This fall, Apple and Google are introducing AI photo editing features into their new phones. Given the (as yet mostly unfulfilled) hype cycles of how “AI will change everything” of the past three years, it may seem like an insignificant milestone. In this essay, Julia Kieserman connects this trend with the broader history of photography, memory, and smartphones, and makes a convincing argument that this, in fact *will* change everything.

— Hal Triedman, Reboot Editorial Board

A Strange Kind of Memory

By Julia B. Kieserman

My childhood dog Louie took his last breaths on the dull gray table of a veterinarian’s office, the grief of the moment cruelly interrupted by a sunny August afternoon peeking through the window. The day remains sharp in my memory against an otherwise blurry picture of lazy August days. On this day, I can tell you what I ate for breakfast, sitting at a diner with Louie while we mentally prepared for what lay ahead. I can tell you that I was wearing a watch, which I kept checking even though we had no scheduled appointment. I can tell you the look of disdain on the waitress’s face when I requested Louie get a full breakfast combo on a real porcelain plate, placed on the ground in front of his nose.

What I can’t tell you is why, as we stood in the vet’s office stroking Louie’s paw and whispering into his velvety ears, I slipped my iPhone out of the back right pocket of my jean shorts and unceremoniously took his photo. My mother hadn’t noticed, but Apple had. Not long after, I got a push notification and was face to face with the photo, thrust back into the memory of that day but no longer on my terms and not for the last time.

Over the last eight years, phone companies have co-opted the word “memory” to include algorithmically selected versions of our photo collections served on their timelines. This past summer they’ve expanded memory features to allow photo editing and manipulation in service of portraying a particularly desirable narrative. These features are making a bold claim: photos encapsulate memory and memory is ours for the shaping (with the help of a pricey Apple or Google phone, of course). But are they right?

