Kernel Magazine Issue 5 is out! We’re sharing another piece from the issue — Eliza Steffen’s look into the strange coalitions and new political alignments in the evolving world of reproductive tech. If you were at the Kernel Launch in SF, you got a sneak preview of this piece! For the rest of you: get your copy of the magazine now!

—Jacob Sujin Kuppermann

📏 repro/acc?

Edited by Shohini Gupta and Jacob Sujin Kuppermann

Growing up in the reproductive rights and justice world in the Midwest, my circle of concern was limited to what was under threat: legalized abortion, access to hormonal birth control, and funding for maternal healthcare. It took me well over half a decade later to see technology as part of the picture, when I belatedly came across Shulamith Firestone’s revolutionary second-wave feminist manifesto, The Dialectic of Sex. In it, she argues that only the development of an artificial womb, or “ectogenesis,” could truly liberate women, freeing them from the disproportionate burden of reproduction. Though kernels of Firestone’s ideas have been adopted by xenofeminists and a few other scholars, they have not garnered broader support within feminist movements. Over half a century later, Aria Babu’s Works in Progress essay, Womb for improvement, argues for the artificial womb on the grounds of scientific progress, urging us to create a world with the “first human being born without pain.”

I was immediately convinced by their arguments and later surprised to learn many of my female friends were skeptical of making ectogenesis a reality. To my peers, artificial wombs felt like a dangerous distraction from more immediate societal inequities for women, like paid family leave. To me, artificial wombs felt like an transformative opportunity to reduce the suffering often inherent in pregnancy and birth. I viewed the possibility of misuse and likelihood of initial inequity and access as acceptable risks, and thought that policy changes like paid family leave and technological interventions were not in competition for public support and private funding.

According to the most optimistic biotech enthusiasts, we are at least a decade away from artificial wombs. In the meantime, I wanted firsthand experience with this newfound world, and egg donation felt like an obvious option. Huddled in a corner of a sprawling house in Berkeley last December, a Stanford PhD student detailed her egg donation experience to me: the months waiting for a potential match, when the agency scheduled retrieval in the middle of a friend’s wedding, and the discomfort of hormone injections. I was fascinated by the idea of passing on my genetic material well before I felt ready to create children I was responsible for, and receiving a chunk of cash in exchange. If I proceeded, I knew that my experience would exist against the background of an ever-evolving set of disputes on reproductive technology.

