⚡️ What Can A Body Do? ft. Sara Hendren

THURSDAY: Let's talk technologies of abundance, accessibility, and care

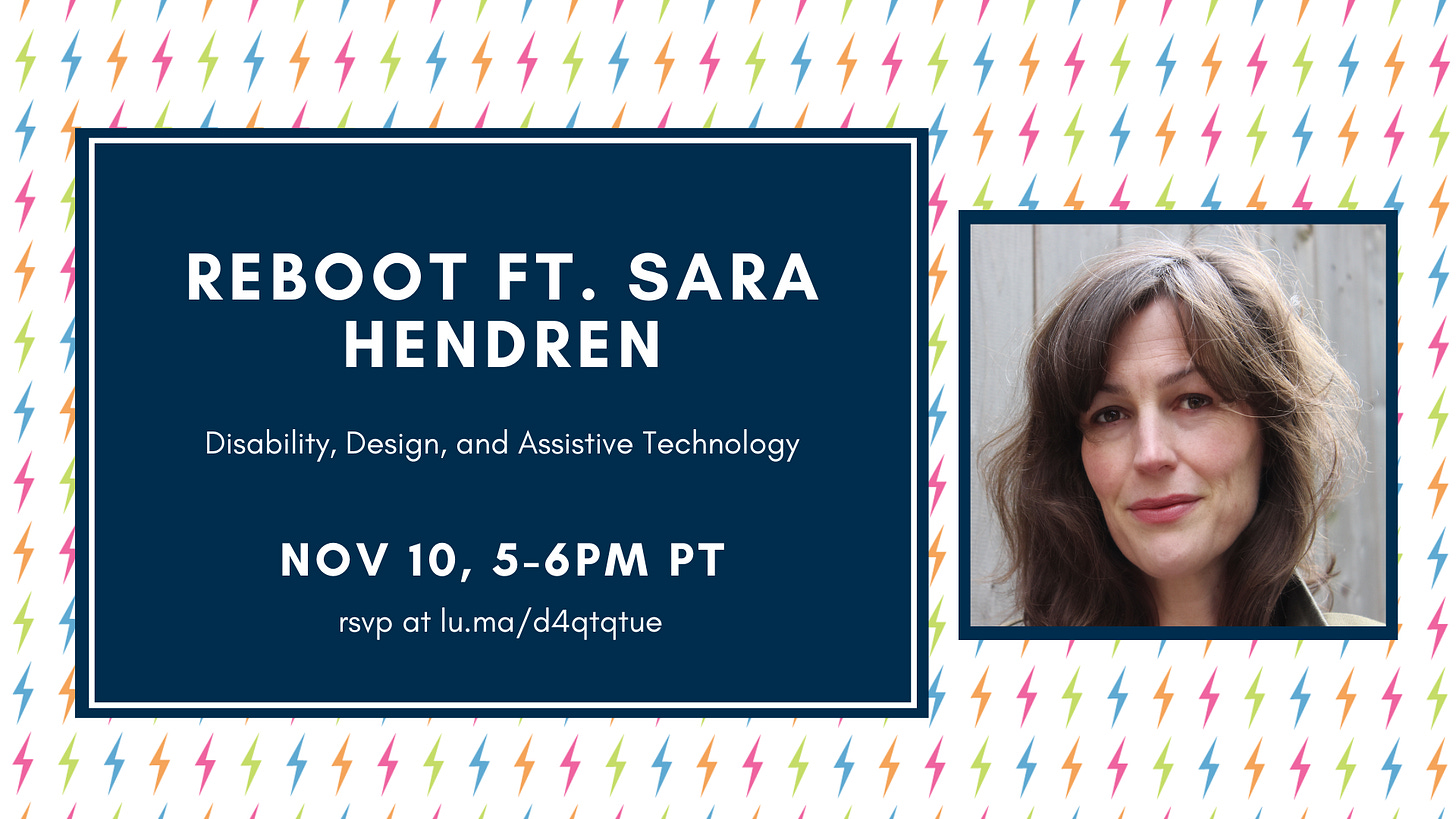

Our guest for this Thursday, November 10 is Sara Hendren, an artist, design researcher, writer, and professor at Olin College of Engineering.

Her book What Can A Body Do? prompts us to reimagine the design of our built world through the lens of disability and accessibility, exploring ideas from cyborg arms to customizable cardboard chairs to deaf architecture. I’m especially excited because she frames the discussion not around constraints, but rather abundance and imagination.

RSVP at this link, or keep reading for our review of the book:

📖 what can a body do? by sara hendren

by Pearl Zhang // edited by Shira Abramovich

As a person with a vision impairment, I cannot remember a time in my education without assistive technologies. From Chrome extensions which changed font colors from black to teal and magenta to advanced head mounted eyewear displays, I felt the one constant in my K-12 educational experience was the presence of complex and hard to navigate technology. Although these technologies were helpful in making modules and educational sites more accessible, they also reminded me that I did not fit the profile of a typical user. These technologies were aimed towards returning me to what able bodied people viewed as normal, rather than meeting me at where I was in the present moment and honoring the richness of my full embodied self.