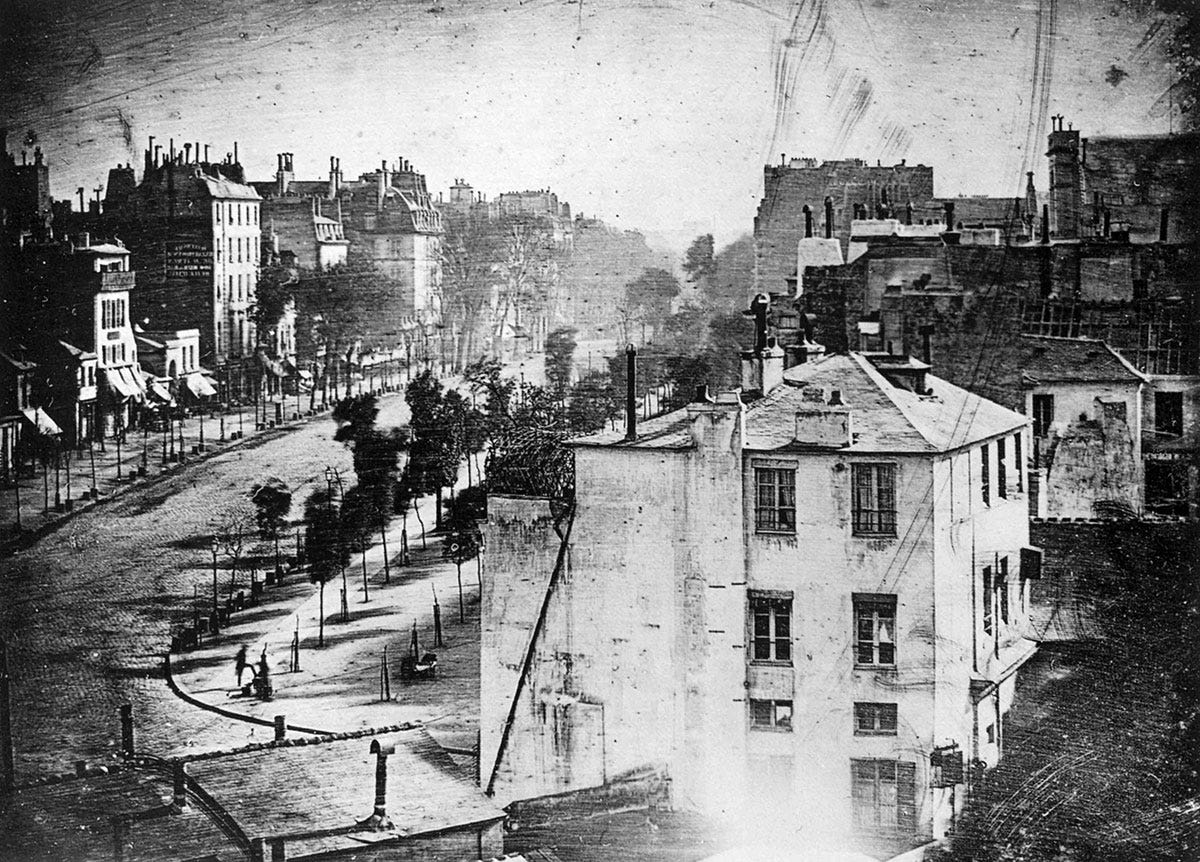

The first known photo of a person was taken in 1838 by a French engineer, Louis Daguerre, credited with the invention of photography. It captures a blurry figure getting their shoe polished on an otherwise silent street in Paris. Except, it wasn’t a silent street at all. The photo, taken over the course of five minutes, was only able to capture the lone figure on a bustling street that remained still during the entire exposure period. Although there isn’t much about an iPhone that resembles the equipment of a 19th century camera, the spirit of the underlying technology remains the same. Even if photos can now capture someone that won’t stand still for an entire five minutes, they cannot possibly capture the full context and nuance of the scene unfolding in front of them. To some extent, this makes sense—photos are simply the output of a technology tool. A photo is taken by a person with an end goal, whether that is showcasing their perspective (Ansel Adams), advancing a political narrative (Stalin’s Great Purge), or unearthing injustice (Nick Ut’s photo of Phan Thị Kim Phúc, or Napalm Girl, during the Vietnam War). This is even true for the photos that we take over the course of our days and weeks, often motivated by an end goal more intangible and personal.

My end goal, when taking a photo of Louie’s last breaths, was an attempt to do something in response to a significant moment or, as Susan Sontag argues, “not just the result of an encounter between an event and a photographer; [but] an event in itself.” This photo was as much about my experience with death as it was about my dying subject. Although that may not be true for every photo, it is always true that a photograph alone isn’t the full picture. That is, until the image of Louie’s face nestled into my photo library and Apple redefined its reason for its existence.

Apple introduced “Memories” in 2016, with the release of iOS 10. Memories, or what we shall henceforth call Memories™ to distinguish them from the old fashioned memories of the brain, is a Photo application feature that can “surface memories that’ll be most relevant to you in any given moment.” A bold claim and something even my own brain doesn’t seem to get quite right. Memories™ uses a combination of neural networks and clustering techniques to build up a knowledge graph and identify places, people or—as of its first update after launch—pets in your photo library. For example, the Photos application will try to correctly identify a person by detecting and analyzing faces and upper bodies and compare them to known photos. They also rely on other context cues like clothing, especially in instances where multiple photos of the same scene are taken but the lighting or angle of someone’s face varies. This data is used alongside other pattern behavior data, like detecting the last time a photo was taken with a specific person featured or how frequently a place is visited, to create compelling Memories™ based on a theme and photo set.

Unsurprisingly, this clustering can go wrong in myriad ways. In one example, Apple presumed my brother and I were a couple after analyzing photos from a few adult sibling trips, creating an “Early Moments Together” Memory™ of the two of us. In a more heartbreaking example, one reddit user was shown a Memory™ with photos of their brother right after he died. Apple addressed this particular concern with a feature that allows you to mark a person to be featured less or not at all if you so choose, but it dances around the more substantial question: Can a Memory™, that is, a collection of photos, really play the role of a memory? And how do these photos pay tribute to, or even deviate from, our memories in the first place?

My memories of Louie are triggered by seeing a dog on the street with a stump for a tail and a defiant attitude. When my mind turns to him, it remembers both the pleasure of watching TV on the couch together and the frustration of convincing him to walk in the rain. But sometimes something else prompts his memory—a push notification from Apple. One such Memory™, titled “Pet Friends,” cycles through Apple’s selection of Louie photos incongruously set against Jeff Babko’s bluesy jazz. Every photo was washed in “warm contrast”, one of a handful of different look options that also includes fade and noir film. Some of the photos, including a young Louie ferociously clutching a favorite toy, line up perfectly with my memory of him. Others felt inauthentic, including the photo from his last few minutes of life.

That photo captures gaunt cheeks, a dry tongue, and glazed eyes, a far cry from the mischievous, food-motivated methane producer that I loved. When my iPhone displays a 13-year old bulldog on the brink, I recall a warrior and an old friend ready to get some rest. But as years pass and I continue to look at the same algorithmically selected photos of Louie again and again, the unselected ones start to fade. His image becomes warmer in contrast, his presence more bluesy jazz-like. The more I see his haggard face, the more I start to wonder if I do in fact remember him as the face that lives in my Memory™.

