He Jiankui—the Chinese-born, Rice University-trained “mad scientist” who created two genetically edited babies, Lulu and Nana, in 2018—has been disgraced in his home country. He lost his professor job, went to jail for three years in China, and was denied a work visa by the Hong Kong government after release. But on X (formerly Twitter), Dr. He has reinvented himself as a figure of fascination for a certain anxious, transgressive corner of the American public.

—Tianyu Fang

Genes for Memes

By Afra Wang

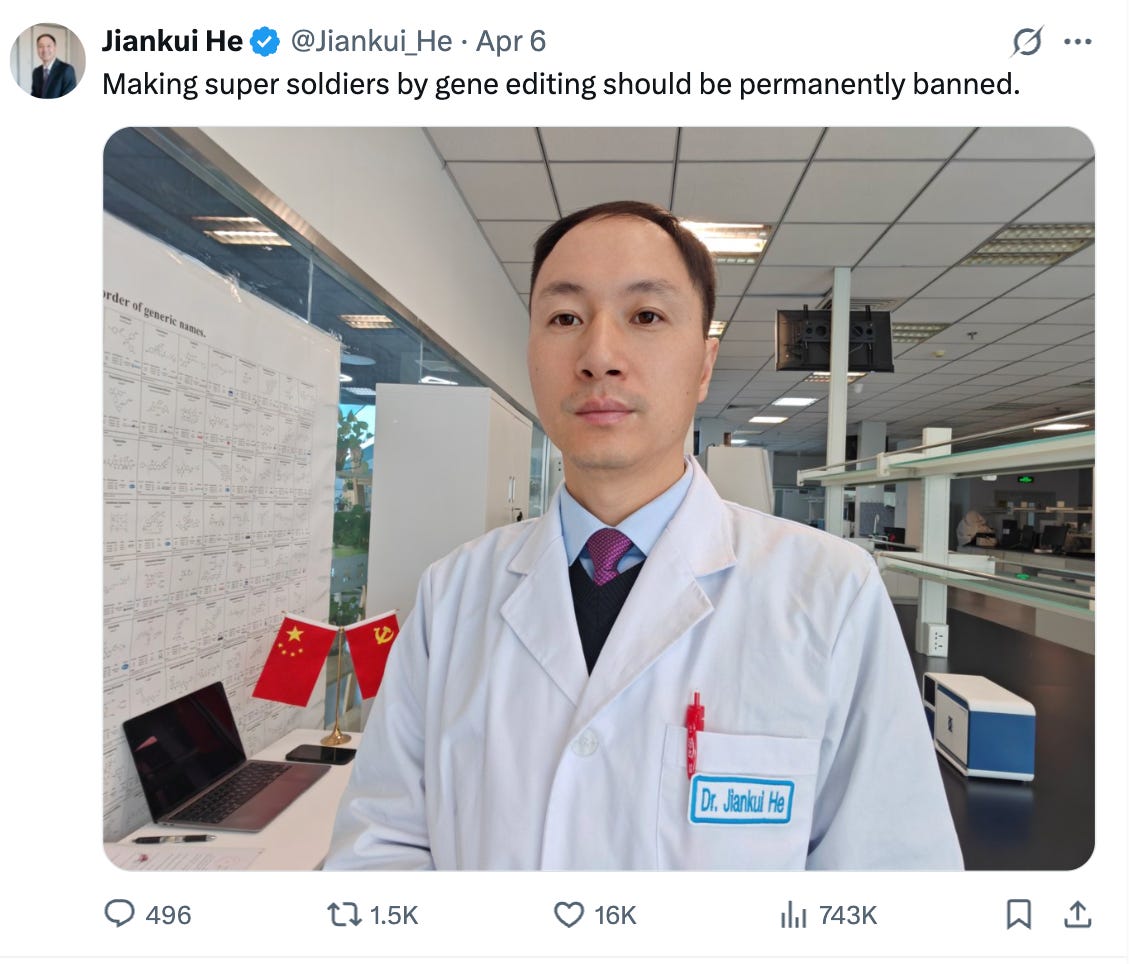

In a spartan laboratory, a solitary figure in a white lab coat stands against the backdrop of China’s national flag and the Communist Party’s hammer-and-sickle banner. The scene is meticulously composed: the central figure stands expressionless before clean lab surfaces and high-tech equipment, without another human in sight.

