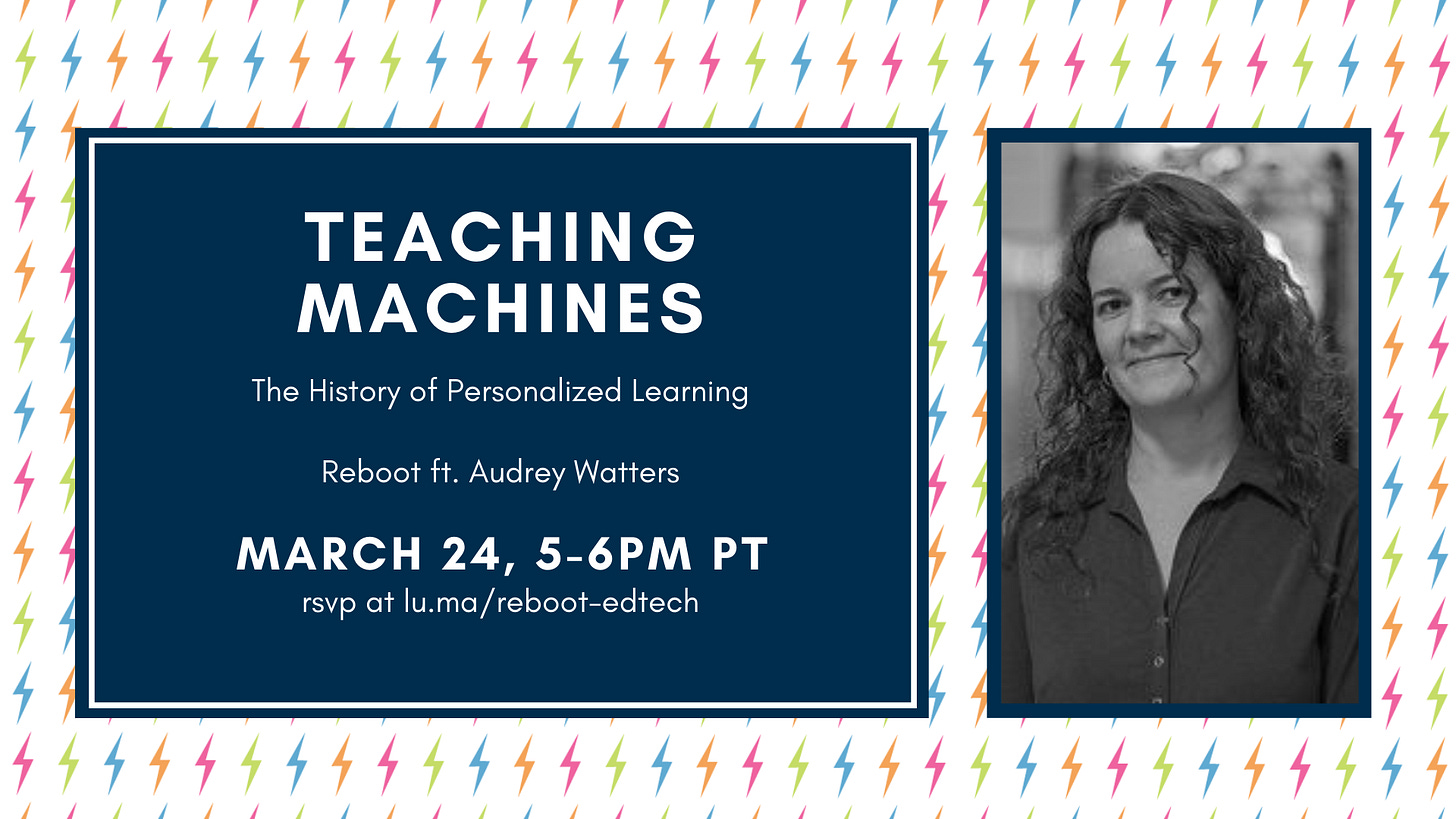

⚡️ New Event: Teaching Machines ft. Audrey Watters

What is the purpose of education, and how can educational tools be designed to meet those purposes?

As a community comprised of many students (and recent students), we’ve thought a lot about teaching and education, which is why I’m really excited for our next event:

📖 teaching machines by audrey watters

Our guest for this Thursday, March 24 is Audrey Watters, a writer on education and technology. She is the creator of the popular blog Hack Education and the author of widely read annual reviews of educational technology news and products. Teaching Machines is a thorough yet accessible history of personalized learning, and the ways in which technology has been supporting (or failing to support) educational goals.

Join us next Thursday for a Q&A on the long-held dream of using technology to automate teaching, and what this history means for us today.

🏫 our take: it’s not about khan academy

By Anh Pham and Pearl Zhang

Having been a fan of Khan Academy for quite some time, I remember feeling fascinated by an eleven-minute video, in which Sal Khan and Forbes’s Michael Noer summarized the history of the US’s current education system and Khan Academy itself. Skipping from the 1890s to the 1990s, Khan narrated, “education is static to the present day”—that is, until the emergence of the computer and the internet. For the first time in history, as they told it, learning was personalized.

To be fair, the video is short, and its purpose is not about giving a lengthy history lesson. But that skip in the narrative (or “the sweep of time”, as Khan says) seems to mirror a common misconception among many of us about the actual history of personalized learning. It didn’t start from the dot com bubble, Khan Academy, or any other hot, new Silicon Valley edtech startups. Audrey Watters’s Teaching Machines: The History of Personalized Learning is a wonderful attempt to retell the right history.

