📏 How To Build A Mayan Keyboard

A Conversation with Nic Sahler of the Codical Mayan project on indigenous language preservation

Kernel Magazine Issue 5 is out now! In case you missed it, you can read the editor’s note here. We’re releasing a few pieces this week as previews — for the rest, join us at the launch in SF or order your copy of the magazine now!

—Jacob Sujin Kuppermann

Allison Tielking is a software engineer, language enthusiast, and city planner (to be!) based in Brooklyn, NY.

Nic Sahler is a design technologist based in Brooklyn, NY.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

📏 How to Build a Mayan Keyboard

Interview and introduction by Allison Tielking

In the late 20th century, in the early days of computing, many writing systems – from Latin to Chinese – went through a process of forced simplification. Languages with the greatest complexity, such as Chinese and Arabic, underwent the greatest scrutiny in order to fit their complex forms into limited spaces with small memory footprints. Around the same time, Mayan, a 3,000 year old language, experienced a rebirth that led to a nearly complete, revived understanding of its writing system.

I met technologist and Mayanist Nic Sahler at Living Skin, a community space, library, and gallery in Bushwick. In response to the hyper-creation of our digital age, Living Skin is carving out new systems of human knowledge and art preservation while paying respects to the information collection systems of ancient societies. When I saw some Arabic-Indic numerals flash on Nic’s phone screen, we got to talking about his involvement in the Codical Mayan project, whose goal is to encode the Mayan writing system into Unicode. The team is doing this work to simultaneously preserve the artifacts and stories of the past and empower the Maya people with free tools to learn and spread their written language.

On a Sunday afternoon, Nic and I sat down to talk more about his work on indigenous language preservation and digital humanities.

Allison Tielking: What initially sparked your interest in indigenous language preservation?

Nic Sahler: I have indigenous roots in Puerto Rico; my curiosity started at a young age but largely became more focused around 2018. I started aggregating and cataloguing indigenous Puerto Rican dictionaries and encyclopedias to survey how much indigenous language still exists, and how it influences Puerto Rican culture. I recorded around 2,000 words and found that the largest influences live on in food, place-names, and slang. The influence of indigenous Puerto Rican language persists in English and Spanish, in words like barbecue, canoe, and hurricane. Even Tagalog has words from Taíno that are no longer used in Puerto Rico.

I read a book of interviews with a Taíno chief (or Cacique) in Cuba, who is the only (currently known) monarchic leader of a Taíno tribe, with his roots being recorded several hundred years back. Before COVID, Puerto Ricans began visiting this tribe, sharing information, even hosting a conference. When I hit dead ends there (though it’s still a very open and slowly progressing field), my curiosity turned towards Taíno’s closest living sister languages: Lokono and Garifuna, which are languages with lots of cognates, or common similar words. That’s how I arrived at Mayan.

Can you tell me more about Taíno and its sister languages?

The term “Taíno” is somewhat controversial. It’s not offensive, but it wasn’t necessarily the name the island’s indigenous people used for themselves. The phrase “Taíno” is believed to have meant something like “We are good people,” said to the Spanish upon first contact. Today, it’s considered more of an archaeological term than an anthropological one, used to describe the theoretical elements of indigenous Caribbean culture. The culture it refers to spans from the Florida Keys all the way through the Dominican Republic and Haiti to the very end of Cuba, where it’s debated whether a different tribe (theorized to have been influenced by Maya people) resided.

This region historically had two primary language families: Carib and Arawakan. They’re mutually unintelligible. It was a cultural custom for men to only speak one language, while women spoke the other. This custom obscured a lot of modern research on the culture, making it hard to pin down which words in the world had true Taíno origin.

What brought you from researching Taíno to the Codical Mayan project?

I found some similarities between Arawakan and Mayan languages interesting. They’re from different language families, but they have some shared vocabulary. I also marveled at how Caribbean culture and food are closer to Mayan than to Mexico proper. There are even other connections — a traditional ball game played in Puerto Rico is an almost identical (but simplified) version of the Mayan ball game Pok Ta Pok. People don’t understand this connection, but their geographic proximity could be a big part of it, possibly due to trade.

