Artificial Means Human-made

Artists Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst on Sentience, Spirituality, and Staying with the Trouble

This week we have an interview with Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, artist-musicians whose AI projects are as invested in developing new protocols for cultural production as they are in technical experimentation. Quincy’s conversation with them comes on the heels of their latest exhibition opening, and reveals how central collectivity is to their practice. If you’re lucky enough to be in Berlin between now and January 18, check out Herndon and Dryhurst’s Starmirror at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art.

—Hannah

Artificial Means Human-made

By Quincy Mackay

An old margarine factory in central Berlin houses the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, which artists Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst have transformed into a chapel. Their new exhibition, Starmirror, invites visitors to reflect on emerging relationships between humans and AI. A dark corridor leads to an antechamber flanked by 3D-printed columns, each ornamented with imagery generated from Herndon and Dryhurst’s PD40M dataset of public domain visuals. At the center rests Ur-Hildegard Training Corpus, a songbook produced by an AI model trained on the music of the twelfth-century mystic Hildegard von Bingen.

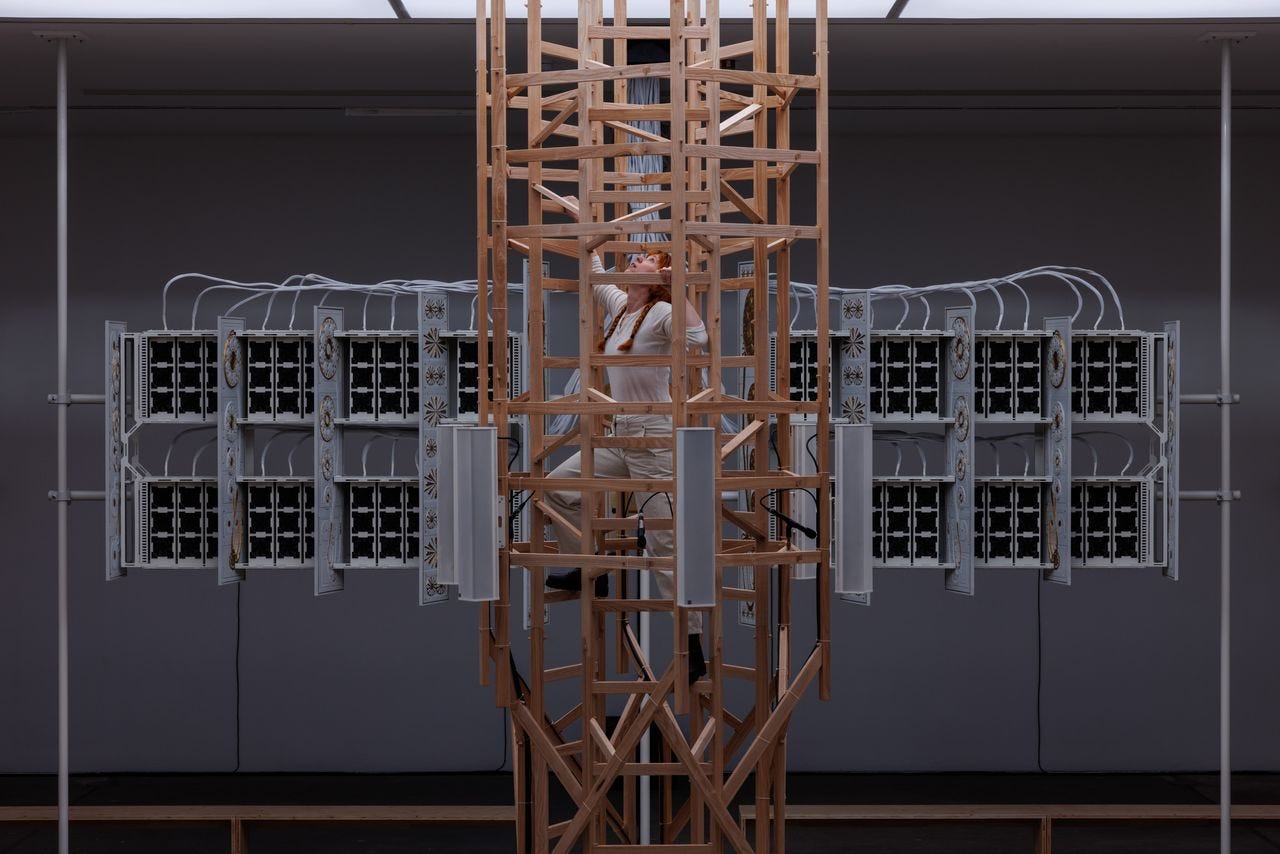

The exhibition continues in KW’s main hall, where a large wooden ladder rises through a lightbox in the ceiling, encircled by rows of benches arranged in a square. Hymns float through the space from overhead speakers. At the back stands The Hearth, an organ built from GPU cooling fans programmed to spin at specific frequencies to produce musical notes. Sitting in the pews, visitors are immersed in layered compositions, some recorded by live choirs, others generated by AI. The compositions are a mix of von Bingen originals, other medieval chants, and outputs from the Ur-Hildegard model, leaving us unsure whether what we hear is human, machine, or divine.

Herndon and Dryhurst collaborated widely to realize the exhibition. The spatial design was developed with the architecture studio sub, and the ladder structure was built using a complex CNC joinery system developed by the fabricators at STEEV. The light box was created by light designer Bianca Peruzzi. Visitors can also contribute their own voice to a public choral dataset during guided group-singing sessions.

Herndon and Dryhurst have always been more interested in input than output. Between releasing an album featuring an AI model in 2019 and developing a tool that allows anyone to transpose any song into Herndon’s voice, they have embraced AI experimentation even as much of the art world resists its encroachment. The duo pair these technical experiments with new organizational models, including collective ownership protocols and data trusts.