Although Apple isn’t strictly in the business of memory-making, it certainly benefits from our photo collections. Consider that Apple can create up to three memories a day and generate a push notification for each. Or recall that Apple’s iCloud storage, its most popular service, charges users monthly fees to store data beyond 5GB. According to one estimation, iCloud will earn $11.5 billion in revenues next year, a significant portion of which is certainly photos and videos. More photos require more space that Apple (or Google) is happy to sell.

In fact, photo taking, editing, and storage have been a primary focus of phones for quite some time. Every new iPhone model since the initial launch in 2007 has included a camera improvement, effectively eliminating the need for a separate camera for anyone that identifies as even a notch below amateur photographer. This is a nice feature, but it’s notable that Apple gives the camera preferential treatment over other functionalities. For example, iPhones allow the use of the camera app without authentication, one of only three features with unprotected access (the other two, a flashlight and emergency calling, are clearly in service of more practical needs). If the goal is to keep us taking photos and minimize deletion, continuing to find ways to generate a perceived value from photos, like packaging them up as memories, is an excellent way to do it.

This isn’t to say that photos never deserve prioritization or don’t have a genuine role to play in the art of remembrance. Photos can capture the bits and pieces of life that are so honestly human as to be completely ordinary. New York Times culture editor Melissa Kirsch describes snapping photos of her apartment as “not photos I want to look at now, but 20 years from now when I’ve forgotten about these details that are mundane but so essential to my daily life.” But we don’t really need to preserve all of those small details. Our brains can’t store every observation, thought or perception that passes through and that isn’t a bad thing. Constraints and selections are what allow us to stay sane in a world of complete sensory overload.

Even if we wanted to store every photo, our environment does not have unlimited capacity to do so. Both Apple and Google make this easy to forget, natively integrating cloud services with hardware, allowing for what can feel like an infinite amount of storage space by offloading data from a device to the cloud. Even the language “cloud storage” evokes images of limitless white fluff dancing across a beautiful summer afternoon sky. But of course, photos don’t really live in a cloud, they live on servers in warehouses in Ohio, Virginia, Cape Town, and Osaka. They rest in hundreds of thousands of square feet lit by a faint blue glow that lives at the aesthetic intersection of an eighties era office building and The Matrix, keeping scores of machines cool, alive, and quietly humming. They are an overwhelmingly real physical use of resources.

My photo of a since discarded shirt and a blurry rabbit I ran into on the streets of Boston both reside indefinitely in one (or several) of these complexes, although where I’ll never know. Data centers account for an estimated 4% of global energy use and 1% of total greenhouse gas emissions. This consumption isn’t going away. In fact, Google reported that their emissions grew 48% over the past five years, a good chunk of which was attributed to an investment in artificial intelligence infrastructure. As the alarm bell of global catastrophe continues to ring against largely deaf ears, we should ask ourselves: is it really worth keeping all of these photos? But before we’ve even had a chance to answer, Google and Apple have found a new and much more consequential purpose for the nearly 5 billion photos taken every day.

With the advent of photo generation models, Google and Apple phones are steering us from a world of curated memories to a world of malleable ones. This summer, Google’s Pixel 9 phone updated their suite of “magic” photo editing tools, transforming photos into something more akin to a canvas, ripe for modification and reinterpretation. Magic editing can remove pesky background details, like a piece of litter or an annoying ex, or modify the color of a sky, turning a “gloomy horizon into a colorful sunset.” This is done through a technique called inpainting, which borrows pixels from the surrounding region to understand how to fill in visual gaps. With an increasingly sophisticated semantic understanding of an image rather than a pixel level understanding (the difference between detecting a blue dot and detecting a beach scene), tools become more effective at modifying images in nuanced ways.

With these tools, AI edited photos can reflect the reality you wanted to have experienced, rather than the reality as you actually experienced it. In essence, you are no longer capturing moments but generating them, creating an entirely new visual artifact that contains a completely artificial component. These editing tools could appropriately be marketed as belonging to a suite of art or graphics capabilities rather than photos. For example, if your visit to a scenic overpass was ruined by a short bloom season, you can use the Reimagine feature to type “wildflowers” into a text prompt and simply add them into the scene, hiding the impact of global warming. If your child refuses to join a family photo, artificial “magic” can add them in from a different image, and the challenge of successfully navigating child-parent relationships is erased from the digital record. Or, if your dream of surfing with your beloved bulldog was ruined by his deep-seated fear of water, you could create a convincing shot of the two of you riding a wave together.