The man is He Jiankui, a Chinese biophysicist who became synonymous with scientific transgression when he announced in 2018 that he had created the world’s first genetically edited babies using the CRISPR method. His revelation sent shockwaves through the global scientific community for crossing an ethical line many considered inviolable. Rather than publishing in peer-reviewed journals or presenting at academic conferences, He bypassed traditional scientific gatekeepers entirely, releasing YouTube videos days before appearing at a genetics conference in Hong Kong to defend his work to a room full of horrified colleagues.

The backlash was universal. Scientists worldwide condemned his actions for violating ethical standards, lacking proper oversight, and exposing the newborn to unknown future health risks. Within a year, the Chinese government sentenced him to three years in prison for illegal medical practice. The 2018 case became a watershed moment in debates about the responsible use of gene editing technology in humans.

Six years after his controversial experiment landed him in prison—and, arguably, oblivion—back home, He Jiankui returned in late 2022 as an internet persona perfectly calibrated to our cultural anxieties. His English-language X feed is an orchestrated series of provocative contradictions. One day, the “No. 1 scientist in China” might be launching his own memecoin to fund his research; the next he’s posting from an exhibition on the history of the Chinese Communist Party. More recently, he’s accused Chinese President Xi Jinping of confiscating his passport to prevent his wife from joining him in Beijing while announcing his plans to renew his expired U.S. green card—posts that might transform personal grievance into a geopolitical spectacle. In this surreal social media performance, his other posts, like “Making super soldiers by gene editing should be permanently banned,” read as some of the more restrained commentaries by comparison.

He Jiankui has become a kind of specter, slotted into Silicon Valley’s imagination of the mad-scientist narrative: a character who embodies not just scientific transgression and Western anxieties about Chinese innovation, but also attempts to perform the role of political dissident, a scientist martyred by an authoritarian regime. This absurdity and confusion of Dr. He’s feed tells us less about the man himself and more about Silicon Valley’s contradictory relationship with boundary-pushing, especially when that boundary-pushing emerges from China, America’s primary technological competitor.

Transgression in the era of e/acc

Silicon Valley’s rightward drift, and the rise of ideological movements like effective accelerationism (e/acc), have created a welcoming environment for scientific norm-breakers. E/acc has emerged as both an intellectual framework and aesthetic sensibility for Silicon Valley’s neoreactionary, technolibertarian, post-democratic elite. To some of the Valley’s high-profile venture capitalists and founders, democratic processes are an inconvenient bottleneck to innovation. If anti-conformism is a virtue, technologies once deemed unacceptable are gradually becoming accepted by default.

He Jiankui’s X following reads like a who’s who of Silicon Valley’s contrarian wing: Beff Jezos (a pseudonymous e/acc influencer), Aella (the controversial social experimenter and sex worker), Crémieux (the pseudonymous eugenicist), Whole Mars Catalog (an Elon Musk fan account), numerous Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) partners and employees, several biotech venture capitalists, and a substantial portion of the crypto community. Indeed, the Beijing-based scientist is more adjacent to the Valley than one might imagine—his new bride, Cathy Tie, is a Canadian biotech entrepreneur and a 2015 Thiel Fellow. While his reach remains niche, his posts generate the kind of compulsive shareability that tech’s attention economy rewards. Most followers treat him as a “chaotic genius” meme rather than a serious scientist, but that ironic distance only amplifies his cultural function as Silicon Valley’s vibe object.

In a world where vice signaling has replaced virtue signaling, He Jiankui updates the mad-scientist trope. His carefully curated online presence maintains the aesthetic of isolation—empty lab, lone researcher, and obviously staged scenes—while broadcasting to a global audience. His tweets were engineered to maximize attention regardless of their valence. The point isn’t to be right or wrong, ethical or unethical. It’s to be discussed, shared, debated, and memed.

Consider his X declaration that gene editing for “super soldiers” should be banned. On the surface, it’s a responsible statement from a scientist advocating ethical boundaries. Yet it simultaneously plants the idea that such a thing is possible and that Dr. He possesses knowledge of how it might be done. It’s transgression by implication—a rhetorical maneuver that allows him to present as ethical while still capitalizing on the frisson of forbidden knowledge.

