The arrival of autonomous vehicles (AVs) in San Francisco has been momentous to say the least—a series of staged rollouts, rollbacks, and fistfights with the new machines as people attempt to renegotiate the norms of the road.

There is some promise to the new machines, but as with any new technology, it should be deployed responsibly to meet a real need. Given that AVs reinforce a particular arrangement of the urban environment, I believe this is a challenge that requires the full participation of the public.

Freewheeling Futures

Under a waning crescent in the crisp September night, a masked vigilante took a hammer to a robotic Chevy Bolt.

This bizarre scene seems more at home in a comic strip, but it’s just another night in San Francisco in 2023. Fully driverless cars, primarily operated by Cruise (owned by General Motors) and Waymo (owned by Google), have become a common spectacle on the streets this year, drawing lingering gazes from tourists and long-time residents alike. The California Public Utilities Commission recently gave the green light for these companies to offer rides to anyone, at any time, for a fee. What was once an “unimaginable future” reserved to the pages of sci-fi novels is now roaming the roads.

The Bay Area is a region whose last century has been shaped in many ways by the technology industry, whether ushering in the iPhone or pushing housing prices through the roof. But the arrival of autonomous vehicles feels notably different—perhaps because the future is no longer in the palm of our hands, but approaching us at 35 miles-per-hour in a 2-ton metal shell. Resistance to the robocar has come in forms other than blunt force as well; local politicians have taken to the press to call these launches an unsavory “public experiment,” and Safe Street Rebel (a local pro-pedestrian organizing faction) began temporarily disabling vehicles by placing traffic cones on their hoods. “Throwing rocks at the Google bus” has a brand new meaning.

Having worked as both a community organizer and a product manager (and now as a student-researcher at the Goldman School of Public Policy), I am ultimately optimistic about the potential of new technologies to sustain the prosperity of people, place, and planet. In my eyes, we shouldn’t dismiss the arrival of autonomous vehicles outright, but also can’t accept whatever shows up on the streets with blinders to their negative effects. Contrary to the usual logic of Silicon Valley, true progress isn’t a vehicle driving in whichever direction the next multinational investor points in; we, the residents of the city, should have the ultimate say in shaping the future to meet our needs and make our streets as livable as they can possibly be.

Automotive Obsessions

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) aren’t the first groundbreaking technology to shape our cities—in fact, finding new ways to quickly traverse great distances has been one of the defining problems of modern urbanism. As cities became significantly larger and more complex alongside industrialization, the challenge became how to efficiently move people and things from one end of a city to another, or plan cities in such a way that minimized travel time and cost. The car was far from the only solution; buggies, streetcars, bikes, subways, railways, and other innovations in mass transit shaped this period. But in the early 20th century, Henry Ford's innovative mass production techniques made the automobile more affordable for the masses, and the car quickly became the preferred solution for getting around following declining investment in public solutions.

As we are deeply familiar within today’s world, the unregulated proliferation of consumer technology isn’t always guaranteed to result in the optimal social arrangement. As city planning codes bent under the pressure of the invisible hand, roads became wider and parking lots spilled blank concrete slabs across the land, sacrificing land that could have been housing or pro-social spaces. Car-centric urbanism is also historically synonymous with white flight; as highways shuttled white workers into suburbs surrounding the city’s core, Black neighborhoods across the nation were bulldozed to make room for soaring freeways (a process now known as “urban renewal”). Today, San Francisco’s weekdays are defined by the near daily commute of hundreds of thousands of cars on the Bay Bridge, contributing to congestion, social isolation, carbon dioxide emissions, and numerous other issues of health and safety. Much like the “social dilemma” of unchecked social media that we technologists now refer to, the unchecked adoption of cars (and the weakness of urban planners to balance their influence) has led to an urban dilemma of lasting and seemingly inexorable impacts. Our over-reliance on cars—not who or what is behind the wheel—is likely our most pressing problem.