According to Collins Dictionary,

teaching machine (n): a machine that presents information and questions to the users, registers the answers, and indicates whether these are correct or acceptable.

The goal behind these teaching machines was best explained by popular psychologist and behaviorist B.F. Skinner, who believed the traditional classrooms had disadvantages since different students might have different paces of learning. He also supported operant conditioning (a type of learning process where a behavior is responded to with reward or punishment) as a solution to the problem of delayed reinforcement due to the lack of individual attention. Thus, with the help of a machine, a teacher can focus on their actual teaching and students can thrive at their own pace.

In Teaching Machines, Audrey Watters recounts the long history of such an idea maturing, from Sidney Pressey’s mechanized test-giver in the mid-1920s to Skinner’s teaching machine in the 1950s. These psychologists’ theories were influential, but their devices never made it into widespread use. Watters also illuminates similar works by other twentieth-century education technologists, psychologists, publishers and reformers. Some of those actually succeeded in marketing their devices, like Norman Crowder and the AutoTutor; some of them were unsung heroes, like Susan Meyer, who wrote the first program for the machines and worked directly with schools.

Watters particularly challenges what she calls “the teleology of edtech”—the idea that technological progress is the pinnacle of edtech. Too often, the context is stripped from the stories written about edtech, and all that seems to matter is the technology itself. Teaching Machines isn’t just a story about machines. It’s also a story about people, politics, systems, markets and culture. From the launch of the Sputnik satellite and the propagation of American exceptionalism to the youth led civil rights movements of the 1960s, Watters spotlights programmed instruction and personalized learning in all of their complex and nuanced forms. As much as the edtech startups might like to imagine an alternative future separate from the past, it is still the very same ideas from decades ago that continue to dominate the current thinking about technology in education.

Above all, there is a key question: what is the purpose of education, and how can educational tools be designed to meet those purposes? Sal Khan’s narrative of edtech history skims past the messy parts of political systems and capitalist culture; he emphasizes the purpose of education as beginning and ending with technology, and the ability to create a shinier future. In contrast to Khan’s pitch of edtech history, Teaching Machines’ historical narrative lingers in the past. While Watters hints at the present, I would’ve enjoyed seeing a more in-depth analysis of edtech history applied to the current landscape of edtech. However, I appreciate the ambiguity Watters leaves for further exploration in her retelling of edtech history.

One such example of this nuance occurs in Watters’ critique of Khan's quick fix solution in her writing of the Freedom Schools and Freedom Vote Campaign in 1964. Instructional programming was a critical component in their success yet also a focal point of tension, specifically in the tension between a radical education of activism rooted in defiance and joy versus the methodical programmed instruction designed to condition pupils to conform.

Watters highlights Paulo Freire’s pedagogy of problem posing education, “a dialogue with students and teachers where knowledge is jointly constructed”, in the Freedom Schools: teachers and Black students worked alongside each other to build educational materials that increased Black voter turnout and adult literacy. The intentional dialogue between teachers and students is rooted in humility and invites readers to critically reflect on the ways doing things that don’t scale might be more mutually beneficial and successful as opposed to engineering more methodologies for programmed instruction.

Teaching Machines is for anyone who wants to learn the detailed history behind the United States’s modern education technology sector. The accessible narration makes it easy to follow through the historical events highlighted for each chapter, most notably B.F. Skinner’s futile journey of bringing his teaching machine to market, with a few witty snarks sneaked in between. However, there seems to be a hyper-focus on many minute details of Skinner’s business attempts and his lengthy personal correspondence (especially in the middle chapters) that sometimes detracts from the central idea. The conclusion is phenomenal, though readers might finish with more questions than answers. How does the past inform the future? What now? What can we do next?

Seeing how the present mirrors the past is striking. Within school environments, educators and technology developers generally hold more power than students; it will require intentional dialogue and humility on their part to seek out and practice problem posing education with their students.

Yet an ethos of hope can be glimpsed throughout; for example, the Freedom Schools optimized for students’ wholeness and self actualization with thoughtful humility. Intellectual growth must encompass new pathways through which individuals and communities can assert agency over their own learning. These pathways are less orderly than technology’s clean-cut solutions, but perhaps, it is by pressing into the uncertainty and ambiguity where genuine learning happens.

Pearl Zhang is a junior at Swarthmore College studying computer science and education. In her free time she enjoys reading fiction and memoirs and exploring hole in the wall restaurants.

Anh Pham is a software engineer based in Vancouver, Canada, currently working at Mastercard. She loves consuming queer content, Kpop, kicking asses with Taekwondo and petting corgis!

🌀 microdoses

Some folks from Bernie’s campaign are apparently encouraging Ro Khanna, author of a new book on tech & equity, to run for president if Biden doesn’t seek a second term.

“Prince of Crypto” is a weird title, but still worth reading this profile of Vitalik Buterin in TIME

Is it too early to start dropping hints that we’ll be hosting Ben for a book talk in a few months?

We do not have a token

You hate to see it

💝 closing note

Today I am too tired to put together a creative closing note, so all I’ll say is …. hope to see you all next week!!!!

Reboot team