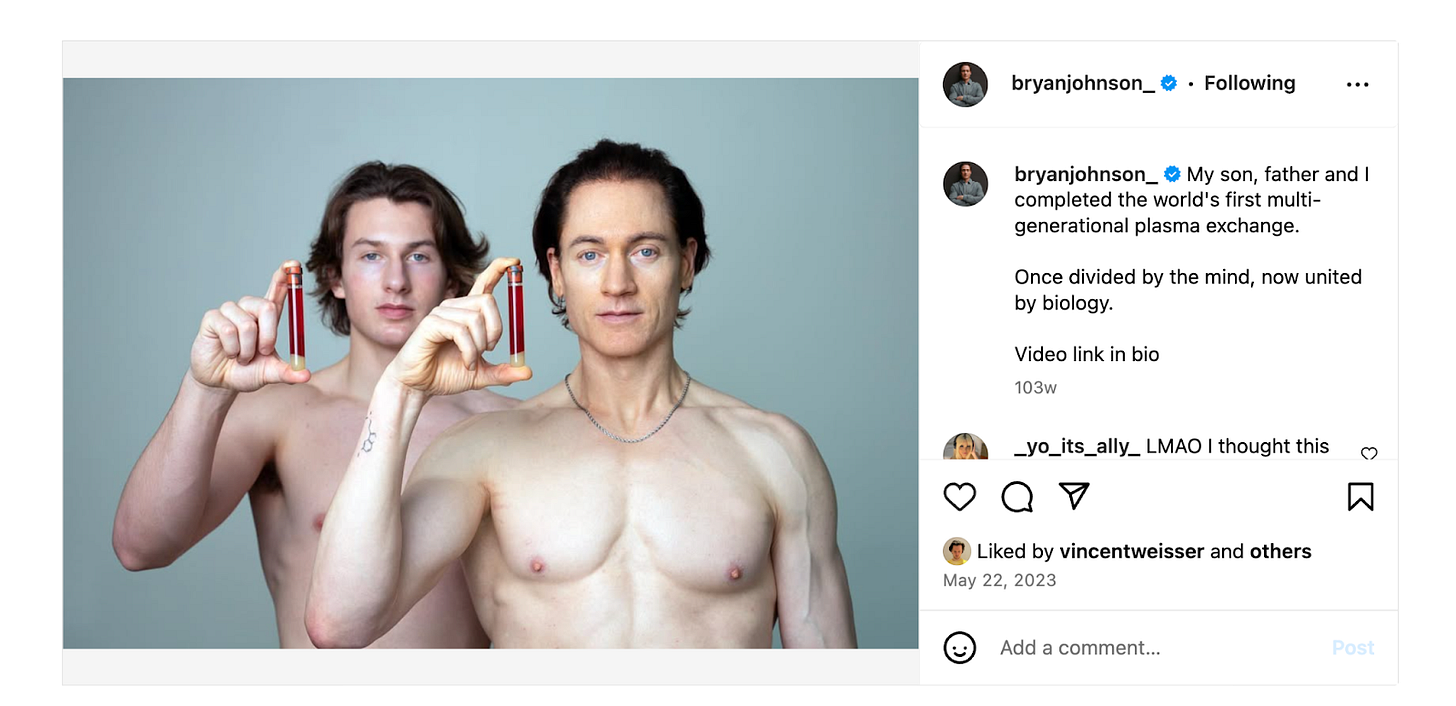

His trajectory reminds me of another transgressive biohacker: Bryan Johnson, founder of Blueprint. Johnson styles himself as a highly modified, almost vampiric figure who’s cheated death through extreme interventions. His social media presence features clinical imagery, descriptions of protocols like blood-plasma exchanges with his son, and a deliberate aesthetic of the unnatural. In one of the Blueprint sales pages, he describes his “7pm Bryan” as “a monster, overpowering, and indifferent about all other Bryans [sic] needs,” framing his relationship with his impulses in almost gothic terms. This performance of the monstrous is exactly what helps market his products and philosophy. Johnson’s transgressive performance has become a successful business model, fueling a lucrative longevity industry that caters to the Valley.

In both Johnson’s promotion of expensive optimization protocols and He Jiankui’s vows to pursue forbidden knowledge, one shared belief is clear: Biology and biohacking can go much further. This sentiment has found an increasingly receptive audience within e/acc movements, which explicitly argue that traditional ethical constraints are holding back human progress. Meanwhile, Silicon Valley’s recent biohacking obsession and revived longevity movements have made more people willing to toe ethical lines and imagine radically different futures: Johnson’s world, where “death is a technical problem,” or He Jiankui’s vision of routine gene editing in everyday life.