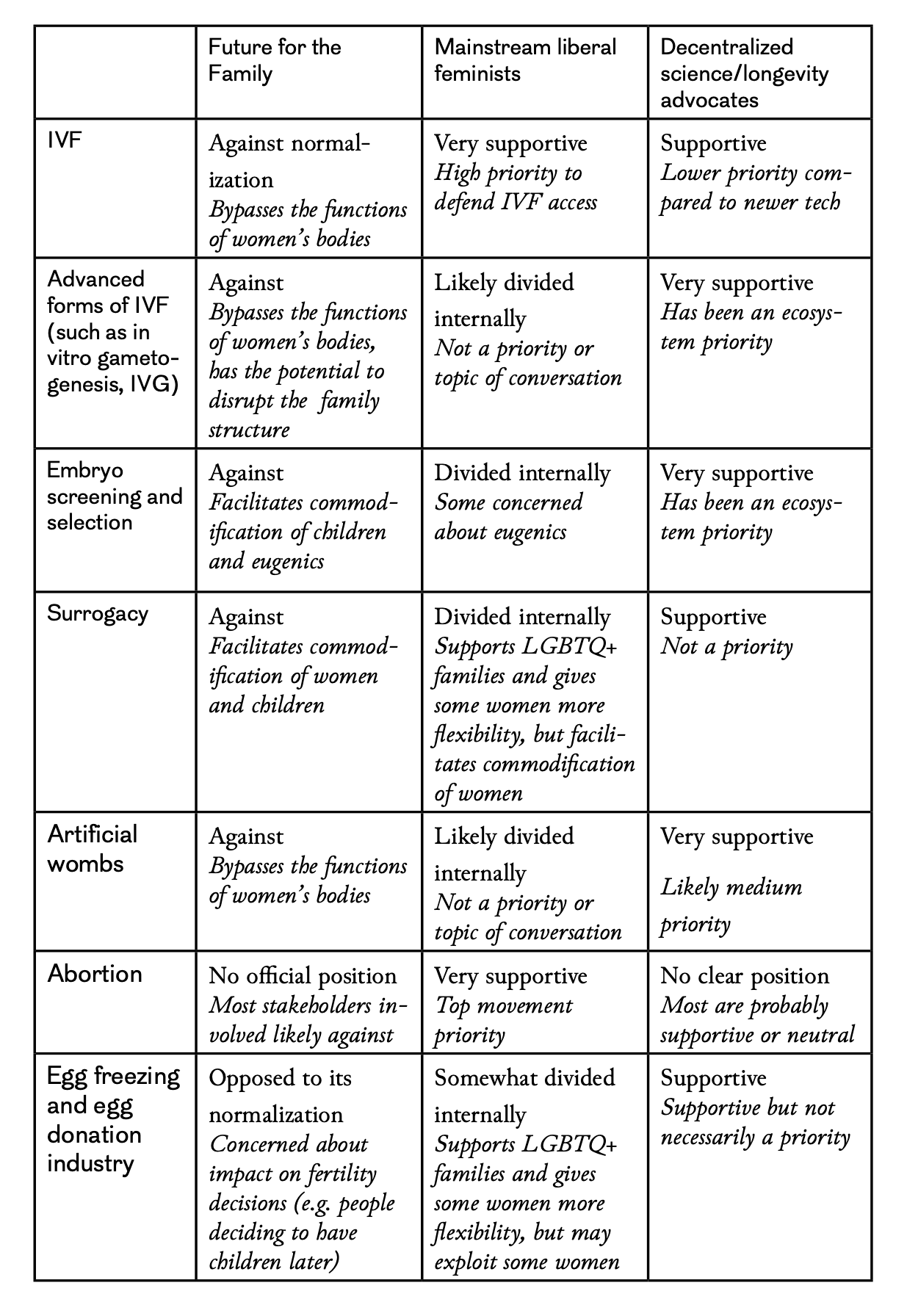

Recent years have seen several significant advances in reproductive and fertility technology. IVF use in the U.S. has increased by around 50 percent over the last decade, while companies like Orchid now allow parents to screen embryos for hundreds of conditions. More disruptive technologies are on the horizon: several companies are working on in-vitro gametogenesis (creating embryos from stem cells), and others are exploring the final frontier of artificial wombs. This has pushed some movements—including social conservatives and decentralized science and longevity advocates—to develop new or refreshed principles around reproductive technology.

However, these principles do not address reproductive technology in isolation; rather, they are often designed to advance broader ideological goals. For social and religious conservatives, this means the preservation of the nuclear family with traditional gender roles; for decentralized science and longevity advocates, advancing libertarian and transhumanist ideals. Meanwhile, most mainstream liberal feminist organizations have passively followed along with advances in reproductive technology, without a clear and proactive set of principles. Liberal feminists have been broadly reactive to shifts in the landscape, scrambling to defend older technologies like IVF and combat data privacy risks from period-tracking apps—while not prioritizing emerging technologies. Some of these movements connect their goals on reproductive technology with the growing pronatalist movement and concerns around falling fertility rate (though this is not a focus of this piece).

In early 2025, a group of mostly Washington-based think tanks, including social conservative mainstays like the Heritage Foundation and the Ethics and Public Policy Center, launched an initiative called “A Future for the Family.” The Foundation for American Innovation (FAI)—a right-leaning think tank focused on technology policy that has rapidly gained prominence over the last several years and generally does not take institutional positions—is one of the four core supporters of the project. At first glance, this set of ten principles to “govern tech in service of human dignity” is primarily opposed to newer and more disruptive reproductive technology like polygenic embryo screening and artificial wombs, as well as more controversial social technology like commercial surrogacy. However, its authors are also critical of more commonplace reproductive technology, including opposition to the normalization of IVF and criticism of hormonal birth control. In my reading, the principles they put forth are:

Anti-commodification: Any technology perceived to be commodifying women and children should be opposed.

Pro-naturalism: Restoring or healing reproductive function should always be prioritized over "bypassing" the functions of the human body, particularly women's bodies.

Anti-choice: Reproduction should not be subject to human will or choice—humans are begotten, not made.

Are these principles something new, or simply a retooling of a long line of conservative approaches to reproductive technology and medicine? Social conservatives have been thinking about the future of reproduction for decades. The idea that humans are begotten, not made and that fertility should not be a matter of human choice has been a core principle for social conservatives, appearing in the United States Catholic Conference’s official position on reproductive technology in 1998. And over twenty years ago, The New Atlantis, a publication of the Ethics and Public Policy Center, published the social conservative case against developing artificial wombs. However, Ari Schulman, one of the primary architects of Future for the Family and the current editor of The New Atlantis explained that the Future for the Family coalition is responding to what it views as the greatest emerging threat: Silicon Valley. To him, the technology industry is now far more dangerous than social liberals: “Fifteen years ago your enemy was the left. Now, it’s Silicon Valley, because that’s where the power is.”

