More chaos, more content. In today’s issue of macrodoses, hear the editorial board’s takes on:

Berkeley AI academics are ditching for the industry gold rush

An aesthetic genealogy of AI micro-sites

New technical approaches to data privacy

Tips to keep on top of Trump’s HHS cuts

What container ships teach us about labor and automation

Please enjoy! —Jasmine

AI Brain Drain?

By jessica dai

The vibes are weird at Berkeley! The EECS PhD program here has always been very industry-cozy, but in the last 3 to 6 months, it feels like something’s changed. I’m nearing the end of my third year in the program, and I’ve been describing it as “that awkward puberty year”—mature enough to have shaped a sense of taste and a more concrete vision, but without yet having had the time to realize that vision completely. For reference, most PhDs in the department take 5-6 years to complete, and for me, it feels exactly right to have these two more years to execute.

So why is it that every other person in my BAIR cohort, it seems, trying to get out of here as quickly as possible? I know at least three who are already working essentially full-time (with graduation delayed only by paperwork hoops to jump through), and many more who are planning to graduate in at most 4 years. And why is it that it seems like every other BAIR faculty (not naming names…) is not only advising startups or collaborating with big labs part-time, but almost entirely absent from Berkeley in favor of their other employment?

There are many simultaneous vibe shifts: for a lot of empirical AI work, it is very true that doing the same work in industry will be far better-resourced and the pay will be many multiples of a grad stipend. And there may be a sense that the froth of 7-figure industry salaries for PhD new grads might be settling soon, a sense that it may be better to go get them while they still exist.

Mostly, I think, there is a sense that the real action is all happening in industry, anyway. Famously, OpenAI and Anthropic these days publish only comically vague “technical” “reports”; perhaps less well-known is that they’ve also all but eliminated real outside academic collaborations. Someone described the feeling to me as a sense of loss, and academics’ actions as corresponding to stages of grief (denial, anger, bargaining…).

On near-term timescales, and within the scope of individual careers, the decisions to leave make a lot of sense. But, in the long run, what this “academic brain drain” means for the AI field, both within and without academia proper, is unclear. As a discipline, it’s probably true that CS was already unsustainably bloated (just look at cohort sizes in, say, chemistry or statistics), and maybe the shrinking of the (academic) field is merely a correction of that bubble. But the situation does, still, beg the question of what the point of a PhD is—newly-admitted students, I hear, are now challenging their would-be advisors on this question—or what the role of academic research, as opposed to closed-door R&D, should be. Answering those questions would be a whole other essay…. So if you work in AI in any capacity and are interested in chatting, email me!!!

