Reboot Macrodoses are an informal ~weekly dump of what our editorial board is reading, watching, playing, seeing online, thinking about, or otherwise experiencing. It includes mini-essays, links, pictures, plus perspectives from our beautiful brilliant readers—if you’d like to publish a 250-word Letter to the Editor about our previous essays, you can now do so here.

In today’s issue of macrodoses, we have:

Our take on the news from OpenAI

A response to Kyle Chayka’s Filterworld

Yearning for YouTube of yore

The “worldbuilding turn” in tech and beyond

Our reflections on Fredric Jameson’s work

Microdoses, to balance your portion size!

Hope you enjoy!

—Shira

OpenAI News

Recent developments at OpenAI continue to confirm our expectations.

Filtered

by Jacob Kuppermann

Have you heard about algorithms? Kyle Chayka would like you to be aware of them. He would like you to recognize them in their many guises: the algorithm as globalizer, gatekeeper, girlboss. For Chayka, algorithms are be all and end all of contemporary digitized culture, an internetish malaise spilling over into the real world, a haze that engulfs all of the unique quirks of culture leaving nothing but a hyper-optimized, perfectly instagrammable mass. This is, roughly, the thesis of his book Filterworld, published earlier this year. It’s also the thesis of essentially every column he’s written over the past four years at the New Yorker. There is no shame, of course, in having a beat, but Chayka’s argument rests on perhaps too-well-trodden ground. Chayka did write some of the earliest and canniest essays about how algorithmic incentives have shaped the physical environment of coffeeshops, AirBnBs, and other millennial lifestyle enclosures, but his analysis in Filterworld rarely goes beyond what those takes achieved nearly a decade ago. Instead, the book relies on a clutch of pre-digested tech-crit shout outs — the first few pages inflict upon the reader references to the Mechanical Turk, Cybersyn, the Communist Manifesto’s opening lines, and (maybe worst of all) “the medium is the message.”

I’ve not yet given up on the potential of tech criticism centered on the power of algorithms — we’ve published some of that at Reboot! But Chayka’s approach is a strangely provincial one, returning again and again to the same algorithmically optimized coffee shops and the lives of hyper-aestheticized influencers. There’s little in the book about the stranger edges of online culture, something which points to the key irony/failure/tragedy of the book. In order to make his own arguments about the hegemony of the algorithm land seem more compelling, he seems to do some of its homogenizing work for it. Filterworld paints a picture of the web that rarely goes beyond the most prominent parts of Instagram and Twitter — there is little about how filtering has affected, say, niche fandom or hobbyist spaces, or even what parts of the internet have evaded the filter of the algorithm. This dynamic even shows up in Chayka’s own writing, which seems optimized for social media, composed of screenshottable, sharable paragraphs on phenomena that his audience (myself included!) already knows about. As we’re always saying here, we need a better tech criticism — by subsuming our own takes to the same hard filtering that has affected so many online and offline spaces, we do ourselves a disservice.