To respond to the shifting power dynamics of the last decade, Future for the Family revises long-held social conservative principles in a key way. With the inclusion of anti-commodification, it allies itself with a diverse group of advocates—including those from disability justice and economic justice communities. Both Future for the Family and some economic justice groups oppose commercial surrogacy due to concerns around economic exploitation. In 2020, second-wave feminist leader Gloria Steinem and several progressive members of the New York state legislature opposed legislation to legalize paid surrogacy, with Steinem stating that “women in economic need become commercialized vessels for rent.” Like economic justice advocates, Future for the Family primarily opposes surrogacy because it creates an unacceptable opportunity for the “commodification of the female body”—though they also name their pro-naturalist stance as another source of opposition. Similarly, both Future for the Family and some disability justice advocates have opposed advanced polygenic embryo screening—and even more commonplace screening for Down Syndrome and Tay-Sachs disease—based on concerns around eugenics.

On the other end of the spectrum, an amorphous collection of longevity and decentralized science organizations (VitaDAO, DeSci NYC, Prospera) have emphasized experimentation and rapid technological advancement—with a growing interest in reproductive technology. These two ecosystems are deeply intertwined, sharing many of the same core organizations and leaders, a broadly libertarian political orientation, and transhumanist goals. Broadly, the principles that have governed this ecosystem are:

Anti-suffering: Technology should can and should be used to reduce and eventually end the significant amount of suffering (illness, old age, death) that the physical human condition entails.

Anti-naturalism: Technological advancement will not interfere with or change human “nature” in a way that we should be concerned about.

Pro-freedom: People should have as much freedom as possible to advance technology without limitation from the government or other forces.

Within reproductive technology, two categories have been prioritized by this ecosystem: embryo screening for a range of traits beyond life-threatening conditions, and, to a significantly lesser degree, reproductive longevity. These types of technology most clearly fit into existing ecosystem priorities: creating “better humans” and living longer. Reproductive technology has also come into play in the ecosystem’s growing forays into alternative forms of governance, such as charter cities like Prospera, and autonomous zones that would give reproductive technology advocates the legal freedom to accelerate technology. Though their emphasis has been on self-experimentation and clinical trial acceleration, they’ve also advocated for removing limitations like bioethics rules that prevent scientists from growing embryos in a lab past a few weeks, which currently prevent the clinical trials necessary to develop artificial wombs.

Out of hundreds of organizations in this rapidly growing space, there is only one decentralized science organization focused solely on reproductive and women’s health technology. Founded in 2022 by Laura Minquini, AthenaDAO is an autonomous community of reproductive technologists who often identify as “f/acc”, or fertility accelerationists. Since its founding, AthenaDAO has grown to around 27,000 members and deployed around $1M in funding. Ovarian longevity is one of AthenaDAO’s top research priorities, which its community sees as critical for both expanding women’s fertility options and key to answering broader questions on human longevity. Compared to the more explicitly transhumanist goals of its partner organizations, Minquini says that her broader goal is to help women and families and increase access to technology, saying “to me, the biggest end goal is that [reproductive technologies] are evenly distributed.” She is also more cautious about the implications of embryo screening and other reproductive technology prioritized by decentralized science and longevity leaders, noting that Margaret Sanger, the founder of the birth control movement, was a eugenicist whose work aimed to control the fertility of women of color. However, Minquini’s perspective is not often represented in decentralized science and longevity spaces: Minquini expressed that many leaders in the ecosystem are dismissive of ovarian longevity research, and AthenaDAO is rarely included in governance and policy initiatives, such as new charter city projects.

Meanwhile, mainstream liberal feminists have been focused on other issues within reproductive health: since the fall of Roe v. Wade in June 2022, abortion rights have taken priority. On occasions when technology has become a movement priority, it has generally been about defending IVF (and challenging conservative political leaders to do the same) or protecting data privacy rights for those seeking abortion care. There are several potential reasons behind this. First,movement organizations are exhausted and distracted by fighting for abortion access. Second,they do not view reproductive technology as an important issue to develop positions on. Finally, there is likely significant internal division over technologies like surrogacy and advanced forms of IVF. Schulman leaned towards the latter, noting that “My sense has been that there’s real internal division on the left, but real fear about advertising that.” One reproductive justice leader suggested to me on background that all three reasons are contributing factors. Given the focus on abortion rights, she surmised that only something truly concerning to the general public—like an announcement from a polygenic embryo screening company that there have been successful pregnancies with embryos selected based on intelligence—might push the movement to take action.