We met for a sprawling conversation a week after the exhibition opening to discuss the surprising role spirituality plays in understanding this technological frontier. Our interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Quincy Mackay: You’ve been working with AI for a long time. Your album PROTO, which featured a custom AI model, came out in 2019. What is it like having your niche explode into the Next Big Thing?

Holly Herndon: PROTO was released in 2019, but, of course, it took us two years to make it, so we were working on it from 2017. It does feel like a lifetime ago. Plus COVID happened mid-tour, and then we had a baby. I was in this postpartum cocoon, a very cloudy, loving space where you’re not really engaging with the outside world so much—and that’s when the AI conversation exploded. That was so weird, because I came out of my cocoon and then all of a sudden everyone had these crazy opinions on this thing that we had been dealing with as specialists. But then all of a sudden it turned into what felt like a culture war, where you choose a team, you’re either for or against. That was so alienating to experience directly after coming out of the cocoon.

MD: It’s validating that people are discussing it, but Holly and I are regularly frustrated by the coarseness of how something quite complicated is approached, but that’s just what happens when the floodgates open and everyone jumps on. At this point we’re pretty battle hardened and good at sticking to our guns. We’re just trying to remove ourselves a little bit from the tumult.

QM: Your work situates AI within a bigger historical context, which is something Starmirror does as well. Where do you place AI in this longer arc of technological development?

HH: Artificial means human-made. We like to think about AI as a continuum of various collectively created human accomplishments over the span of human intelligence. So rather than thinking about AI as some kind of alien other, we see it as something that still comes from us. I find something really comforting in that.

We’ve seen similar processes of new technologies shaping culture in music since the dawn of early notation protocols. Neumes was a technology that changed how people were writing an old Roman chant. Then we see the development of modern notation, then we see the printing press, and the creation of the church organ, all of which changed musical rituals and writing as well as our relationship to music. You can go even further. We have recorded music, then we have the synthesizer. With each one, people have asked deep philosophical questions about what is human? What is machine? What is automated? What is our creative intellectual position in that loop? And I think it’s good to keep questioning those things and to keep trying to understand where we fit into this. But the struggle or the questioning is not necessarily new. It happens with each new step in a technological process.

QM: I like that you decided to go all the way back to the 12th century with your main artistic inspiration for this exhibition, Hildegard von Bingen, and the religious angle you brought, creating a church-like space in KW. Maybe you can talk a bit about how you think about spirituality, myth, and faith, and what connection that has with AI?