A Site for Every Soliloquy

By Jasmine Sun

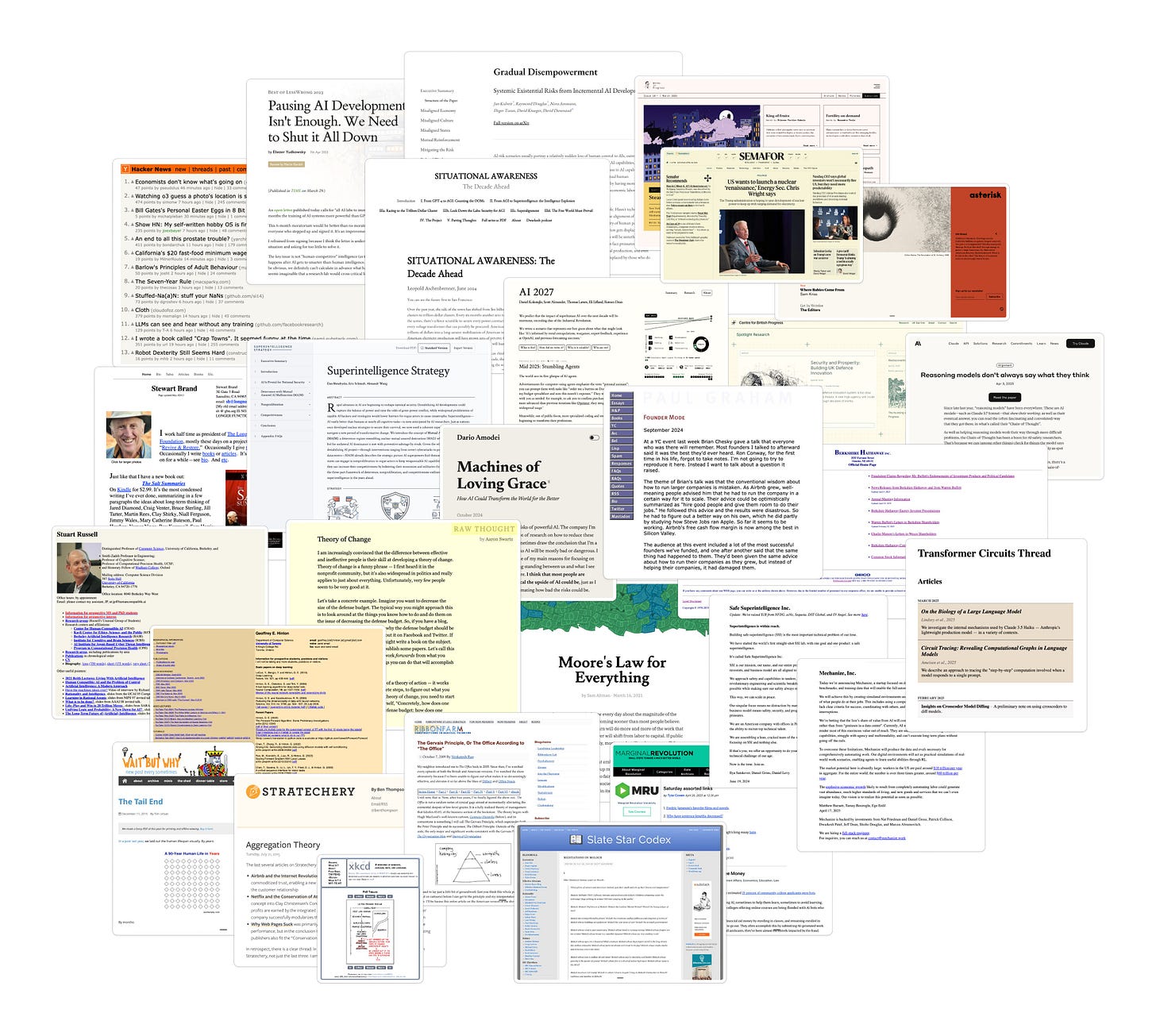

It’s become a meme that every AI essay trying to Do Something™ in the world must launch with its own custom-built microsite, usually with a serif font, minimal design, high-minded title, and off-white background. Situational Awareness, AI 2027, Superintelligence Strategy, Gradual Disempowerment, The Intelligence Curse. Their designs each suggest that an ordinary Substack post would be too unserious—what really defines an idea’s quality is striking the perfect balance of “trying really hard to seem like I’m not trying hard,” like the “no-makeup makeup” of thinkboi blogs.

The more I look at these new sites, the more familiar they seem. The old-style serifs and thin rectangular boxes on AI 2027 reminded me of OG rat forum LessWrong. Several abundance-adjacent nonprofits all use the UK-based design studio And-Now. The website for automate-all-jobs startup Mechanize is a whole-cloth ripoff (or homage) of Ilya Sutskever’s notoriously hermetic SSI, and both are LARPing the IDGAF aesthetic tradition pioneered by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, which hasn’t redesigned its “WEB page” of purple hyperlinks since 1999. And while shades of orange aren’t particularly popular for decorating, well, most anything else, the palette has been a fixture of tenured-professor-sites and YC-adjacent hacker blogs since the mid-aughts.

These Einsteins would probably prefer us to think that they’re all substance and no style. The less CSS the better; not a gradient in sight. But their design choices are no accident—you can see an organization’s idealized intellectual forefathers in their muted colors and bookish fonts. It’s signaling all the way down.

Datapoints are all you need

Recently, I came across a paper for DataMap, “A Portable Application for Visualizing High-Dimensional Data.” One of DataMap’s key features is that it's privacy-preserving. Typically, creating a meaningful plot requires some familiarity with your dataset, but researchers are suggesting that meaningful insights can be extracted without even looking at the data—that the principal components of a demography can be gleaned at a script's run.