Those of us who still dream of more livable, equitable cities will always call back to the transit futures we left behind: the trains, buses, and bikes that have been largely forgotten in modern American cities. Other cities across the world have continued to push the limits of mass transit technologies; most of Tokyo Metro’s trains run autonomously and support over 7 million riders daily. Medellín supplemented its train system with cable cars and escalators to help its residents traverse steep terrain. Copenhagen, a city which was largely designed around cars up until the 1970s, made significant investments in safe bike and pedestrian infrastructure, such that nearly 50% of its commuters use bikes. These investments in transportation infrastructure reflect the pro-social priorities of both the public and private realm in these countries, and show that such a shift is still possible for us in America.

But without the proper checks and balances, the confluence of capital from General Motors, Google, and the broader venture capital industry will likely be able to push their particular future of transportation into reality without considering their deleterious effects. We saw this play out in cities across the world through the story of ridesharing companies, whose domination is often justified by consumer demand and shareholder obligations despite the poor records on congestion and labor; while autonomous vehicles avoid the labor issue, it’s not clear how a future with more autonomous vehicles will actually improve congestion. With an increased presence in Sacramento and early usage, it seems that AV companies are destined to take a similar path at ridesharing, reinforcing a car-centric future for American cities rather than one oriented around mass transit and human-powered movement.

…that is, unless we meaningfully question how we make decisions about these new technologies and their impact on our daily lives.

Putting the Public at the Wheel

Time to pause and think: how do we make decisions about an emerging technology to ensure that it delivers the maximal benefit to society? Car culture was always about prioritizing individual freedoms over our collective needs; if we’re going to welcome a new player on our roads, they’ll have to play by our rules, rather than foisting their rules upon us. Doing so will require innovating not just on the cars, but upgrading how we govern technology in the public sphere.

The advent of generative AI has revealed similar opportunities to guide the development of a powerful technology according to people’s needs and desires. OpenAI in particular opened up a grants program for “democratic inputs to AI,” inspiring a flood of responses from organizations interested in technology policy and governance. However, it’s still unclear how these ideas will be integrated into the design, development, and deployment of future models, or if they will be used at all. On the other hand, government regulators are now playing catch-up, issuing a litany of executive orders and guardrails to ensure that the technology minimizes harm. These, too, often lack specificity about the people affected or the impact to existing domains, and fail to put the people who are most vulnerable to the negative impacts of generative AI at the forefront of the decision-making. All said, there’s clearly much more work to be done, but these attempts should give us hope that democratic control of emerging technologies is possible.

When it comes to autonomous vehicles, I believe we can build on these methods for even more effective, accountable governance. At the most basic level, all residents should have a way to easily report dysfunctional behavior; after all, these vehicles’ behavior on the street affects far more than just the passengers inside. The San Francisco Fire Department has actually taken the lead here by collecting every instance in which an autonomous vehicle has become an obstacle to their operations. For everyday residents, Twitter (or “X”) and Reddit have become the de facto bug reporting platforms, collecting videos of close encounters and confusing lineups of autonomous vehicles adding to traffic. While these methods are reasonably effective stopgaps, there is no promise that a company employee or city staff member will see and respond to messages on unofficial channels; instead, we should have more streamlined channels to send feedback to the responsible entities, and they should have a legal obligation to address these issues. This could be as simple as adding “interactions with autonomous vehicles” as a category when filing a 311 report.

But simply reacting to poor behavior is a one-sided conversation, with AV companies in the driver’s seat. The people who will have to deal with these vehicles everyday should have a say in what the new norms of the road should be, whether we’re talking about how much space to give pedestrians, how autonomous vehicles can communicate with drivers, or how the data that they collect is used. These kinds of recommendations could be well-suited to a creative community discussion; residents could be assembled to form recommendations based on their experience and advice from experts, much like they have been in cities around the world to resolve tricky urban problems via Citizens' Assemblies or within community design labs. Moreover, we’ve already seen how otherwise inscrutable machine learning systems can be directly informed by rules that people set for them; Claude, for example, is based on a “constitutional” system that bakes in explicit declarations for how the algorithm will respond to certain inputs. No matter the exact form, we would need to make this an ongoing conversation with consistent input from the city’s pedestrians, bikers, and drivers—a notable departure from today’s public experiment.