In her book What Can A Body Do?, Sara Hendren, a design researcher and professor at Olin College of Engineering, depicts the adaptation of bodies to the built world and the ways in which the design of technology and everyday objects can honor the innate dignity that every person is due. Drawing on the fields of disability studies, human computer interaction, human centered design, and science and technology studies, Hendren powerfully brings to life the lived realities that disabled people encounter as their bodies clash with the built world, and how they creatively engineer their environments to reclaim their space and assert their agency.

Hendren separates stories by overarching themes: each chapter has a title such as “limb,” “clock,” or “time,” providing a cohesive structure to orient individual narratives that form the foundation for Hendren’s analysis. The stories depict a broad range of experiences; disability does not discriminate. From a father named Chris using his prosthetic arm to peel and pit avocados and untwist the lid from a jar of peanut butter, to the re-design of Starbucks at the Gallaudet School for the Deaf being based on key principles of Deaf architecture, to a supportive chair made from hundreds of layers of cardboard sheets, to the design of Dutch assisted-living centers for the elderly with dementia — Hendren writes with the keen eye of an artist to capture the universality of the lived experience.

An example of how design reveals points of connectivity in human experiences is the previously mentioned Dutch care facility Hogeweyk (pronounced like hog-awake). A nursing home for Alzeheimer’s patients, it also contains restaurants, storefronts, gyms, and theaters — a planned mini-community. By imaginatively interpreting favorable surroundings, it ultimately creates an environment where people’s inherent humanity and dignity, in spite of their current condition, are encouraged to flourish and where their needs are honored. The semi-fluid nature of Hogeweyk enables the public from the town Weesp in the Netherlands to enter restaurants and sit down to have a meal there too. The blurring of private and public creates a community where people, in spite of their bodily differences, sit down and break bread. Above all, the genesis of Hogeweyk models a formative shift of thinking: a shift from individualism to dependence. Hendren writes, “Dependence creates relationships of necessary care – care that may be undertaken by individuals, families, local communities and municipal organizations, churches and mosques and temples, states or nations, or all of those in some mix,” highlighting the community forged around people’s shared contexts and connections and how these communities slowly but steadily build interdependence.

Interdependence features prominently in each story. One of the stories I found most touching was the story of Niko, a two year old boy diagnosed with a rare genetic mutation that causes developmental and motor delays. To provide optimal physical support for Niko, his parents collaborated with his physical therapist and a designer at the Adaptive Design Association to create a chair crafted entirely out of cardboard sheets ingeniously stacked on top of each other specifically for his condition. In part due to my own experience navigating disability, I loved seeing how the people in Niko’s life embark on a journey with him and share in the joys and pains of life — together. Each person touches another, and another, culminating in ripple effects that magnify communities, reminding us that we are not alone.

Hendren’s generous storytelling is complemented with insights into disability history, providing glimpses into the work of disability activists and philosophers. As a budding technologist, I found the emphasis on disability history and philosophy especially resonant. As technologists, we have our own biases and assumptions with which we program and design software that result in technology for the typical user. However, by paying attention to the long history of disability studies, software engineers and designers receive an invitation to answer “what can a body do?”. We can create technologies of abundance dedicated to meeting people in their current moments. We can dream up better solutions and co-design in solidarity with marginalized communities to build anti-ableist interventions that reduce harms in the status-quo.

While reading, I wished to see more on how the cultural perception of disability influences the technology design. At the same time, addressing these issues would have detracted from the book’s thesis: once we acknowledge that all technology is assistive and all bodies are different, we appreciate expressions of beauty throughout all aspects of life and that we all deserve things and spaces to express our authentic selves.

I found What Can A Body Do? to be deeply moving and teared up at multiple sections in this book. Yet, questions lingered. What would it look like if person-centered ethos of compassion were embedded into design choices for institutions and technological instruments from the very beginning? How can we design technologies to accommodate the access intimacies of our friends and neighbors, and reforge and repair the ways how people are excluded by the tools already constructed? What do we owe to each other? Hendren’s prose emanates generosity and openness, a consistent reminder to re-imagine our lived realities into a metamorphosis of what can be and is possible.

Pearl Zhang is a senior at Swarthmore College studying computer science and education. In her free time she enjoys reading fiction and memoirs and exploring hole in the wall restaurants.

🌀 microdoses

For related reading, check out Reboot’s mini-reviews of Design Justice or editor Shira Abramovich’s personal essay Beyond + Escape, a reflection on (in)accessibility in CS culture for Kernel Magazine Issue One.

Tech Workers Coalition published a “Layoff Guide for Twitter Workers,” which covers topics from workplace surveillance to local labor laws (and is applicable for any worker facing this economic climate).

💝 closing note

ICYMI: Reboot Student Fellowship apps are open for 2023! Please forward to an undergrad in your life—we promise this isn’t your average tech fellowship.

Also, I accidentally emailed out Jessica’s “Meet the Team Q&A” last night instead of just posting it online... sorry but also give it a read I guess? 🫶

In the ashes of the bird app,

Jasmine & Reboot team