This matters because many “encrypted” services boast that they never access user data—great news if you're confessing secrets to Claude or outsourcing your taxes. But decision-makers face a black box: ‘hard’ evidence backed by opaque, unsupervised algorithms.

DataMap is not alone, systems like it are becoming more entrenched in world (data) order. In 2020, the U.S. Census Bureau implemented differential privacy—adding controlled noise to the data—to safeguard individual data in the annual census. Google, LinkedIn, and Microsoft have all also deployed their own differentially ‘private’ data systems.

In December 2024, Anthropic released Clio, “a system for privacy-preserving insights into real-world AI use. But their methodology raises questions: for instance, they take an “empirically validated approach to privacy,” where a model gives a score on a five-point scale based on the sensitivity of data points in a raw dataset.

However, simply turning off data sharing for your chat history doesn’t necessarily guarantee privacy. While tools like Clio feel like steps in the right direction, there’s no way to fact-check the details of their proposed methods and ‘objective findings’ from researchers working with the companies whose products they’re tasked to evaluate feels specious.

Open-source presents itself as a panacea, but it seems unlikely we’ll get the source code for tools like Clio anytime soon. Third-party organizations working on privacy-enhancing tech like OpenMined could be a stopgap. But even with open-source, only individuals who care to look can understand how they work.

Lastly, even with access to ‘visible’ datasets, researchers are operating blindly—relying on summary statistics that are often misleading and outdated methodologies that peer reviewers rarely bother to fact-check. After all, summaries don’t claim to tell the full story.

Death by a Thousand Cuts

When it comes to changes in public health administration, major news outlets are waiting for the budget resolution to pass in Congress to find out whether Medicaid coverage will decrease. But the executive branch has a lot of power to legally create process blockers, reorganize agencies, and withhold funding for public health programs and grants right now.

To Jasmine’s point that “reality has a surprising amount of detail,” Inside Medicine is a solid Substack tracking a lot of the specific changes inside of the Department of Health and Human Services. It’s helped me get a sense of how much the government actually does and how many banal ways an administration can block progress and create serious public health risks that have nothing to do with how much you pay to see a doctor.

A Tribute To The Global Supply Chain (1950-2025)

When I read Marc Levinson’s The Box, a sprawling history of the birth of the container ship, back in February, I was not expecting it to be quite as geopolitically relevant as it has ended up being during this moment of tariffs, shipping freight declines, and other such crack-ups of the global economic order. The past two months have lent the book a certain elegiac mood—Levinson starts his story in the aftermath of World War II, sketching out how the concept of “shipping things in big boxes” went from a get-rich scheme from entrepreneurs on the Atlantic seaboard to the governing principle of the entire supply chain. Ozymandian!

Yet as much as The Box is a story about how the economy writ large became global, it’s also a story about how local economies and structures of labor became highly automated. While no one would accuse Levinson of being a Marxist scholar or a union propagandist, he gets deep into the differing approaches that the factions within capital and labor took to the impending wave of automation. It’s a set of stories that feel doubly relevant now, as attempts to build “full automation of the economy” get more attention. Perhaps most interesting is the case of the ILWU, to this day the more radical of America’s two longshoremen unions. Where the East Coast-centered ILA fought automation unequivocally, the West Coast’s ILWU, led by the Communist Party-affiliated Harry Bridges for forty years, wound up taking a different tact.

As port automation became more and more imminent in the late 1950s and 1960s, Bridges steered the ILWU towards a path of compromise and adaptation, saying “Those guys who think we can go on holding back mechanization are still back in the thirties, fighting the fight we won way back then.” Over the course of a half decade of negotiations, the ILWU brokered an agreement with capital that preserved wages and jobs while allowing for labor-saving technology to be implemented, maintaining labor’s power while reducing workplace injuries. As we stare down attempts at automation far more wide-reaching than containerization, we ought consider a wider range of historical precedents—not just Luddites and their descendants, but the full and messy picture of how labor has negotiated its own automation.

We’re out here sensemaking. If you’re interested in more historically and politically informed tech coverage, sign up below:

Ironically, "reality has a surprising amount of detail" actually came out of LessWrong in 2017: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/hBPkwBZoMwRdcsCoo/reality-has-a-surprising-amount-of-detail

new project sites just need to enter the web brutalism era and the cycle will reset