A few months ago, someone tweeted about an AI founder’s LinkedIn account; it belonged to George “geohot” Hotz, who in 2007 became the first person to remove the SIM lock on an iPhone. The name, which apparently didn’t ring a bell to most, reminded me to write my own tribute to the lost art of iOS jailbreaking.

P.S. Bay Area readers—don’t forget to get your tickets for Reboot Community Day!

Out of the Sandbox

By Tianyu Fang

At the age of ten, I received my first Apple device: a second-generation iPod Touch. In numbers that don’t mean anything anymore, it’d come with the iOS version 3.1.3, and the latest firmware it could upgrade to was iOS 4.2.1. It didn’t have a camera, you couldn’t set custom wallpapers for the Home Screen, there was no Notification Center or a remotely functional filesystem, and multitasking between apps had only recently been made possible.

I was in elementary school back then, and I was desperately hoping to do more with my iPod. I’d seen screenshots of iOS with customized typefaces, icons, and widgets on social media and forums; I wanted to replicate these modifications on my own. That was how I discovered jailbreaking. I spent many hours on forums trying to jailbreak my iPod—removing Apple’s software restrictions, typically by kernel patches and other exploits, and obtaining root access.

Cydia, the third-party package manager that predated the App Store, felt like a weird box of forbidden fruits where I experimented with widgets and apps that occasionally caused glitches and rebooted my iPod back to Safe Mode. I had a lot of fun with it, playing around with WinterBoard to customize the user interface; my favorite was SBSettings, which was likely the inspiration for Apple’s own Control Center. Among other widgets I can remember was iKeywi, a keyboard that offered an extra row of numerals.

Jailbreaking was a form of everyday hacking. iOS’s software permissions lagged behind the capabilities of the Apple hardware, and jailbreaking allowed for a radical imagination of what the iPhone couldn’t do straight out of the box. The unknown worlds outside the iOS sandbox, as it occurred to me, hid new, exhilarating possibilities—what could I do with my device that I hadn’t yet explored?

The world of jailbreaking was full of blurred lines. On the one hand, jailbreaking was an underground practice, not to be acknowledged by the manufacturer, which voided the warranty of jailbroken devices. It required a bit of technical skill and the willpower to refrain from upgrading the firmware (which would trigger a boot loop).

Yet on the other hand, jailbreaking was immensely common, if not almost essential, in China, where I lived: on Taobao, where cheaper, parallel-imported iPhone units went to market, vendors would offer a small fee to jailbreak your device beforehand. The earliest generation of the iPhone didn’t come with good multilingual support, and when it did, third-party apps were often in English only; you couldn’t install community translations without jailbreaking. The imported units were often locked to their original carriers. No one was buying apps on iTunes, either: paying for software had barely crossed anyone’s mind, and few of us owned the kind of international credit card that was required for a 99-cent copy of Doodle Jump. Jailbreaking also allowed users to access features that were, even then, common among other Chinese phones: one popular tweak was KuaiDial, which showed the origin city of every phone call and blocked numbers that were marked spam in public databases.

In my Beijing elementary school, I quietly got away with my shenanigans by helping teachers jailbreak their iPhones. I skipped classes to fix school computers and helped the staff with technical tasks to earn some extra screen time. As I played with tweaks and apps on my device, I became subversive at school. Instead of paying attention to class, I devoured novels by Zheng Yuanjie and Han Han: the former a children’s book author who thought teachers were corrupt and homeschooled his child, and the latter, a race car driver turned blogger who openly discussed government scandals and ridiculed state authorities in his national bestsellers. I also became enthralled with Luo Yonghao, a former English teacher who once ran Bullog, an uncensored blogging site, before starting a smartphone company that designed custom ROMs and threatened to rival Apple.

Back in the early 2010s, nothing in China was truly authentic—or, for what it’s worth, strictly legal. The post-Mao reform itself had opened China’s borders and turned the nation into an export-oriented electronics factory—in the process, the entrepreneurs took actions before the government wrote proper laws. One side effect was the burgeoning DIY culture, especially casual hacking, customization, and piracy. In Beijing, everyone knew someone who could go to the electronics markets in Zhongguancun and build a PC from scratch. When we couldn’t afford something we’d go for a cheaper shanzhai (copycat) substitute. In markets and on the internet you could find thousands of modified copies of Microsoft Windows XP Service Pack 3, and while every printer shop in your neighborhood had the full Adobe suite, no one had paid for a legit license.

In unexpected ways, iPhone jailbreaking offered a window to political subversiveness. Apple’s case against jailbreaking, and the justification for the low customizability of its products, was security. It’s unsafe to modify the firmware. Your warranty will be voided, and your phone might turn into a brick. No one will be out there to help you; you’re on your own. In the walled garden, to exploit loopholes is to expose oneself to the dangers of the outside world. On discussion boards and social media platforms I became conscious of the encroaching apparatus of internet censorship. To the paternalistic Chinese state, to discuss, to know, and to participate—outside the government’s purview and beyond its protection—was rendered dangerous. It would hinder political stability, the backbone of a fast-growing economy.

Meanwhile, the Chinese jailbreaking community relied heavily on knowledge from abroad. It reposted content from Twitter, which had been blocked by the Chinese government in 2009, and US blogs such as iDownloadBlog. As such, tips on circumventing the Great Firewall circulated rather openly on technical discussion boards.