In this worldview, both Johnson’s expensive self-modification and He’s genetic interventions represent glimpses of a future where biological limitations become optional. The question is just who gets to control that transition. Where Johnson pushes cultural boundaries, He Jiankui operates beyond these constraints while adopting a voice that suggests the mundanity of that transgression.

The enemy’s mad scientist

Undergirding the biohacking community’s fascination with He Jiankui, too, are new geopolitical anxieties. The wounds of COVID-19 still linger in collective memory—though never explicitly stated, He Jiankui deliberately toys with the “Chinese biolab” imagery that triggers deep-seated fears about Chinese scientific ambitions. When figures like Peter Thiel publicly imply COVID-19 was a Chinese-manufactured bioweapon, and substantial portions of the American public believe similar theories, He Jiankui’s laboratory photos against Communist Party flags become loaded with geopolitical subtext.

The pandemic injected terms like “gain of function” and “lab leak” into everyday conversation, creating a world where any discussion of Chinese biotechnology gets filtered through questions of global biosecurity. As scholar Andrew B. Liu argued in his analysis of the lab-leak discourse, we are witnessing the emergence of what he calls the “Asiatic” racial form, distinct from traditional Orientalism’s portrayal of the East as backward and stagnant. This newer framework imagines China as hypermodern and threatening precisely because of its technological efficiency. Unlike the “Oriental” who was excluded from capitalist progress, the “Asiatic” represents its full and terrifying realization of capitalist progress and its dark excesses.

China’s approach to technology—with its extreme competition, relentless efficiency, and state alignment—presented an uncomfortable mirror. The idealism that once defined Silicon Valley (and often aligned with progressive social movements) suddenly felt like a competitive disadvantage. Lab-leak theories function less as scientific hypotheses than as cultural processing mechanisms, helping the West to make sense of China’s capacity to break the same rules more effectively.

He Jiankui’s work, totally unrelated to virology, still gets caught in this net. As Liu noted, the lab-leak theory “rings true for many, tapping into recurring suspicions that the China of today, behind its inscrutable armies of cheap labor and lab coat–wearing scientists, is up to something fishy.” He Jiankui’s memefied persona seems to deliberately toy with those theories, never explicitly endorsing them but leaving just enough breadcrumbs to feed existing anxieties about Chinese biological research.

His X post from March 2025 declaring “Human [sic] will no longer be controlled by Darwin’s evolution” went viral precisely because it crystallized the West’s fascination and fear: a Chinese scientist seemingly unbound by Western ethical constraints, ready to push humanity into its next evolution. The 18,000 likes and countless meme variations were both entertainment and processing cultural anxiety through memes. He has become the perfect vessel for tech’s contradictory impulses: celebrating bold innovation while fearing Chinese technological advancement. He embodies both what Silicon Valley admires (rule-breaking transgression) and what it fears (geopolitical competition threatening American supremacy).

The Gattaca reality

He Jiankui’s experiments inevitably call to mind the 1997 film Gattaca, which portrayed a future split between the genetically enhanced and the naturally conceived. The film’s exploration of genetic determinism raised questions that still haunt us: Who gets access to genetic enhancement? Who decides which traits are desirable? How do genetic modifications interact with existing inequalities?

These questions feel increasingly urgent as eugenics makes a fashionable comeback. Elon Musk fathers some children through in vitro fertilization (IVF) to select traits. Trump deploys eugenic language about some immigrants having “bad genes” and “poisoning the blood of our country.” On rationalist forums like LessWrong, posts on “how to make superbabies” draw a packed comment section. Companies like Orchid Bio offer embryo selection services to wealthy Silicon Valley families, marketing genetic optimization as just another premium lifestyle choice.

What’s particularly striking in America’s current political reality is how gene editing would interact with its already stratified healthcare system. The convergence of Trump-era deregulation and weakened public healthcare creates perfect conditions for genetic technologies to exacerbate existing inequalities. We’ve seen this pattern repeatedly: from insulin pricing to cancer treatments, American healthcare innovation follows predictable diffusion: first available to the ultrawealthy, then to the well insured, eventually to the middle class through expensive insurance, and often never reaching those most marginalized.