YouTube Nostalgia

by Shira Abramovich

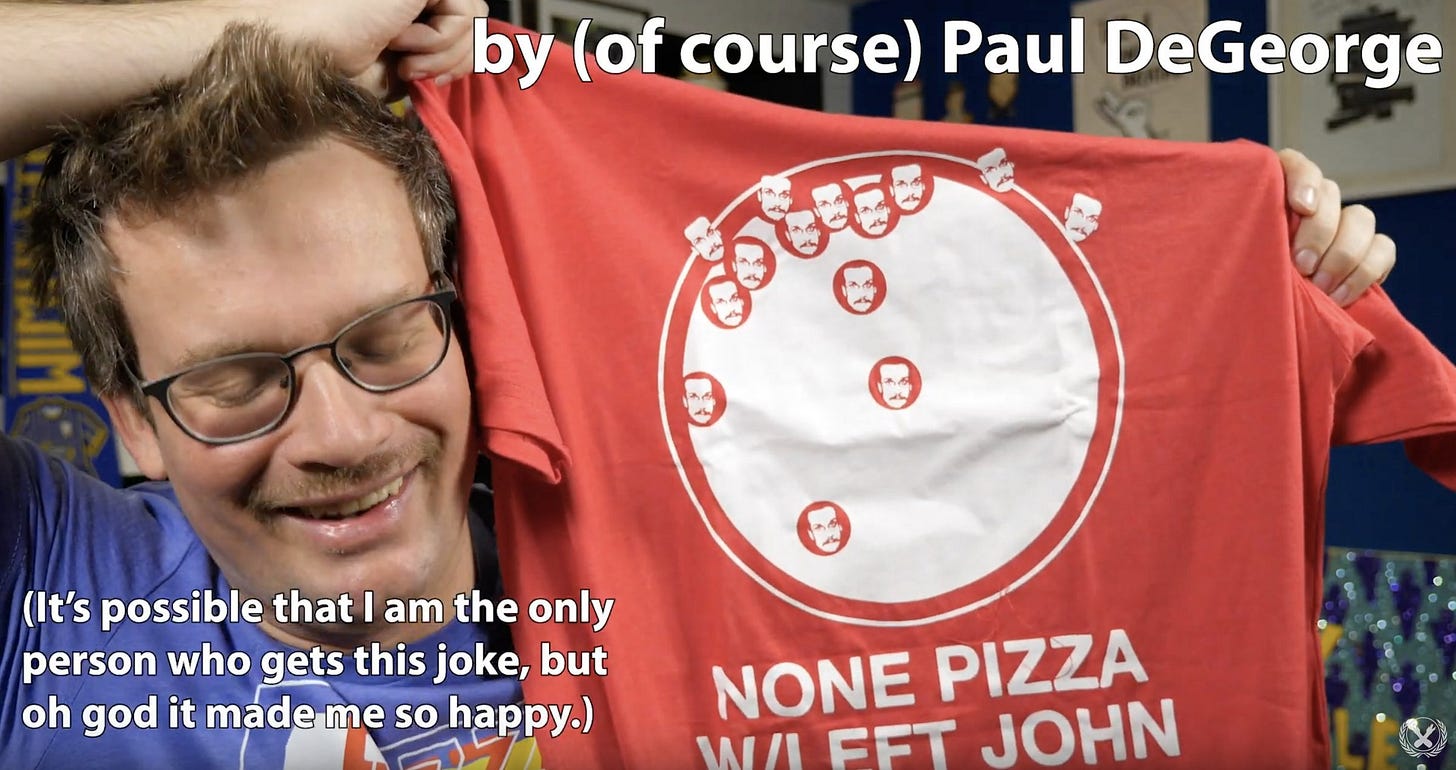

It’s Pizzamas.

For those not in the know (i.e., those not cringe enough as teens to follow Vlogbrothers, nor to keep following them well into adulthood), Pizzamas is the annual vlog-tradition-slash-fundraising-marathon-slash-meme-slash-nostalgia-festival that occurs yearly in September or October on the Vlogbrothers YouTube channel. For two weeks, Hank and John Green commemorate “Pizza John,” a meme of a mustachioed John Green and his love of pizza, by making videos daily, as they did during the channel’s first year in 2007—an exercise in nostalgia, and an ode to the early days of YouTube.

I’ve been around for many a Pizzamas—I’ve been watching the channel since 2010, three years after it started, and I remember being online as its subscriber count ticked up to a million for the first time in 2013. As the dynamics of YouTube have shifted to a mix of shorts and longer, less-frequent, higher-effort videos, the Vlogbrothers channel—with its earnest comments, four-minute videos, and strange but enduring traditions—has come to feel like a time capsule. Pizzamas intensifies that feeling. The merch that gets sold during these two weeks often refers also to earlier versions of Internet culture, such as the None Pizza with Left John shirt that appeared in 2019—the first time I was conscious of remembering an old, popular meme that had fallen off and been forgotten.

This year, Hank and John have focused some of their daily videos on memes from the early social Internet, which were made in a context that doesn’t exist anymore. Even if these memes predate my time online by a few years, they’ve made me think a lot about how referential the early Internet was—and how many of these references are lost as communities die or sites go offline. It’s been odd to watch my Internet memories become literal Internet history, a feeling which I’m sure will only intensify with time.