While exploring, I found the Codical Mayan project, which was initially focused on cataloguing Mayan texts. I was a Machine Learning Engineer at Squarespace at the time, so I emailed the project lead, Carlos, and offered to use machine learning for Mayan character recognition. However, due to limited text availability, we did not get far. Because of this, the project eventually expanded to focus on broader Mayan cataloguing and typography work, which could enable more advances in the future.

Can you give me some background on the Mayan writing system and language?

The Mayan script is a writing system for proto-Mayan, the ancestor of about 30 dialects that are today spoken by millions of people across Guatemala and Mexico. The writing system combines logographic (symbols which represent words) and syllabic (symbols which represent syllables) symbols. Though primarily used by priests and nobility, some colloquial knowledge persisted among commoners.

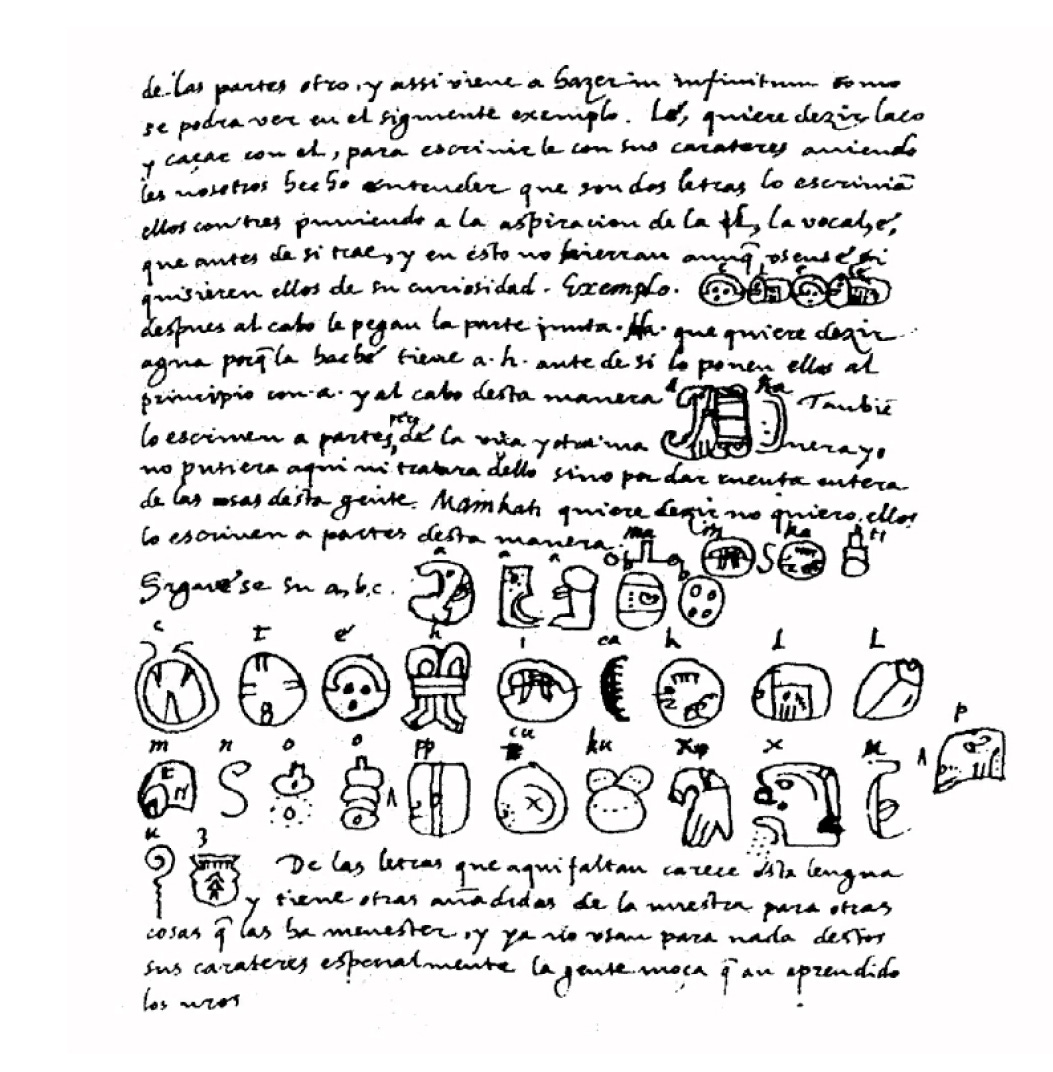

In 1562, Spanish friar Diego de Landa led a religious campaign, destroying 27 Maya codices containing knowledge of Maya religion and civilization. Legend has it that the four remaining manuscripts were exfiltrated to Europe. Today, they are known as the Dresden, Madrid, Paris and Grolier codices. The Dresden codex ended up in Russia after World War II, where the Russian linguist Yuri Knorozov made breakthroughs in deciphering it using a small note that gave him 10 characters to work with.

Since Mayan people still know colloquial characters and speak the language, they have made major advances in the study of the Mayan writing system following Knorozov’s 1960s research.

Where does the Codical Mayan project work fit in?

The project’s main goal is to make Mayan an available writing system on every computer. This requires two things: encoding the Mayan writing system into Unicode and developing a font and keyboard. Once those goals are complete, we aim to use those pieces to catalogue Mayan codices, remaining artifacts like writing on temple walls and ancient Maya belongings, and folk stories that are not yet written down. A major goal is to interview people in the Yucatan, recording their stories using the traditional writing system.