Apple’s iOS 18, released last week, has similar features that rely on “Apple Intelligence”. Users can now take an image that “wasn’t quite perfect” and identify the distractions “so you can make them disappear.” It also turns Memories™ into a storytelling exercise. Rather than passively receiving a Memory™ from our phones, we become conductors, typing in a prompt that Apple then uses as a guide to select photos and music to “create a memory about the story you want to see”. This does mirror the behavior of our brain to some extent. Nobel-prize winning behavioral psychologist Daniel Kahneman describes us as having two different selves: the experiencing self and the remembering self. Essentially, the person we are during an experience is not the person we are when we attempt to remember that experience. The consequence is that “what we get to keep from our experiences is a story.” However, now it isn’t the unique and individual story our brain has latched on to as a part of an innate and intricate survival mechanism. Instead, it is a story of averages, an engineering model’s best guess at what is likely to come next based on millions of stories it has seen before.

Although Apple and Google largely describe these features in the context of personal use, it is the same underlying technology that can be used to create the fake imagery that has recently proliferated online spaces. Instead of adding a photo of my dog on a surfboard, I could source a photo of a stranger I took without permission or of a celebrity I found online. I could substitute the ocean for a famous train station and a surfboard for a bomb, and this quickly becomes nefarious. We may now know enough to fear the forms of misinformation we fall prey to when others disseminate modified images to serve their own interests, but there are more subtle forms of abuse too, like manipulating family photos and showing them to an aging relative who no longer can clearly distinguish between known and unknown faces.

As Surrealist artist Salvador Dali said, “the difference between false memories and true ones is the same as for jewels: It is always the false ones that look the most real, the most brilliant.” What type of trickery might we be playing against ourselves with the use of these tools to modify or enhance our own images? How many times do I need to see a photo of Louie surfing with Jack Johnson playing in the background to forget that he was afraid of water and believe that it may have happened?

It was obvious to any Parisian taking in that first human image of a nearly empty Boulevard du Temple that the photo was incomplete. But as technology has improved, the colloquial understanding of photo as a form of expression has been replaced by photo as truth. As AI photo editing becomes commonplace, we are given an opportunity to re-introduce a skepticism that perhaps should have always been present. Photography, like artificial intelligence, is just a technological tool. The photograph, like the diffusion model output, will always be a manipulated and curated version of reality, filtered through the eyes of its creator under the constraints that govern its existence.

When I recount my memories of the day of Louie’s death to my mother, she swears that the waitress that served him was not full of disdain, but full of sympathy. When I mention that Louie perked up at the smell of bacon, she gives me a look of disdain: what decent Jewish mother would feed her beloved furry son pork? My mother and I spent that entire day together and, although in broad strokes we lived the same story, most of the details we remember are entirely different. This is a feature of memory—a unique manipulation and curation process to impose order on a world of sensory perceptions and emotional experiences that are so chaotic as to be overwhelming. In the words of Joan Didion, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live”—and those stories become the lenses that distort and color our remembrances.

As AI photo editing becomes massively available, this feature is co-opted by technology companies. It becomes clear that we have long played the role of both magician and audience. The magician, understanding—and now creating—the illusions present in the images we see and the audience, tricked into believing them anyway. When writing and re-writing the narratives that shape our lives, we need to quiet our delightfully fooled inner audience member and prioritize our inner magician, who knows what is hidden behind the curtain.

— Julia B. Kieserman is a writer and PhD student in usable security. She likes hanging around books and bulldogs.

🌀 microdoses

Seriously, if you aren’t convinced about the importance of this moment by Julia’s amazing writing, read these two pieces about how massively-available AI photo editing is a big deal:

“No one’s ready for this,” by Sarah Jeong in The Verge

“For Google’s Pixel Camera Team, It’s All About the Memories,” by Julian Chokkattu in Wired

A cross-lingual history of the Wikipedia lead photo for the article “Sandwich”

Turns out one guy named Gage Skidmore is responsible for (at present) 104,751 photos on Wikimedia Commons, including many of the bad photos of hundreds of celebrities at San Diego Comic Con that are the only available commons-licensed photos of those people for use on Wikipedia? Just went down a whole rabbit hole on this, the internet is a strange and fun place.

💝 closing note

Please please pitch us, or send us a letter to the editor! Our new editorial board is eager to see what you’re thinking about (especially if you’re not a ~professional writer~), and we love to hear from our readers. And if you have a longer piece, or something more creatively inclined (visual art, internet art, poetry, etc.) keep your eyes out for details about some big projects coming in the next few months👀👀👀

— Hal & Reboot team

this is just an important line: "Constraints and selections are what allow us to stay sane in a world of complete sensory overload.". thank you for the reminder. 'constraints and boundaries' are underrated. hence point #8 of "LE NEW CONSUMER" manifesto: https://objet.cc/manifesto