MD: One of the reasons we found Hildegard von Bingen quite interesting is that, in a sense, she was receiving prompts from an unknown origin. She was a visionary, literally. She hallucinated [luminous imagery of blinding light and cosmic spheres]. It’s interesting amidst the kind of moral panic around models right now. I think there’s a tendency in the general discourse to panic or over-embellish certain concerns about things to such an extent that you lose grounding of your own principles. One example is an overemphasis on machine learning models producing truth. All of a sudden, progressive corners of society have gone from questioning the idea that there could be one fundamental truth to insisting that LLMs need to be regulated to produce the absolute truth. It’s similar to how, 10 years ago, it would have been controversial to defend copyright in progressive circles. Now that has completely flipped such that allegedly we should all be supporting Getty images. I mean, it’s just absurd, right?

There’s some legitimacy when it comes to hallucination or AI psychosis, but generally speaking, there’s a kind of conservatism that comes along with the moral panic. The history of scientific innovation, artistic exploration, and religious divination is all about opening your mind and losing it a little bit. I think that when we’re in the domain of art, or imagining where this goes, I’m really cautious to dismiss the idea that one shouldn’t lose one’s mind a little bit. I have a quasi-spiritual commitment to that, where I enjoy finding strange coincidences in the world or trying to divine signals from things. I think that is common across most faiths, and in general I’m very open to it.

HH: From a musical standpoint, we’re both really attracted to vocal music that’s inspired by a kind of passion, and the ecstasy of religion or the ecstasy of a greater power can be this beautiful driver for a specific kind of passion and vocal musical delivery, and you see this across cultures.

Another thing we’re really interested in is the idea of the archive. For Starmirror we’re trying to build this public domain data set. When we’re looking at this shared human data that we’re building all these models on, we see so many flaws in the history of our archive. It’s a really big question in music because we’ve only had recorded music for a few decades. Of course, none of Hildegard’s original music was recorded; we just have these scores. They’re not even in modern notation—we have Neumes, which is this really cool, weird form of notation which the performer interprets with their own specific ornamentation.

Then along comes Pope Gregory and he tries to unify the chant—that’s where we get the Gregorian chant. You could almost call it a whitewashing or a simplification of how that music was delivered. In reality, it was probably way more microtonal, almost Arabic sounding, with different scales and ornamentation. These different political projects can actually impact how we see our history and our archive. And I think that’s one thing that’s made us really obsessed with capturing things, because the archive’s always going to be imperfect.

MD: Feeling like you’re part of something that’s greater than the sum of its parts is obviously a very religious impulse and seems to be, at least through our interpretation, the beauty of these models. There are these emergent properties, these models that rely on all of us as a group, but no one in particular. And you could make a kitsch interpretation that says we’re worshiping AI, but that’s not it. It’s more about feeling like you are part of something that is bigger than yourself, and the sense of submission to that greater whole is a thing of beauty. It’s at odds with a peculiar renewed emphasis on individualism that wants to say “this is my picture and my picture’s really special.” We want to say that none of us are special, but in aggregate we are incredibly special.

QM: Would either of you describe yourselves as religious in any way?

HH: I think spiritual is a better word.

QM: Do you think there are things we can’t know? Maybe that’s a better way of putting the question.

MD: Absolutely.

HH: 100%.

QM: Is AI one of those? Can we know how a machine learns?

MD: I don’t think we have the hardware to be able to interpret how an AI thinks, but you can imagine a near-term scenario in which we have models that can interpret what’s going on with our current models and then synthesize those down to a conclusion that is fairly accurate.

It is peculiar for us to have software or tools that can navigate that vastness better than we can. We’ve had microscopes and other tools, but AI navigates billions of data points. Some of these protein folding projects are totally abstract and we have tools that can digest that vastness according to our instruction, and then synthesize it in a way that we can use.

HH: It’s also not 100% new. I remember watching this wonderful German documentary called Master of the Universe. It’s about an investment banker called Rainer Voss and the subprime mortgage crisis. He was basically saying that bankers didn’t stop it because they didn’t understand it. This is coming from someone who was at the very top. We have these super complicated systems that we can’t fully wrap our heads around and we’re already living with them. That’s not always a good thing. As was the case with the subprime mortgage crisis it can spiral out of control and there’s no one driving the car.

It is within our nature and within the nature of these vastly networked systems that things will be more complicated than an individual mind can understand. We have to hack our way through it. We have to find ways to collaborate with these other brains so that we can then understand what’s happening. It’s a very scary, cyberpunk future, but we’re already living in it.