These questions hover around He Jiankui’s current projects, but he sidesteps them with elegant simplicity. His focus on Alzheimer’s, which he claims motivates him because his mother suffers from the condition, presents gene editing as a straightforward medical intervention rather than a technology with profound social implications. The leap from preventing genetic disorders to enhancing capabilities is smaller than we would like to admit, but Dr. He’s narrative skips right over this uneasy territory.

When Dr. He declared in an interview with MIT Technology Review that by 2074—a year oddly precise—gene editing will be as common as IVF and will eliminate all genetic diseases, he was offering a techno-optimist’s dream that conveniently ignores the decades of unequal access that would precede such a future. IVF itself remains financially inaccessible to many, with state-mandated insurance coverage in fewer than half of U.S. states.

In Trump’s America, where healthcare access remains a partisan battleground, the prospect of gene editing technology adds an uncomfortable wrinkle. If gene editing becomes reality, will it follow the pattern of other medical innovations—initially available only to the wealthy before slowly filtering down the economic ladder, but never quite reaching everyone? He doesn’t seem interested in these questions. His vision leaps straight to the endpoint, bypassing the messy middle where most of us would actually live.

He Jiankui stands as a complex cultural symbol: a figure whose significance extends far beyond his scientific contributions. His carefully curated online presence, with its strategic ambiguities and provocations, offers different things to different audiences: a villain for bioethicists, a hero for technolibertarians, a cautionary tale for regulators, or a symbol of China’s unfettered scientific ambition for geopolitical analysts.

What makes He Jiankui compelling isn’t exactly his science but how perfectly he embodies the tensions of our moment: between scientific advancement and ethical boundaries, between national pride and global responsibility, between institutional authority and individual agency. He has transformed himself from a disgraced researcher to a cultural signifier—someone whose very name evokes debates about the boundaries of human intervention in our biology.

As Dr. He continues his digital performance of the reformed renegade scientist, seeking legitimacy while still trading on his transgressive past. In that carefully staged laboratory image—standing alone against the backdrop of the Chinese flag, tweeting about biotechnology’s frontiers—we see Silicon Valley’s contradictory impulses: celebrating rule-breaking innovation while simultaneously fearing China’s technological rise.

He Jiankui has become the perfect specter for our time—a figure who allows tech culture to process its own anxieties about innovation, competition, and ethical boundaries through a convenient foreign other. His carefully crafted persona, with all its contradictions and ambiguities, shows how the scientist has evolved from an isolated genius to a networked performer, and how our collective imagination about scientific boundaries is shaped as much by memes and social media as by academic discourse.

Afra Wang is a host of the Chinese podcast CyberPink and writes the newsletter Concurrent.

Reboot meets our readers at the intersection of technology, politics, and power every week. If you want to keep up with the community, subscribe below ⚡️

🌀 microdoses

It’s been half a year since many U.S.-based TikTok users flocked to Xiaohongshu. Meghan Boilard on her experience of trying to make sense of the app as an American.

Julia Steinberg on Cluely, and why college graduates find elite jobs useless.

Jacob Dreyer on America becoming more like China, and Damien Ma and Lizzi C. Lee on why that can be a good thing, if done right.

And lastly, Joshua Citarella interviews Francis Fukuyama.

💝 closing note

Thanks for reading. Have ideas or a pitch? Send me a note—tianyu at joinreboot.org.

Our print magazine, Kernel 5, is out; get your copy here!

—Tian

Married then had a lab in Texas. Guess he’s ready to hack his own baby?

He's work was worse than a crime, it was a mistake! The CRISPR baby thing was mostly notable for how scientifically and medically pointless it was. The baby's mom wasn't HIV positive so little to no risk of transmission so the CCR5 knockout was pointless, and he didn't even achieve homozygous CCR5 knockout for one of the embryos. And it wasn't like anyone doubted it could be done, people already made CRISPR-edited mouse embryos routinely, it's just that it was stupid to do. Had he picked a sensible edit like, I don't know, a mutant transthyretin gene knockout then there would at least be an interesting conversation.

Meanwhile while I'm not sure the above is broadly understood, it's nevertheless true that he's broadly considered a big joke on the Internet not some sign of anything sinister.