

John D. Zhang (he/him) is a software engineer and essayist based in the United States. He’s most interested in how technology mediates our affective realities – how it structures what we want, desire, and hope will come true.

Reboot publishes essays on tech, humanity, and power every week. If you liked this or want to keep up with the community, subscribe below ⚡️

🌀 microdoses

On the fraught relationship between the DWeb (decentralized web) and the web3 boom—and the power of financialization to energize and/or destroy a decades-old movement to decentralize the internet.

“It was always 2 am on the internet; it was always a sleepover after somebody’s parents had gone to bed.” Read Helena Fitzgerald on growing old online.

Boys don’t get better at texting when they get a billion dollars.

💝 closing note

We’d love your take on this essay, Aaron Swartz, and/or the future of information activism. Reply to this email or contact jasmine@joinreboot.org if you’d like to submit a short reader response to be featured in the newsletter (past example here).

In the next months, we’re introducing you to the amazing folks who lead Reboot projects. Check out this new Q&A with fellowship lead and creative technologist Ivan Zhao:

Toward collective genius,

Jasmine & Reboot team

brilliant brilliant brilliant