Worldbuilding for Hire

by Hamidah Oderinwale

In an interview with Embedded, Jasmine calls for more “software pitchforks,” emphasizing that when we aim to improve the future, merely criticizing technology isn't enough; we must also voice our aspirations. We can certainly critique what already exists, but we must also define what it is that we want. We need rigorous optimism. For this reason, more artists, writers, and humanities folk should embrace the role of a “technologist”—and vice versa.

Government ideates what can be, unburdened by what has been. Generating these ideas, however, isn’t the easiest of tasks. The U.S. government contracts worldbuilders for hire, to do just that: world-build. The Sigma Forum (h/t Kelvin Yu) is a think tank staffed by a group of impressive scientists-turned-sci-fi visionaries, offering “futurism consulting” services, working as technical dreamers for hire. Asimov Press, the biology-focused, science progress magazine has fiction as a staple in their publication: crafting fictional, but uber-realistic fictional universes with AI-led scientific discovery and cities afflicted by zoonotic disease.

More on the topic of science-fiction writers and their influence: Perhaps, the most notable is Arthur C. Clarke and his work, the Wireless World, which is credited for inspiring NASA to develop the modern satellite. Likewise, in a video on the S3 YouTube channel, Jason Carman interviews John Gedmark, the founder of Astranis: the satellite technology upstart. In the interview, Gedmark names Arthur C. Clarke as inspiration for founding the Starlink rival.

In a parallel vein, Nat Friedman is breaking free from the cast of typical tech investors. Recently, he made a call for an intern to investigate a theory about the Shroud of Turin (as mentioned in Macrodoses 2).

With this all, I’m reminded that “moonshots” can be more than just products; they can be narratives too. Well-crafted narratives have served as catalysts for many of the engineering feats we marvel at today. And the humanities’ influence on invention is sold far too short—if world-building is a duty and we recognize its two axes: engineering their visions of the future, and artists who define these visions.

—

(10/13/2024) Update: I came across the Science & Entertainment Exchange through Casey Handmer’s blog. They’re a National Academy of Sciences program that connects entertainment professionals with scientists to advise on films and TV.

Meditating on the Impossible

by Hannah Scott

Since hearing the news of Fredric Jameson’s passing this past weekend, I’ve been revisiting Archaeologies of the Future, the cultural critic’s exacting dissection of science fiction and its many strains of Utopianism. Jameson carefully maps the conceptual contours of Utopia, speciating its various literary incarnations through analyses of works like H.G. Wells’s Time Machine and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Lathe of Heaven. In doing so, he unspools a strikingly honest version of utopian imagination, one that admits the apparent impossibility of realizing alternatives to the present — both in practice and in fiction — while rescuing the sense of historical possibility that utopian thinking allows. For Jameson, the liberatory potential of science fictional Utopias lies not in visions of new technology, but rather in the fact that it frees us to imagine a break with the past:

“Utopia thus now better expresses our relationship to a genuinely political future than any current program of action, where we are for the moment only at the stage of massive protests and demonstrations, without any conception of how a globalized transformation might then proceed. But at this same time, Utopia also serves a vital political function today which goes well beyond mere ideological expression or replication. The formal flaw — how to articulate the Utopian break in such a way that it is transformed into a practical-political transition — now becomes a rhetorical and political strength in that it forces us precisely to concentrate on the break itself: a meditation on the impossible, on the unrealizable in its own right” (232-3).

In Jameson’s self-described “anti-anti-Utopianism” I find a refreshing, roundabout route to optimism toward thinking and writing about those possible futures we wish to see but that our historical and contemporary conditions disallow. Beyond the hollow, packaged styles of Utopian thought — I’m thinking of “speculative thinking” and “futurism” — that often get drunk on the general vibe of ossified sci-fi aesthetics and the grand arc of technological progress, a more sober Utopianism is possible, and for that we owe much to Fredric Jameson.

🌀 microdoses

How do we find cool links on today’s Internet?

More Sunday reading: code poetry!

Support more of tech’s weird, wonderful, and sincere by subscribing to Reboot:

Worldbuilding for Hire: fascinating, convincing, points to new rabbit holes which is always a plus!