The most powerful methods of citizen engagement would address the harder and more fundamental questions: what is the role that these technologies should play in meeting our city’s transportation needs, and what is the optimal extent of its use? While most planners agree that the vast majority of uses for AVs can be addressed more effectively by prioritizing public transportation and mixed-use urbanism, it’s possible that AVs could enable new levels of independence for individuals with disabilities or the elderly. The key here is proactive planning by government agencies like San Francisco’s Municipal Transit Authority, which can then determine the best ways to support AVs for their most beneficial use cases while simultaneously considering all other forms of safe and sustainable transit. In that process, technology can also play a role in facilitating the public will; Taiwan’s government is particularly notable for using a collective intelligence technology called Pol.is to facilitate discussions about how to regulate Uber.

New Moves

For now, we’re still in the early days. In light of various crashes and stalling instances, the California Public Utilities Commission demanded that Cruise reduce its fleets by half. Operations have continued, but virulent discourse rages on Twitter and other forums as people try to figure out what the new normal should be.

Fog City’s future is conjured by a chorus of voices, and the familiar humming of the robotaxi is but a single tone. No outcome is predestined, and while overwhelming amounts of capital can sometimes make it seem like progress drives in a single direction, there are always alternative visions bubbling just beneath the surface. The collective imagination of this city has already produced plans for a more livable and equitable built environment, whether expanding the Embarcadero into a broad seaside plaza, turning Valencia Street into a pedestrian promenade, or simply improving (and saving) public transit. As such, we need to come together as a community to determine if and how autonomous vehicles meaningfully contribute to these visions. Both the government and private entities have a role in facilitating the public’s will on this matter.

If you live in San Francisco, now is a good time to get more involved in advocating for livable streets. Attend the Municipal Transit Authority’s meetings, or maybe write the Board a letter. Join local organizations that advocate for more people-centered urbanism. And as always, get to know your neighbors and get their opinions on what’s happening in your city.

Instead of a hammer, maybe we can give the masked crusader from that September night a microphone—a voice to determine their future.

Humphrey Obuobi is an editor of Reboot. In addition to his roles at Reboot and UC Berkeley, he runs LETS Studio, a creative studio dedicated to democratic social innovation. His favorite SF Muni bus line is the 33, which he still uses nearly every week despite living in Oakland.

Reboot publishes essays on tech, humanity, and power every week. If you want to keep up with the community, subscribe below ⚡️

🌀 microdoses

Bloomberg published a cool pair of essays side-by-side, laying out cases for and against self-driving cars.

Femi Adeyemi speaks about the importance of place and the magic of internet radio

A culture and information distribution network managed through USBs

Urban Technology at University of Michigan is doing an excellent job of merging the practices of architecture, urban planning, and technology; their Substack is a neat documentation of their insights.

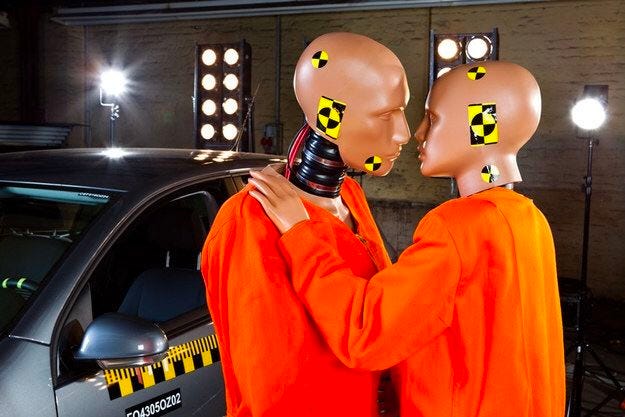

Presented without context (via are.na)

Toward more democratic cities,

Humphrey & Reboot team

Nice piece! If I may add what I think is another under-discussed aspect of AVs; they can be solitary. I stopped driving a long time ago but use ride-sharing occasionally, when I recently took an AV to work one morning, I suddenly realized that it was the first time in years I'd been alone in a moving car. Not even a driver with whom to have (or not have) a conversation. Waymo cars humorously let me pick the music because there's no driver who's tastes might clash with mine.

Public transit seems to me obviously where we shoult invest more: it has these great positive externalities on the environment and more equal access. But there's also that important comaredrie of shared transit spaces, and AVs feel like a worrying step backwards in this regard.