However, there may be common ground across these movements. Funding and investment, via venture capital firms or government research support, is a key lever for reproductive technology. AthenaDAO and its partners have centered women’s leadership and engaged in collaborative funding which has supported niche research on gynecological cancers and polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). It’s an interest that social conservatives may also share. Future for the Family’s strategy was modeled after the President’s Council on Bioethics, an advisory council established by George W. Bush aimed to proactively set boundaries around biotechnology development and use, particularly stem cell research and abortion. This has meant that the Future for the Family coalition’s approach to other types of reproductive health technology is early on in its development: a series of white papers released by the Ethics and Public Policy Center in March 2025 aggressively criticize IVF, while detailing avenues to increase access to endometriosis excision surgery.

These types of important but mundane interventions can be difficult for investors to assess and lack the broader, transformative narratives of, for instance, polygenic embryo screening companies—Orchid frames its goal as to “help everyone have a healthy baby”. This means that despite their potential to reduce women’s suffering and decrease the need for more invasive fertility technology, they often receive less attention and investment from venture and institutional investors. A broad coalition of social conservatives, technologists, and more mainstream liberals collaborating to support oft-neglected reproductive health technology could be a significant step forward towards productive collaboration across these groups.

Movements, organizations, and individuals who are invested in the well-being, status of, and opportunities available to women should take the influence behind these new principles of reproductive technology seriously. Future for the Family represents a nascent – if uneasy – partnership between social conservative policy wonks and technology leaders. The Heritage Foundation is the architect of Project 2025, the blueprint for the current presidential administration, and supporters of Future for the Family from the technology world range from Founders Fund partner and Anduril co-founder Trae Stephens, whose writing is featured as core reading by the coalition, to Audrey Tang, Taiwan’s Cyber Ambassador. And the muddy world of longevity and decentralized science is gaining broader recognition: Pfizer Ventures participated in VitaDAO’s (one of the largest longevity DAO) most recent fundraising round and several longevity charter city projects have launched over the past year.

Ceding this space to movements where the well-being of women is incidental to broader goals would be a mistake, creating either overly strict limits on reproductive technology or prioritizing technologies that do not advance the well-being of women and families. An alternate set of principles could be:

Pro-progress: Innovation and more options for reproduction are good, and safetyism is not.

Anti-suffering: Reproduction often entails significant pain and suffering for women, reducing this should be a priority.

Address broader impact: Reproductive technology will have broader societal consequences, and sometimes costs may be greater than benefits.

We should encourage innovation and be cautious of pro-naturalist arguments that could significantly limit the reproductive options available to women and families, including opposition to widespread IVF use without a clear proposed alternative. This means prioritizing the development of technologies that extend the fertility window and enable women to advance in intensive careers and start families—such as increasing the effectiveness of egg freezing technology and in-vitro maturation. Approaches to reproductive technology development should also recognize and attempt to mitigate the significant amount of pain that both fertility technology and natural reproduction entail for women. This means making the egg retrieval process less uncomfortable and risky and investing in comprehensive research on infertility. Finally, we should also recognize that not every advance in fertility and reproductive technology will be a boon to women and may have significant unintended consequences compared to their benefits. This means remaining skeptical of the need for developing and deploying technologies like some advanced forms of polygenic embryo screening and three-parent embryos. It also means proactively engaging with those—especially women—who prefer the current norms around reproduction, and recognizing the potential loss of meaning that they may experience.

Reproductive technology offers the opportunity to advance women’s material well-being. It also holds the immense potential to usher in a world where women are liberated from the often cruel constraints and consequences of biology. However, this best possible world of reproductive technology is far from a certainty—it is up to us to shape it.

Clicking through Instagram, I am regularly interrupted by ads from egg donation agencies. Less frequently, I receive slightly more personalized emails from fertility clinics in Washington and San Francisco. Although my conversation in Berkeley lingers in the back of my mind, I still haven’t applied.

With gratitude to my interviewees—Laura Minquini at AthenaDAO, Ari Schulman at The New Atlantis, and Courtney Joslin at the R Street Institute—for being so generous with their time and thoughts.

P.S: Eliza has taken her copy of Kernel north of the Arctic circle. If you manage to get any copy of Kernel above 70ºN or (more difficult!) below 70ºS, please let us know! Stay warm out there!

Thanks for reading — if you enjoyed this essay, we’d really appreciate it if you shared or forwarded to a friend!