QM: You’ve said that you cope with a fear of the unknown by going in at the deep end and learning as much as possible about that which you fear.

MD: Yeah, stay with the trouble.

QM: How do you hope that visitors to your exhibition might confront their own fears?

MD: The difficulty with a public exhibition like this is that you have to leave a lot open to interpretation. I think that’s a benefit of a public exhibition, and so the hope is that there are different layers. There’s going to be a very small group that wants to nerd out about this stuff, but the hope ultimately is that we can produce something beautiful that doesn’t feel alienating. We’ve tried to avoid leaning into a lot of cliché representations, right? There are no screens. I hope it doesn’t come across like you’re about to be displaced by a ’borg or something like that. We just want a nice contemplative space to listen to this stuff that stays with people. If we were to get too heavy with people, it could be alienating. It used to be fun to alienate people, but we’re not in that phase of life anymore.

QM: Turning to the exhibition space itself, I was really stuck by how social it is. You have this circle of benches and you end up actually looking at people as they take in the experience in different ways. Maybe they’ve got their eyes closed, maybe they’re trying to film it, maybe they’re just chatting. It’s a fascinating way to think about AI because if we stick with the religious metaphor, it’s like a confessional. You sit and you type on a computer, and it’s this very private and individualized experience. What are the collective ways of interacting with AI that you’re trying to make?

MD: If you look at liturgical environments, oftentimes people will face a pulpit or something like that. But we borrowed from the Sacred Harp tradition, partly because that’s where Holly’s from. It’s more of a horizontal arrangement where you sing in a square, so you are always looking at each other. Then different people step up to be the caller in the middle, which is a really interesting experience because you’re giving and receiving at the same time. You give by calling the song, but then you also have the best seat in the house. So when everyone sings back to you, you in the center become the main audience member. It’s really beautiful. That feels more in the spirit of this idea of saying that these models are all of us.

It’s a bigger meta point we’re working on, trying to push back against the idea of an inevitable automated future as one of isolation and being served ever more tailored, personalized media. It’s a reasonable assumption because we’ve had years of media pushing that idea down our throats. That will exist, and it’s already happening, but our argument is that a lot of people’s concerns are more cathartic complaints about the platform economy, and all these hijinks that isolate us. I think it’s the exact opposite. I think the natural interface for machine learning and these models is voice. I don’t see screens as being the natural interface for this stuff.

QM: That’s a good time to come onto this idea of protocols you work with, which are systems to ensure fair use and fair monetization of data and work in the era of AI, arguing that the 20th century models simply aren’t fit for purpose anymore. The KW exhibition has some work on this, and you’ve proposed legal and financial frameworks that would, for example, enable artists to consent to their work being used as training data, and then receive royalties when the model produces other profitable media. Can you go into more detail about the models being proposed here at KW?

MD: We’ve been involved with data politics for a number of years, and accidentally ended up working on that with a lot of different actors. We want to build what Holly would call manners around this stuff. There’s this idea of the public domain that many people under 30 may not even know, because it came with a web 1.0 politic of people saying, “I’m willfully putting stuff out in the world and I want for you to be able to use it freely.”

For this exhibition, all the works are in the public domain. We’re training a model called Public Diffusion, a snippet of which is in the exhibition, that will be owned by nobody and everybody. There’s so much delicious opportunity to work in that domain because it’s been ignored for so long. One thing we did with our collaborators at Spawning is put out a dataset called “PD40M” of 40 million public domain images—it’s basically all of them, and it’s sufficient to be able to begin training models on.

Because we know what’s in the public domain to a very detailed degree, you can explore this idea of agents sending you out into the world as opposed to keeping you locked into your phone. The Starmirror app, which we’re building, knows what’s in the public domain and knows what is not. It can send you on these little missions or challenges to go and take pictures to fill in the gaps of what it doesn’t know. We’re just setting that up in a very light, easy way, but the implications of it are bigger. What would a decentralized sharing protocol of people who are discovering things on behalf of each other look like? We’re really serious about this idea of people being out in the world and discovering things and then sharing them with each other. How would you coordinate that? It would make sense to coordinate it on-device so that rather than social media, you have AI agents socially mediating people. That protocol seems rich. There’s a lot there that is very different to how people are thinking this is going to go.

QM: Who’s the author of Starmirror? Or is that the wrong question to even ask?