At the same time, we want to enable people to type in Mayan using the new Unicode codepoints. Currently, Mayan is written using Latin letters–like we do in English–but this is insufficient and removes a lot of cultural context. We’re working on a keyboard which lets people use a system similar to Pinyin which would convert the Latin alphabet and phonetics into Mayan.

Turning Mayan into Unicode makes it machine-readable, a series of numbers instead of just a photo, so you’ll be able to type and quickly repurpose it for new artifacts that use the same system.

After finishing this font stuff, what we really want to do is enable Mayan people to use it on their own. We might go to Campeche for the Mayan Cultural Researchers Conference next year, where we can hand people tools and teach them how to use them. Like, look, you can use Photoshop in Mayan now!

We don’t know if what we’re making is a better system yet. There are decisions we’ll make on how it gets encoded that might be wrong, so it will be important to get feedback from people who grew up more in the culture. We’re not trying to dictate how people use it, but instead provide a free, open source tool. Putting Mayan in Unicode means that every computer will ship with the Mayan writing system, like how every computer has Chinese, or even Egyptian.

After your initial machine learning work didn’t pan out, what did you end up working on for the Codical Mayan project?

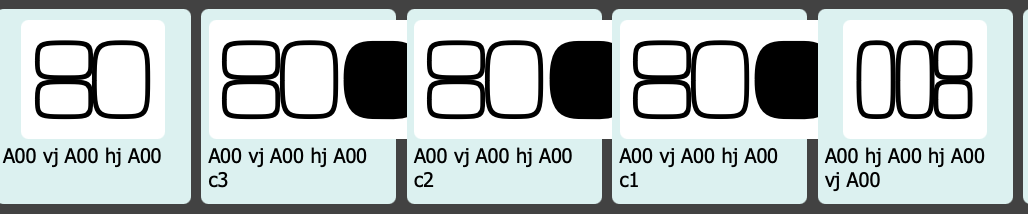

The head researcher and founder of the project, Carlos, built a unique grouping system to categorize Mayan characters. This system governs the order we are developing the Mayan font in. Carlos submitted a series of Unicode Proposals which encoded this system, consolidated variations of characters, and gave us a roadmap to get Mayan onto every device. Unicode is a consortium which dictates which emoji and fonts work on your phone (and nearly every computer!) Every character in every language you can read on a computer (along with emoji and some symbols), exists in Unicode as a mapping from a number to a character. We’re trying to do that for Mayan, so we had to submit a proposal and go through many iterations.