Inadvertently, jailbreaking opened the way to more jailbreaking. The VPNs I used to download iOS firmware and read blogs opened up another world for me. In 2011, the Arab Spring was in its heyday, and social networks were seen as the vehicle towards democratization. In Beijing, a small crowd gathered outside the McDonald’s on Wangfujing shopping street, as a few days earlier internet posters had called for a “jasmine revolution” (it failed to gain much traction). The writer Liu Xiaobo, who’d drafted a democratic charter for China, received the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize while in detention. The artist Ai Weiwei, whose passport was confiscated by the government, placed a bouquet every morning in the bicycle basket outside his compound, not too far away from where I lived, and posted a photo to Instagram. In the next few years, on the internet outside China’s Great Firewall, I followed democracy activists and dissidents in exile, read their works, and explored the histories outside officially sanctioned narratives. My technical interest in jailbreaking, in other words, shaped the political consciousness of my teenage years: to test edge cases, explore vulnerabilities, and challenge authority.

When I was 15, I left China for the United States. In Massachusetts, I became skeptical of the flavor of liberalism that Chinese dissidents that I followed in the early 2010s aspired after. My lived experience in the US contrasted with their romanticization of the West, idealization of the free market, and whitewashing of injustices in liberal-democratic societies; I lamented their inadequate care for China’s class inequality and urban-rural gaps, if not their naïve faith in Western interventionism for political change in China. Further to my dismay, in 2016 many Chinese liberals turned to Trump and the far-right. On the other hand, in sharp contrast to the rebelliousness of our parents’ generation who came of age in the 1980s and 1990s, the young Chinese of my generation were increasingly viewed as staunch defenders of the state, having reaped so much economic benefit from its heavy-handed rule. The Chinese state has an increasingly stringent control of the internet, and it is anxious about the threat of emerging technology, like AI, to its political stability.

I haven’t used a jailbroken device since 2014. Because why would I? While years ago the jailbreak community had to bootstrap their own solutions, today Apple has made the iPhone much more customizable. It has continuously incorporated community-designed features. Functionalities that we now take for granted—the Control Center, dynamic wallpapers, predictive texts—emerged in the jailbreak world before they were built in. (Don’t forget: Cydia had existed before Apple permitted third-party apps.) There are still jailbreak tools around; the iPhone is no less hackable. It just seemed much easier to use it as-is.

Maybe there’s something worth preserving in the practice of everyday hacking, as a quest for individual agency, alternative possibilities, and extended boundaries. In the US, too, we’re at an impasse: the deadlock in electoral politics, the encroachment of corporate power, and the powerlessness of communities. It almost feels like we’re embedded in inert technological prisons that resist deviance, creativity, and change. Under surveillance capitalism, we voluntarily surrender our most intimate data just to participate in society. We buy fully assembled electronic devices that we can’t modify or repair. In the near future, the hardware in our hands might be scrap metal without being connected to a large language model that we have no control over—not even if we asked the chatbot to “ignore all previous instructions.”

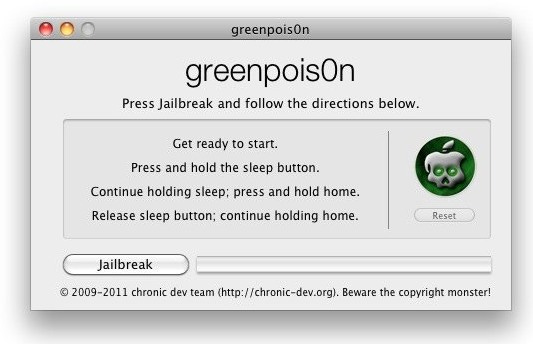

I can never forget the exhilaration I felt when I jailbroke my first iPod: it was, after all, my first act of adolescent defiance. Cydia, the package installer, was named after cydia pomonella, the codling moth that infects apples; the logo of redsn0w features a pineapple inmate on the run. For my first iPod touch, I had to use greenpois0n, which had a skull on its icon. I wasn’t sure if I was going to turn it into a brick, but I clicked “jailbreak” anyway. I felt free.

Tianyu Fang is an editor of Reboot. He’s a MacArthur Tech & Democracy Fellow at New America. Previously, he was the founding intern of Chaoyang Trap, a newsletter about life on the Chinese internet.

Reboot publishes essays on tech, humanity, and power every week. If you want to keep up with the community, subscribe below ⚡️

microdoses

Client did not pay? Add a few lines of JavaScript code.

The Long Season (2022), which is a story about the 1990s decollectivization in the northeastern China, is one of the best Chinese television shows in the last ten years. Now there’s a version on YouTube with English subtitles.

This tweet by Omar Rizwan:

closing note

What are some “forgotten” technologies like jailbreaking? Want to write about it? Send me a pitch: tianyu at joinreboot.org.

—Tian & Reboot team

Great post. There was something so great about that period; I remember hacking my first android phone (first and only), so I could install custom versions of the OS. Felt like a proper nerd. Always got into torrents or hacking copies of software back then cause I couldn’t afford shit.

Simpler times.

Thanks for your window into the computing and software world of China before the dastardly regulators caught up, and for pointing out the western surveillance state.

I jailbroke an iPod Touch just to learn. It was great fun.

Decentralize everything!!!😎