HH: In the traditional music industry, you would have this pop star who would be an avatar for a whole machinery of people. I mean, that still happens. Then with the ubiquitous internet, the idea was that everyone can do everything, but what that really meant was everyone was just isolated and trying to compete with each other, rather than working in the old industrial sense where everyone was getting paid for doing these various jobs. Everyone became a solo agent, and that wasn’t necessarily a good thing.

The AI conversation explodes this lone genius myth, where the medium itself is asking you to rethink your creative role in this hugely collaborative process. We acknowledge that we are much better if we work with people who will have very specific expertise, like Bianca Peruzzi, who’s an amazing lighting designer. We knew we wanted the light in the exhibition to play a really important role so that the room would feel like it was being controlled by another intelligence, and it was fully automated. I don’t know how to program and mix the light, so we worked with Bianca. We don’t micromanage Bianca—we let Bianca come in and be the creative artist that she is, and then the whole show is a thousand times better because of her contribution.

MD: In the 20th century, you had a centralization of media, and the media forms were limited by physical objects. Would you really want to put 60 names on a record cover? So you have to end up compressing it down and say this is the Michael Jackson record. Michael Jackson is incredible, but there were all kinds of people who brought a lot to that. One of my favorites is Rod Temperton, who’s a dude from Blackpool in England who nobody knows, but who was recruited by Quincy Jones to write a lot of Michael Jackson’s music. It’s unbelievable. All these things that we cherish as a society were these products of a funding structure that enabled brilliant people to collaborate. Would that record have been as good had Michael Jackson not been the one performing it or contributing to the writing? No, it would not have. But now we live in a different age where we will soon have models that can help you to digest the complexity of how remarkable cultural things happen.

I think that this positive-sum way of looking at a culture, for one, is the truth. But number two, it’s just so much more interesting.

Quincy Mackay is a freelance culture journalist based in Berlin. He writes about the places where art intersects with politics and history.

Reboot publishes essays by and for technologists. Sign up for more like this:

🌀 microdoses

In local (San Francisco) art news, Altman-Siegel, the gallery representing artists such as Trevor Paglen and Lynn Hershman Leeson, has closed, and that building that looks like a bunch of cootie-catchers off the 101 is being turned into an Eames museum.

Skip the KAWS exhibition at SFMOMA but do stop by their “‘Tis the Season of Kuchar” screening on December 18 for irreverent handheld video cheer.

Check out friend-of-Reboot Lucas Gelfond’s recent sloptimist case for AI aesthetics in Spike.

💝 closing note

Have more AI art takes? Pitch us!

I read this article when it first came out, and realised that Berlin was on my Europe itinerary; now, one month later, I’m writing this comment after the auditory-visual experience that is Starmirror.

(Thanks for the recommendation, Reboot/Quincy!)

Reading the interview added some further depth to my experience of the exhibit. I arrived on a quiet Sunday morning, and found myself in an odd experience where the exhibit was empty. It was like being the first person at Church, and the sermon had already started being preached.

Slowly, surely, then all at once, others filtered in. As the author notes, it was panopticonic - both enjoying one’s own experience, and noticing how others navigated the music and physical space too.

Two thoughts struck me most during this:

1. **It felt like I was in a techno-religion sermon**. I imagined a world where every Sunday, people would come together and collaborate with a model to form some new creative piece. Every aspect of the physical space created this effect: the overhead ceiling light panels that felt like a machine god speaking, the dangling spotlight which created beautiful fractal patterns through the fixtures of the central Hildegardian ladder, and of course, the curated choral music curated intertwined with generative AI output.

2. **I** **felt an acute sense of psychosis**. Between the choral pieces, there were pieces in which the room was flooded with a cacophany of voices, flashes, and sounds. I couldn’t pinpoint which sounds may have come from the people around me - creating this disturbing, eerie episode of “ah, this is what it feels to have your grip on reality loosened”. Beyond this, the lighting veered from highlighting the GPU fans whirring their tunes, to highlighting the central gold engraving of a child. Then, the music changes and the lights direct your attention behind you, to a red door which you’ve never seen before, ominously glowing. It was a surreal experience.

As you can see, the thoughts spurred plenty of thoughts on the future of AI. This physical construction, amidst a digital sea, felt viscerally unique.