While Carlos fine-tuned the proposal, I built out an underlying system to store our research. I first created a database for cataloging Mayan characters, which our team uses to organize Mayan as a knowledge graph, which is then used to map it to Unicode code points. We did some statistics on the database and pared it down into what symbols were isolated characters with independent meaning. Then, we submitted a proposal with all the characters to put into a font, along with how the characters were going to mesh together.

After submitting the proposal I started building a system of tools. The font is being designed using FontLab. The team broke up the characters by grouping and tackled different groups. We meet up weekly to compare our designs, typography work, and structure and keep in sync. I also created something like Google Docs for Mayan, so our team could communicate with each other, leaving notes directly on different characters that we’re working on, overlaid on Mayan artifacts and codices. As an extension, we’re going to make an overlay version of my Mayan Google Docs tool so you can overlay the actual font, making the artifacts searchable for characters and concepts.

One teammate, Andrew, is working on a low-level system for treating Mayan Quadrats (the sub-grid in which glyphs combine together) like font ligatures, allowing a series of codepoints to render out into a full glyph. I started aiding in this work recently.

So far, we’ve completed just a small subset of characters, maybe 300 out of 1,500 known characters. We finished our second milestone out of six, and it took about 3 months per milestone. The next phase is cataloguing more of the codices and hand labeling more characters.

What motivates you to work on this project?

Maya culture is maybe one of the most well preserved native cultures. There are many places, like where I’m from in Puerto Rico, where indigenous culture is a bit mysterious. While everyone has some connection to their indigenous roots, the culture underwent several heavy colonial eras, genocides, and cultural mixing, so it’s not well catalogued. Because Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic were the point of first contact for Spaniards (and Europe at large), its original culture was regularly paved over by generations of change, with US occupation doing some of the most extensive damage during the industrial era. Being able to help preserve such a strong and extant culture and see it thrive is a breath of fresh air, and something I believe my ancestors, both recent and ancient, would appreciate. It feels like I am serving them by serving the Maya people. Also the Mayan writing system is cool in its own right.

How do you see the role of technology evolving in the preservation and revitalization of indigenous languages?

There is a known hunger among Maya people to learn, and they now have classes where they can learn to write traditional characters. Currently, a lot of classwork is done on paper, but these tools could enable people to build more dictionaries, create their own textbooks, and share them more easily with one another.

Through my initial dictionary building work, I got involved with a different group called Natives in Tech. Their leader at the time, Adam Recvlohe, built a dictionary for Muscogee, a tribe originally from the American Southeast. He also had to aggregate from many sources, some of which he had to paraphrase because they were published and copyrighted—making it hard to document his own language. We’re avoiding this by not taking ownership over the language—it is an effort involving people from the culture (both Carlos and the people we intend to serve) which aims to increase its availability to indigenous people, not decrease or gate-keep it.

To close, do you have any advice/recommendations for people reading this?

I’ve seen that a technical bottleneck exists in this kind of work. If you really care about a topic or research project, reach out. Show that you have something to add or that you really want to learn. I didn’t go to college, so this was my first foray into academic research. The reason I felt comfortable reaching out to the team was because I had heard so much from academic friends that they just emailed a cool professor and ended up getting a PhD under them. My interests and passions were in line with the team, and we shared a common human-centered outlook, so it was easy to jump in.

Also, if you can’t join an official project, there's nothing stopping you from pursuing a project on your own. For example, I discovered a German artist named Julia (@Julias_Inkpot) who’s passionate about Mayan and has drawn thousands of characters for fun over the last few years. This kind of work just takes focus and dedication.

Thanks for reading — if you enjoyed this interview, we’d really appreciate it if you shared or forwarded to a friend!

Let’s co-create the first open-source Yucatec Maya TTS (Text-to-Speech) system — trained locally, ethically, and with community benefit at its core.

A project rooted in tech-for-good, cultural restoration, and practical impact.

This isn’t just a gesture. It’s an invitation to act in a way that aligns with the land we’re inhabiting. A project where blockchain devs, sound designers, AI researchers, linguists, and Mayan elders collaborate for real.

https://mxtm.substack.com/p/maaya-taan-30-let-the-language-of